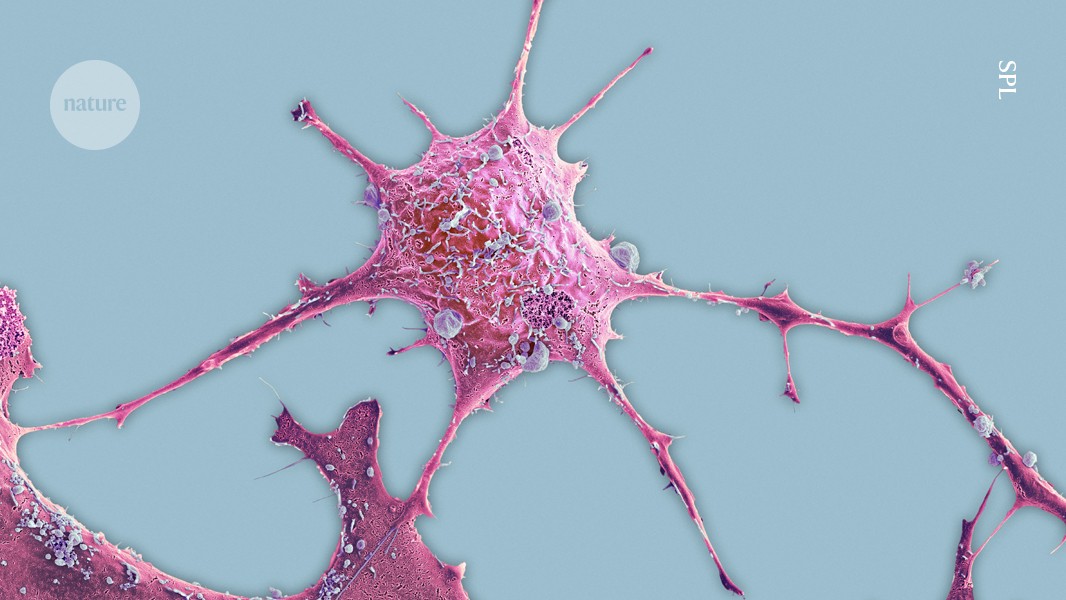

Breast cancer cells (artificially coloured) are more likely to spread from tumours that include more nerve fibres than from those with fewer such fibres.Credit: SPL

The sorts of nerve that allow people to touch, see, hear and taste can help breast cancer cells to infiltrate other regions of the body, suggests a study1 in mice and laboratory-grown cells. The research also shows that a drug used to treat nausea can block interactions between some cancer and nerve cells.

Further research is needed to confirm that the results hold true for people with breast cancer. But the paper, published today in Nature, is the latest in a wave of discoveries about the relationship between cancer and the nervous system. The finding is unique, however, in that these ‘sensory’ nerves seem to be interacting directly with tumours to aid the cancer’s spread, rather than triggering immune responses that then encourage tumour formation and growth.

The focus on sensory nerves, as opposed to other branches of the nervous system, is particularly notable, says Timothy Wang, a gastroenterologist at Columbia University in New York City, who was not involved in the study. “These nerve fibres are very abundant and always sensing,” he says. “I am coming to think that the sensory nervous system is probably going to be among the most important overall in mediating the growth of solid tumours.”

Nerve cell–cancer crosstalk

The study began when Sohail Tavazoie, an oncologist and cancer biologist at The Rockefeller University in New York City, and his colleagues were looking for genes that drive the spread of cancer in the body. The search kept turning up genes involved in the nervous system, and Tavazoie’s team began to wonder whether the nervous system and cancer cells communicate to promote cancer metastasis.

Cancer cells have ‘unsettling’ ability to hijack the brain’s nerves

To find out, the researchers looked at the presence of proteins produced by nerves in breast tumours. They found that the cancers that had more nerves were more likely to become invasive than those with fewer nerves.

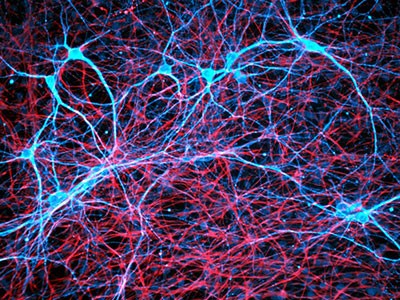

Then, Veena Padmanaban, a cancer researcher also at The Rockefeller University, developed a method for growing mouse mammary-cancer cells and sensory neurons in the same tissue-culture dish. The team found that the presence of cancer cells stimulated the nerves in these cultures to produce a natural molecule called substance P, which is involved in responses to pain and inflammation, among other processes.

A formula for tumour growth

The researchers followed up by examining human breast cancer samples and found that tumours with high levels of substance P were more likely to have spread to the lymph nodes.

Tavazoie and his colleagues suggest that substance P sets off a molecular chain reaction that activates genes associated with metastasis. The authors propose a way to shut down this cascade using an anti-nausea medication that is already given to some people with cancer when they receive chemotherapy. The team found that the drug, called aprepitant, slowed tumour growth in mice and reduced signs of invasive potential in cancer cells grown in cultures with sensory nerves.

Aprepitant is usually given for only a few days at a time, but the findings suggest that clinical trials in which people with cancer receive the drug for a longer period could be warranted, Tavazoie says.

Repurposed drugs

It remains to be seen how well these results will translate from the lab to the clinic, and from breast cancer to other tumour types, he adds. But previous studies have found that nerves of the autonomic nervous system, which regulates involuntary organ functions such as heart rate and digestion, can contribute to prostate and gastrointestinal cancers2,3.

And clinical trials are currently testing findings4 by Erica Sloan, a cancer biologist at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, and other scientists, that showed that a branch of the autonomic nervous system influences breast cancer. Those findings suggested that drugs called beta blockers, currently used to treat some cardiovascular diseases, might reduce the chance of metastasis.

Current clinical trials are testing beta blockers in combination with other cancer treatments, including immunotherapy and radiation, Sloan says. “This drug-repurposing space has opened up,” she says. “It’s going to be important to see how relevant this is in a clinical setting.”