Chatbot-driven lab robots are automating methods like protein synthesis.Credit: Du Yu/Xinhua via Alamy

Last year, synthetic biologist Meagan Olsen performed the biggest experimental campaign of her career.

The PhD student at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, was trying to make proteins in a test tube more efficiently. Across more than 40 experiments over 4 months, she tested 1,231 combinations of sugars, amino acids and other ingredients, including cellular machinery, before landing on a cocktail that was at least six-times cheaper than existing cell-free protein synthesis recipes1.

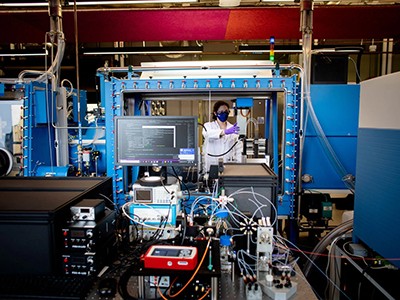

Now, an ‘autonomous laboratory’ system made up of a large language model (LLM) ‘scientist’, lab robotics that automate simple tasks such as liquid transfer and human overseers created by scientists at artificial-intelligence firm OpenAI in San Francisco, California, and Ginkgo Bioworks, a biotechnology company in Cambridge, Massachusetts, has eclipsed Olsen’s record. It achieved a further 40% reduction in cost, after testing more than 30,000 experimental conditions over 6 months2.

The findings — described in a paper posted on the bioRxiv preprint server on 5 February — have sparked discussion over the extent to which chatbot-controlled robots could replace humans.

‘Set it and forget it’: automated lab uses AI and robotics to improve proteins

“That is going to be the future of biology,” says Philip Romero, a protein engineer at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

However, the technology has some way to go before it can gain wide usage. Existing lab robotics still struggle to perform tasks that require dexterous skills or conduct bespoke experiments, such as those involving tissue samples or animals. And achieving some complex research goals, is beyond the grasp of existing AI tools. But, even as autonomous-lab systems grow more capable, scientists stress that human expertise will continue to be an essential ingredient for research.

Self-driving labs

Most efforts to apply autonomous labs to biology have focused on engineering proteins. Romero’s team, for instance, paired a simple machine-learning model with liquid-handling lab robotics to improve a protein’s heat tolerance3. Others have used more sophisticated ‘protein language models’ to predict amino acid changes — implemented by lab robotics — that can enhance an enzyme’s activity4.

Cell-free protein synthesis — in which various combinations of chemicals are mixed with a bacterial cell lysate containing protein-making machinery and a protein-encoding DNA sequence — seemed like a suitable challenge for cutting-edge LLMs such as OpenAI’s GPT-5 that have excelled in mathematics, computer coding and theoretical physics, says Joy Jiao, who is the life sciences research lead at OpenAI. “We really wanted to benchmark GPT-5’s performance in real biology.”

Self-driving laboratories, advanced immunotherapies and five more technologies to watch in 2025

The Ginkgo-OpenAI set-up used GPT-5 to interpret results and design experiments that could be performed by Ginkgo’s lab robotics. The researchers supplied reagents and implemented GPT-5’s experimental designs. They also made protocol tweaks and, after three experimental rounds, gave GPT-5 access to a preprint paper describing Olson’s work, as well as the ability to access other literature on the Internet. GPT-5 kept a lab notebook of data interpretations and hypotheses.

Before the model had access to the Internet or Olsen’s preprint, one of its notebook entries hypothesized a cost-saving reagent swap that Olsen’s team also used. “The model actually had pretty decent biochemical reasoning capabilities,” says Jiao.

Nonetheless, the biggest improvements to the efficiency of protein synthesis came from the experimental steps after GPT-5 had access to fresh information. “All of that allowed it to make a big leap forward and actually beat the human state of the art,” Jiao adds.

Limited dexterity

Michael Jewett, a synthetic biologist at Stanford University in California, who supervised Olsen’s effort, says the Ginkgo–OpenAI recipe for cell-free protein synthesis is broadly similar to the one he, Olsen and their colleagues came up with. However, it’s difficult to know how much of his lab’s work helped GPT-5 to design its experiments.