The work of COP30 president André Corrêa do Lago and Brazil’s environment minister Marina Silva must continue at COP31 in Antalya, Turkey.Credit: Pablo Porciuncula/AFP/Getty

The 30th United Nations climate conference, COP30, ended on Saturday evening with an agreement between the 195 participating nations. The United States, which pulled out of the 2015 Paris climate agreement at the start of the year, did not send a delegation. This no-show of the world’s second-largest carbon emitter was not the only disappointment. The meeting, which was held in Belém, Brazil, has done little to make progress, with the decisions made and the eight-page final document barely shifting the dial on slowing down climate change or averting its most dangerous effects.

Don’t scrap climate COPs, reform them

There were some positives. Delegates to this conference of the parties (COP) agreed on a substantial increase for ‘adaptation finance’, whereby high-income nations fund projects, ideally through grants, that protect low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) from the effects of climate change. But although COP30 was dubbed the ‘implementation COP’, the core issue of phasing out fossil-fuel use did not make it into the final text. Even by the incremental standards of COP meetings, things have stood still.

In 2021, governments attending COP26 in Glasgow, UK, agreed to “phase down” the use of coal without carbon capture and to eliminate subsidies for fossil-fuel companies. They then adopted a goal of “transitioning away from fossil fuels” at COP28 in Dubai. But despite the efforts of a coalition of at least 80 countries from around the world, negotiators at COP30 failed to agree on even the idea that this transition needs a road map. This failure was mainly the result of opposition from oil-producing states, led by Saudi Arabia and including influential countries such as India and Russia — known collectively as the like-minded group.

Next year’s COP will be held in Antalya, Turkey, and will be jointly organized by the governments of Australia and Turkey. The two hosts and their allies have 12 months to inject some fresh thinking into a stalling process that risks consigning current and future generations to the perils and uncertainties of a warming planet. Fossil fuels must be phased out in a just and equitable way if the world is to prevent dangerous climate change. The challenge is how to bring the discussion on a road map back to COP31 and avoid a repeat of the outcome of COP30.

The ‘implementation COP’: why the Belém summit must ratchet up climate action

Although Brazil did not succeed this time — nor in agreeing a separate plan that sought to end deforestation — the country aims to continue informally discussing road maps for both goals with those nations that have supported developing such plans. This is positive and echoes a call made in these pages last month for the creation of informal spaces for policymakers and scientists to discuss contentious issues in UN negotiations (Nature 646, 1025–1026; 2025).

However, an agreement on how to end fossil-fuel use isn’t going to happen for as long as the current stand-off continues. Those countries objecting to even the idea of discussing a road map say that they cannot put their economies at risk. This is a legitimate concern, and any discussion on a road map must engage, in the necessary detail, with how to mitigate this.

However, national interests will not be served unless all countries can be persuaded to recognize the enormity of the bigger picture. That’s a core lesson from the 2015 Paris climate agreement, and from accords in other domains that have succeeded against the odds, including this year’s agreement on a pandemic treaty. These have succeeded, at least in part, because countries rich and poor realized (or accepted) that if they did not act together, there would be risks for everyone — including themselves.

Navigating the black box of fair emissions targets

The transition to renewable energy is under way, especially in LMICs. But the development of clean energy is not going to reduce the risk of dangerous climate change while nations continue to burn fossil fuels at a high rate. This is widely accepted and backed by robust evidence. It also cannot be denied that, if climate change is allowed to continue at the current pace, no country will be immune to or safe from its effects. Yes, richer countries will initially cope better than poorer ones. But without coordinated global action, the effects of extreme weather will eventually harm all countries. It is not enough to say this just once or twice. It needs to be repeated again and again.

The legitimate concerns of states that rely on fossil-fuel exports need to be taken into account, and any formula for phasing out fossil fuels needs to be fair and equitable, especially to countries that are still on a path to industrialization. Those least able to afford the transition to clean energy must be supported by those that can. But, in the end, it is in everyone’s interests that all countries act to phase out fossil fuels. Efforts to block even a discussion on this have to stop.

For real climate action, empower women

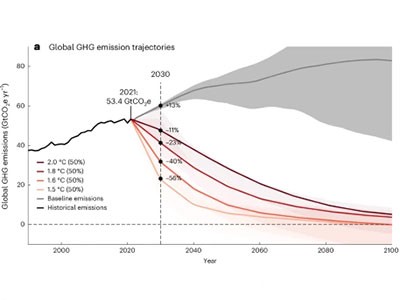

COP30’s failure to acknowledge the need for a road map was a missed opportunity, but the fact that the talks did not blow up completely is a cause for hope, particularly at a time when multilateralism is under severe stress. It is also a sign that countries could yet recapture the spirit of Paris in 2015, when it seemed that the world had finally woken up to the dangers of global warming, and agreed the beginnings of a road map on how to restrict global temperature increases to within 2 °C of pre-industrial levels — and ideally 1.5 °C.

Thirty years after the first COP meeting took place in Berlin, and one decade on from Paris, that road map must be expanded to include a plan to phase out fossil fuels. Failure to do so will leave none of us unscathed.