Children are taught about the conduction of electricity at a science festival in China.Credit: Costfoto/NurPhoto via Getty

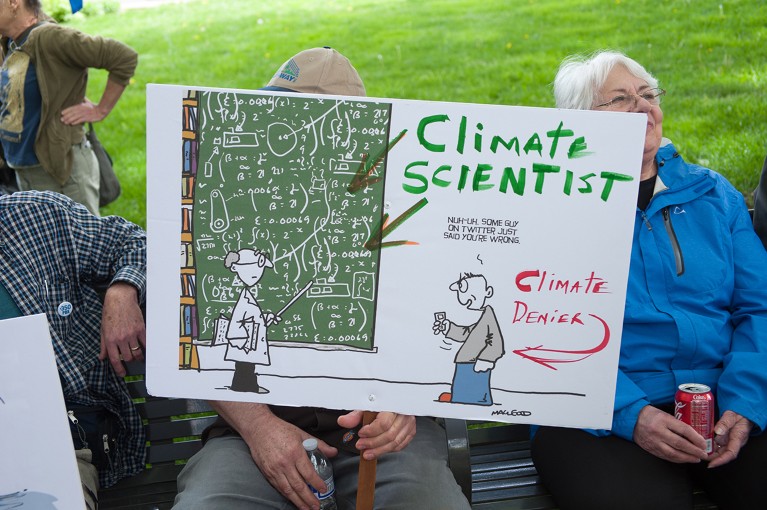

Around the world, the scientific community is confronting challenges to its cultural authority. Funding is under pressure, expertise is subject to political attack, and vaccine scepticism and disputes over climate policy are rife1. This is often interpreted as a problem of the public — a result of limited scientific literacy, declining trust in experts and misinformation — rather than of science itself. Yet, working with limited assessment tools, it is striking how little knowledge researchers have about the extent to which the public understands science2.

Science’s big problem is a loss of influence, not a loss of trust

Scientists and researchers who study public understanding should reckon with their own role in this cultural disconnect. In particular, they need to reimagine the ways in which scientific literacy and trust have long been conceptualized and measured. For decades, researchers have relied mainly on surveys — asking what people know or how much confidence they have in scientists and experts. These questions have yielded important insights. But they have also perpetuated gaps in knowledge.

A broader approach is needed, which I outline here. Scientists need to carefully examine the public’s understanding of how the scientific enterprise operates and how its institutions work, as well as the contexts in which people experience science, both positively and negatively.

Consider more than facts

The limitations of measures of science literacy over time and across populations are well established3. Early efforts assessed an individual’s capacity to engage with scientific information as a technical form of civic competence, such as the ability to comprehend popular-science magazines or the science section of a newspaper4. Over time, such measures came to stand in for broader claims around public understanding5. And the distinction blurred between knowing scientific facts and understanding how science operates as a social and institutional enterprise.

How to get science back into policymaking

Gaps in public knowledge are dramatized6. For example, widely used tools ask respondents whether the Earth revolves around the Sun — a question that, across multiple surveys, roughly one-quarter of respondents answer incorrectly. Questions about genetic probability test numeracy and reasoning around genetics, and also generate high rates of incorrect responses. Yet low science-literacy scores say little about how people evaluate scientific information, assess expertise or reason about science’s role in society.

Evaluations of trust are also too simplistic. Many people express confidence in scientific methods and expertise but also question how science is governed, funded or applied in public decision-making. Standard measures of trust tend to collapse these distinctions, and do little to explain why credibility is granted or withdrawn.

Health workers administer COVID-19 vaccines in Thailand.Credit: Vachira Vachira/NurPhoto via Getty

Public understanding of the institutions of science — how science as a profession works, the commitments involved and whether the scientific community is perceived to be living up to them — is clearly important for judging credibility7. In everyday controversies, over vaccines, environmental regulation or emerging technologies, public concerns hinge on transparency, independence, accountability and the handling of uncertainty8. Yet institutions and the scientific community itself have rarely been focuses of research into public understanding.

The problem is not that existing measures are wrong, but that they are incomplete: they remove science from the contexts in which it is encountered, evaluated and judged. This omission is a big reason why the current moment is being misdiagnosed as a crisis of public literacy or trust, when it might instead reflect a deeper neglect of public matters. What is needed, then, is a shift in how the public understanding of science is conceptualized and measured — one that puts science’s institutions at its centre, including the norms and practices through which credibility in the public sphere is earned, contested and lost.

Address science’s cultural meaning

A new science of public understanding would begin by broadening the definition of understanding to include an emphasis on how science operates and what is expected of it. Rather than treating science as an abstract source of facts or authority, this approach focuses on its cultural meaning as a social and institutional system — a professional enterprise with organizations, incentives and norms.

How to speak to a vaccine sceptic: research reveals what works

From this perspective, public understanding unfolds across three areas: shared knowledge of the norms and practices that organize scientific work; public expectations about what scientists and scientific organizations should do for society; and judgements about the distance between those ideals and perceptions of science as it is practised.

Sociology offers criteria for distinguishing what makes research scientific in the first place, while also serving as the scaffolding through which scientific credibility is claimed, evaluated and sustained. For example, US sociologist Robert K. Merton described four principles — universalism, communalism, disinterestedness and organized scepticism — as the ethos of science9. Although there is growing evidence that these norms feature prominently in the public view of what matters about science10, such factors have rarely been incorporated into large-scale surveys, in which measures of literacy and trust still dominate.

People in Portland, Oregon, and other cities around the world participated in a day of action against climate change in 2017.Credit: Diego Diaz/Icon Sportswire via Getty

Reorienting the science of public understanding requires asking how the public apprehends these norms in practice. Surveys could ask, for example, whether credibility is seen as grounded in advanced training, rigorous evidence, replication and openness to alternative interpretations.

They could also measure how the public evaluates science’s role in society and governance. Questions about whether scientists should avoid challenging deeply held beliefs, or whether strong scientific evidence should guide policy when it conflicts with public opinion, would capture how people reason about the boundaries, authority and obligations of science — and illuminate where deep cultural disagreement persists. (For examples of survey questions, see Supplementary information.)