The first recorded example of Alzheimer’s disease involved Auguste Deter, a woman who died in Frankfurt, Germany, in April 1906, after experiencing memory loss and great anguish.

In physician Alois Alzheimer’s 1907 paper1 describing Deter’s symptoms, he wrote that she “is completely delirious, drags around her bedding, calls her husband and daughter and seems to suffer from auditory hallucinations. Often she screamed for many hours”. Alzheimer examined her brain under a microscope after her death, and described what are now considered the hallmarks of the disease: deposits of the protein amyloid-β, known as plaques, and dense fibrils of the protein tau, now called neurofibrillary tangles. Deter died in a psychiatric institution, curled up in the fetal position, of sepsis caused by bedsores.

Nature Outlook: Alzheimer’s disease

The standard of care has improved, but Alzheimer’s disease can still seriously lower quality of life — especially for women. Two out of every three people with Alzheimer’s are women, and the greatest risk factor after old age is being a woman. These discrepancies go beyond the overall prevalence too: typically, women are diagnosed later than men and decline faster. Despite these clear patterns, sex and gender differences have been neglected in the study of Alzheimer’s. “We owe women a century of research,” says Lisa Mosconi, a neuroscientist and director of the Cornell Weill Women’s Brain Initiative in New York City.

Over the past decade, researchers have been working to correct this inequity by studying the effects of sex and gender on Alzheimer’s risk, pathology and progression. Investigations into the role of the X chromosome and the transition to menopause are providing insights into women’s cognitive resilience, and fuelling fresh ideas about how Alzheimer’s pathology might be stopped. “We still we have far to go and more to do,” says Dena Dubal, a neurologist at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). The hope is that these efforts will lead to better care not just for women, but for everyone with the disease.

Just as this research is beginning to bear fruit, however, it has come under threat in the United States. In response to a flurry of executive orders issued in January, the US National Science Foundation has begun scouring research grants for words implying that they might not comply with the Trump administration’s directives to terminate funding for research on women and minoritized groups, which they lump together with various other efforts the government now disparages as ‘DEI’ (diversity, equity and inclusion). As of early March, the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) had terminated several research grants related to Alzheimer’s disease in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and other people from sexual and gender minorities (LGBTQ+).

A tipping point

Cognitively healthy women show greater resilience as their brains age than men do. Until and unless they develop Alzheimer’s or other forms of dementia, women have better memory, particularly verbal and episodic memory, than do men. This is true throughout life, even in very old age. And as measured by changes in glucose metabolism and epigenetic modifications, men’s brains biologically age more rapidly than do women’s.

Following an Alzheimer’s diagnosis, however, the tables are turned. Compared with men with Alzheimer’s, women with the disease experience more-rapid cognitive decline, lose their independence earlier and spend more time with a greater level of disability. The reasons for this disparity are likely to be both biological and social.

On the biological side of things, Eider Arenaza-Urquijo, a neuroscientist at the Barcelona Institute for Global Health in Spain, thinks that women might be better able than men to resist the gradual accumulation of pathological proteins. “Amyloid and tau may be building up for decades,” she says. Men and women seem to accumulate similar levels of amyloid-β, although there’s some evidence that women carry more tau tangles. But Arenaza-Urquijo thinks that their greater resilience to brain ageing might enable women to fight the effects of both proteins better than men — that is, women accumulate amyloid and tau for longer before showing symptoms.

Antonella Santuccione-Chadha.Credit: Monica Astrologo/ MIRUS

This resistance could also explain women’s apparently rapid cognitive decline after diagnosis — after coping for years, they just can’t do so any longer. The trajectory of sustained resilience, then rapid decline, is visible in comparisons of women’s and men’s cognition for a given burden of amyloid-β. Compared with men, women initially maintain more cognitive function, before declining faster once a tipping point is reached. Structural changes in the brain follow a similar trajectory: women initially maintain more hippocampal volume than do men as they accumulate amyloid-β, but when the burden becomes too great their hippocampal volume plummets faster than in men2.

The way in which Alzheimer’s is diagnosed clinically could also be a factor in women’s apparently rapid decline, says Antonella Santuccione-Chadha, president of the Women’s Brain Foundation in Basel, Switzerland. In many cases, men receive systematically better care. For example, women are more likely than men to be given antipsychotics and antidepressants, which is a proxy for a poor standard of care, says Santuccione-Chadha. And because women tend to have better verbal memory than men, they might need to be assessed using sex-specific tests that can catch signs of dementia earlier. “The scales are not designed to assess nuances between men and women,” Santuccione-Chadha says. “The bias is everywhere.”

X marks the spot

Some researchers are starting to look more closely at one of the most basic drivers of biological sex differences: sex chromosomes. Female bodies and brains are a mosaic, with each cell containing one active X chromosome from either the mother or father; the other X chromosome is, for the most part, silent. Male cells contain only the maternal X and the paternal Y chromosome. People who are intersex might have other combinations of these chromosomes in some or all of their cells, such as XXY.

The X chromosome carries 5% of our genes, and is especially enriched for genes related to brain function and cognition, says Dubal. Yet the sex chromosomes have long been excluded from studies that look for associations between traits and variations throughout the genome, says Dubal. Most studies of the genetics of the X chromosome have focused on its role in conditions that affect reproduction. Last September, researchers published the first X-chromosome-wide association study of Alzheimer’s3, which included more than one million people. It identified a portion of a gene on the X chromosome, one involved in maintaining cells’ internal clean-up mechanisms, as being significantly associated with the disease. This could be linked to the pathological accumulation of amyloid and tau proteins seen in Alzheimer’s.

Dena Dubal talks to colleagues in the laboratory.Credit: UCSF

Dubal uses mouse models to study how the X chromosome might drive sex differences in brain ageing. In 2020, her team at UCSF found that in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s, an extra X chromosome conferred cognitive resilience and helped mice to live longer4. No matter what gonads they had, mice with two X chromosomes were more resilient than those with only one X or with an XY make-up.

Since then, Dubal has begun to examine whether the source of the X chromosome — always the mother for XY individuals — contributes to a person’s resilience to cognitive decline. The answer seems to be yes. In January, Dubal showed that female mice engineered to have only their maternal X chromosome active demonstrated impaired cognition and accelerated brain ageing5. She thinks that this could be linked to the fact that the maternal X has epigenetic modifications that shut down expression of some genes.

The picture might be yet more complex, however. Although the second X chromosome in female cells should be deactivated in the early embryo, Dubal says there is some evidence that “it’s not totally asleep”. Up to 30% of its genes could escape silencing, and that partial doubling up of function could be a source of cognitive resilience in women. Now, Dubal is investigating whether ageing can reactivate the silent X in female cells and animals. Results from her laboratory6 show that ageing increases transcription of the inactivated X chromosome in multiple cells in the hippocampus of mice. One gene that escapes inactivation codes for a component of myelin, the protective coating of nerve cells, and could be a target for future Alzheimer’s therapies. The team found evidence that this might also be happening in cells from an equivalent part of the brain in people.

A disease of midlife?

Research on another difference between biological male and female individuals is showing how the menopause transition, characterized by major changes in the levels of oestrogen and other hormones, might drive sex differences in Alzheimer’s risk and resilience. Medical textbooks describe menopause mainly as the end of reproductive capacities, says Mosconi. But she emphasizes that most menopause symptoms are neurological: hot flushes, poor sleep, mood changes and brain fog.

Mosconi was the first to image the brains of pre-, peri- and post-menopausal women in the context of Alzheimer’s risk. In 2017, her team found that the brains of peri- and post-menopausal women showed more signs of Alzheimer’s than did those of younger women as well as those of age-matched men7. Peri- and post-menopausal women had lower glucose metabolism, reduced brain volume and more amyloid-β deposition in their brains. This pattern has held up in subsequent studies, leading Mosconi to think of Alzheimer’s as a disease of midlife, even though symptoms might not show up for decades. Now, she wants to work out how to intervene in women at risk during this preclinical phase, before cognition begins to decline.

One of the hallmarks of menopause is a drastic decrease in levels of oestrogen, which regulates glucose metabolism in the brains of women (testosterone seems to have a similar role in men). As oestrogen levels fall during menopause, so does the brain’s glucose metabolism. To compensate, the brain switches over to burning fats as fuel. Most women weather this metabolic change and recover some of the lost brain volume, and symptoms such as brain fog typically resolve in four to six years.

This is not the only major hormone-driven change that a woman’s brain must withstand — puberty and pregnancy also pose challenges, Mosconi says. In general, “the brain shows the capacity to adapt”, she says. But this is not always the case after menopause. Some women do not recover cognitively, and Mosconi is investigating how brain fog during peri-menopause might be linked to the risk of developing Alzheimer’s in later life. Her hypothesis, she says, is that “for some people, the decline is progressive and leads to Alzheimer’s disease”.

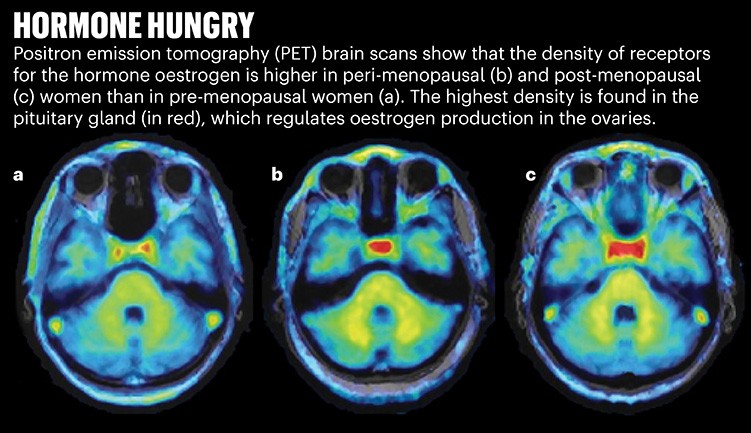

Mosconi worked with radiochemists to develop a fluorescent tracer that binds to oestrogen receptors in the brain. Last June, the team showed that, in parts of the brain regulated by the hormone, there is a greater density of oestrogen receptors in peri- and post-menopausal women8. That increased density was correlated with memory problems (see ‘Hormone hungry’).

Source: Adapted From Ref. 8.

Mosconi thinks that this is evidence of an ageing brain, hungry for the ever-scarcer hormone, making more receptors to try to catch what oestrogen it can. This greater density was seen even in the oldest woman in the study, who was 65. Mosconi says these early findings suggest that it’s worth exploring whether oestrogen therapy, which has gone in and out of fashion as a treatment for menopause symptoms, could provide cognitive benefits and potentially stave off clinical symptoms of Alzheimer’s in women at risk.

Diverse data

Although researchers have spent about a decade learning more about how biological sex plays a part in Alzheimer’s risk and progression, they’re just at the beginning of untangling the contribution of gender. Some disease risk is related to social roles, which are influenced by how people’s gender and sexual orientation affects both their behaviour and how they are treated in the world. For instance, women are more likely than men to provide care for ailing family members, which contributes to a greater risk of depression and sleep problems — both risk factors for developing Alzheimer’s. “It’s really difficult to separate the biological from the social and behavioural,” says Jason Flatt, a public-health researcher at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Sexuality, too, could be a confounding factor. Social roles play out differently in different relationships. In a gay couple, for instance, one partner might take on the care-providing role, along with any associated health risks. Rates of stress, alcoholism and depression — known risk factors for Alzheimer’s — are also higher in LGBTQ+ people.

Scientists have so far not gathered much data about how experiences particular to sexual and gender minorities influence the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. A 2024 review of cognitive impairment in LGBTQ+ people found only 15 eligible studies to assess9. The review found that self-reported cognitive impairment was higher among LGBTQ+ people, but the evidence on objective differences in cognitive performance was mixed.

Studies of older couples have found that people in same-sex relationships have a risk of cognitive impairment that is nearly 80% higher than for people in mixed-sex relationships10. Same-sex couples are also more likely to experience depression, a risk factor for cognitive impairment. People who don’t conform to social norms around gender and sexuality might also be more likely to have traumatic experiences that increase Alzheimer’s risk. A 2024 study by Flatt and their colleagues found that trans, non-binary and other gender-diverse people are more likely to have had adverse childhood experiences, which have been linked with greater risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease11.

In February and March, Flatt’s research grants from the National Institute on Aging, totalling almost US$5 million, were cancelled. Flatt says they are planning to appeal the termination, but might have to lay off staff and students in their lab.

One of the termination letters, signed by grants administrator Jessica Kaufman, asserted that “many such studies ignore, rather than seriously examine, biological realities”. But researchers investigating the role of sex and gender in Alzheimer’s disease say examining biological realities is exactly what they are trying to do — and that historical data-gathering practices have created obstacles to this.

Despite US regulations that have required the inclusion of women in NIH-funded clinical trials since 1993, and that designate LGBTQ+ people as a group affected by health disparity (a designation adopted by the NIH in 2016), it remains common for human studies of Alzheimer’s disease to exclude women, intersex, transgender and non-binary people, or to not record them in the data. As of late March, the NIH page laying out parameters and definitions to guide research on minority health and disparities has been deleted.

Sometimes, researchers statistically factor biological sex differences out of their results deliberately, says Mosconi. “The preconception is that women are like small men,” Santuccione-Chadha says.

More from Nature Outlooks

Flatt is part of an LGBTQ+ interest group that has proposed best practices for gathering data about sexual orientation, sex assigned at birth and gender identity of study participants, and for including intersex people — nearly 2% of the US population — in dementia research. The National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center, which is funded by the US National Institute on Aging, adopted these guidelines in its participant demographics questionnaire in January. Flatt says the main pushback is from scientists who are concerned that people will be offended and drop out of studies if are asked about their sexual orientation and gender identity. But Flatt adds that there is no evidence of this happening.

Santuccione-Chadha says that considering sex and gender is the most obvious step towards precision medicine in Alzheimer’s and many other diseases. A future medical system focused on personalized care, she says, needs to include gender, sex, social status and much more alongside genomics. She’s also advocating that pharmaceutical companies include an equal number of women in clinical trials — or run clinical trials specifically for women.

“It is imperative that we, as the US, continue to forge the way in biomedical research and champion medical care for all, including the underserved, the minoritized, and the historically neglected,” says Dubal. “This includes advancing the rigorous study of biological sex, gender and women’s health — among many critical priorities.” Instead of abandoning this work, as now seems possible in the United States, it should be expanded, Dubal says, to improve people’s health and save lives.