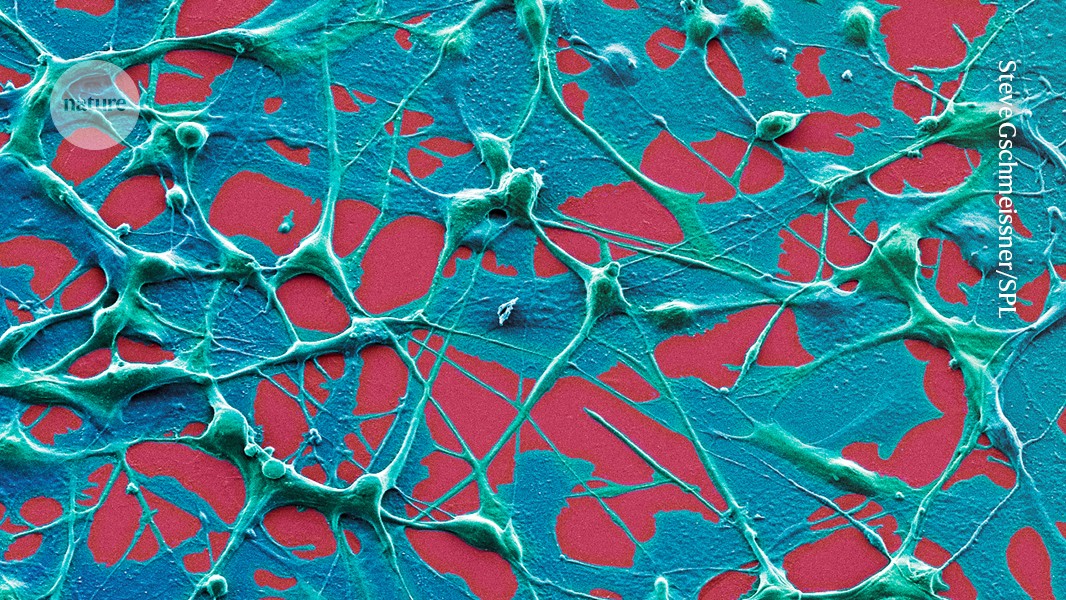

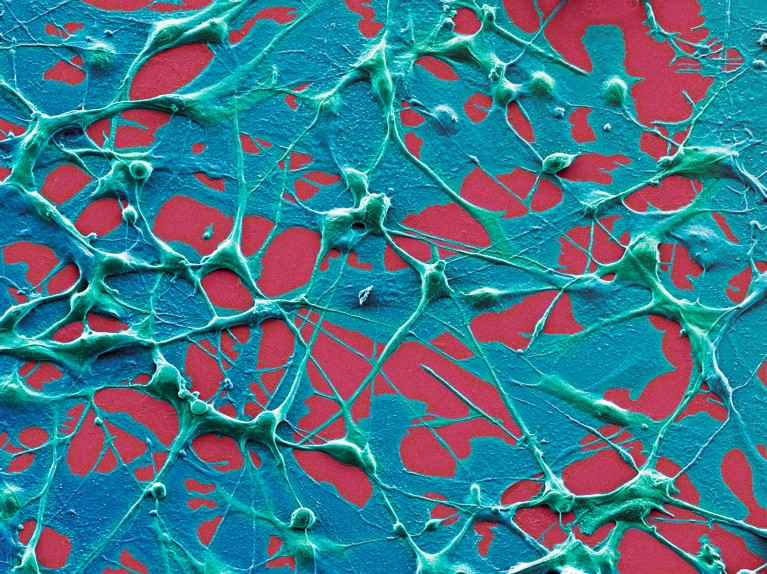

Melanoma cells (artificially coloured). An immune-based therapy was more effective against this cancer in people who received an mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine within 100 days of the start of their cancer treatment.Credit: Steve Gschmeissner/SPL

A vaccine that helps to fight cancer might already exist. People being treated for certain deadly cancers lived longer if they had received an mRNA-based vaccine against COVID-19 than if they hadn’t, finds an analysis of medical records.

Follow-up experiments in mice show that the vaccines have this apparent life-extending effect not because they protect against COVID-19 but because they rev up the body’s immune system1. That response increases the effectiveness of therapies called checkpoint inhibitors, the animal data suggest.

“The COVID-19 mRNA vaccine acts like a siren and activates the immune system throughout the entire body”, including inside the tumour, where it “starts programming a response to kill the cancer”, says Adam Grippin, a radiation oncologist at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, an co-author of the report published today in Nature. “We were amazed at the results in our patients.”

The findings, which Grippin and his colleagues hope to validate in a clinical trial, suggest further hidden capabilities of mRNA vaccines, even as the administration of US President Donald Trump has slashed about US$500 million in funding for research investigating the technology.

Working in tandem

Checkpoint inhibitors unleash the immune system to attack cancer cells. They have transformed the treatment of many cancers, but they fail in more than half of the people who receive them: some recipients’ immune systems remain too sluggish to attack cancer cells.

To address this gap, researchers have been developing personalized ‘cancer vaccines’. These would be used in tandem with checkpoint inhibitors to help an individual’s immune system to target the unique mutations found in their cancer cells. Although early results are promising, these treatments are still experimental and, once available, will probably be very expensive and difficult to access.

Infographic: How does a cancer vaccine work?

Grippin and his colleagues wondered whether the general immune boost that mRNA vaccines create could be enough to wake up the immune system. They found support for this theory in mice2, leading them to investigate whether the effect would carry over into people.

The researchers analysed the medical records of more than 1,000 people with lung cancer or melanoma. They found that, in people with a certain type of lung cancer, receiving an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine was linked to a near doubling in survival time, from 21 months to 37 months. Unvaccinated people with metastatic melanoma survived an average of 27 months; by the time data collection ended, vaccinated people had survived so long that the researchers couldn’t calculate an average survival time. People whose tumours had traits hinting that they were unlikely to respond to checkpoint inhibitors saw the biggest survival boost after vaccination.

This finding is “quite impressive”, says Benoit Van den Eynde, a tumour immunologist at the University of Oxford, UK. “I did not expect the effect to be that significant, and the data are very strong.”

Window of opportunity

Timing matters: those who had received the jab within 100 days of starting treatment were more likely to benefit than were those who received it outside that window. Grippin has collected data, which are yet to be published, suggesting that receiving the vaccine within a 30-day window before or after treatment could elicit an even stronger boost, he says.