The world has entered an era of increasing ecological scarcity and rising environmental risks. Since 1970, 75% of terrestrial and 66% of marine environments have been altered by human use, climate change, pollution, species loss and invasion1. Some 14 out of 18 global ‘ecosystem services’ have declined, including the stability of the climate, the numbers of pollinators and quantity and the quality of fresh water1. The average size of wildlife populations has plummeted2 by 73%.

Six roadblocks to net zero — and how to get around them

How economies respond to these issues will be crucial to their prosperity and sustainability3. If nature is valued, and a high price is placed on its exploitation and use, scarcity can create incentives to innovate and substitute. For example, as the cost of converting forests, wetlands and grasslands to farmland rises and fresh water becomes scarce, it becomes increasingly attractive to use agricultural methods that consume less land and water. But if economies choose to continue exploiting or polluting nature, for instance by converting forests to agricultural land, extracting minerals from the sea bed, dumping plastics in the ocean and expanding fossil-fuel reserves, then the costs for humanity and the environment will soar.

So far, countries are choosing distinct approaches. And two trends are emerging: some nations are ignoring the damage to nature to keep the costs of resources and pollution artificially low, whereas others are embarking on a competitive race to dominate green innovation and markets.

Here, I describe those trends and make the case that, in the long run, the green-technology race is likely to prevail. But the result of this competition might be more prosperity at the expense of less sustainability, unless it is accompanied by global cooperation to solve shared environmental risks.

Barriers to the green transition

Nature’s most valuable services — a stable climate, support for food and agricultural systems and protection of people’s lives, health and property — are provided for free. They do not appear in markets and are mostly ignored in policy and business decisions.

Worse, governments provide economic incentives for activities that can harm the environment4,5. Examples include subsidies to lower the cost of coal for electricity, water, pesticides and fertilizers for crops, cutting down forests for timber and trawling sea beds. Such environmentally harmful incentives for fossil fuels, agriculture, water, forestry, construction, transport and fisheries amount to roughly US$1.8 trillion each year globally6. This is about 2% of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP).

A company in Canada uses renewable hydroelectric energy sources for its greenhouse crops.Credit: Darryl Dyck/The Canadian Press/Alamy

Because nature is being underpriced, most economies disregard the increasing costs of ecological scarcity. They don’t view natural systems as assets worth conserving, restoring and protecting through investment4. For example, global spending on biodiversity and habitat conservation, protection and restoration ranges from $124 billion to $143 billion a year7. Yet this is only up to one-fifth of what’s needed — translating into a biodiversity-financing gap of more than half a trillion dollars.

Businesses, too, are investing insufficiently in nature. More than half of the world’s GDP, or around $44 trillion of global value added by 163 industry sectors and their supply chains, depends on nature and its services8. Yet, companies worldwide are investing only a fraction of that ($5.5 billion to $8.2 billion annually) in making their supply chains environmentally sustainable7.

The green race

Despite this shortfall, some economies and businesses have recognized that they can gain from becoming greener by exploiting their competitive and technological advantages. The result is an emerging green race over key global markets, innovations and investments, including clean energy, renewable industrial products and processes and markets for carbon, biodiversity and water credits.

How scientists can drive climate action: celebrate nature and promote hope

Several countries, including China, Germany, France, Italy, Japan, South Korea, the United Kingdom and the United States, have the potential to become market leaders by competing over the greening of key manufacturing sectors, such as vehicle innovation, electricity generation and other industrial processes and durable consumer goods9. Nations with high green-production capabilities are likely to have more patents for environmental technologies, lower carbon dioxide emissions and more stringent environmental policies than those without such capacities10.

Globally, the proportion of companies with green products and services has been growing11. But this expansion is spread unevenly. Although the United States accounts for 60% of global green stocks, their share in terms of the total US market is only 8%, implying that the US economy is less green than the global average of 9%11. Taiwan, Germany, Canada, Japan, China and France exceed this average, suggesting that their economies are well positioned for success in the green race11.

The competition is driven by the slowing growth in productivity of the global economy since the 1980s12,13, as well as by increasing opportunities for returns and productivity gains in emerging green sectors. Improving nations’ capacity to avoid natural disasters, which can cause a drop in labour productivity — 70% of which are climate-related12 — might also motivate governments to invest in reducing environmental risks.

A facility for recycling carbon fibre in Taiwan, an emerging leader in the global green economy.Credit: Lam Yik Fei/Bloomberg via Getty

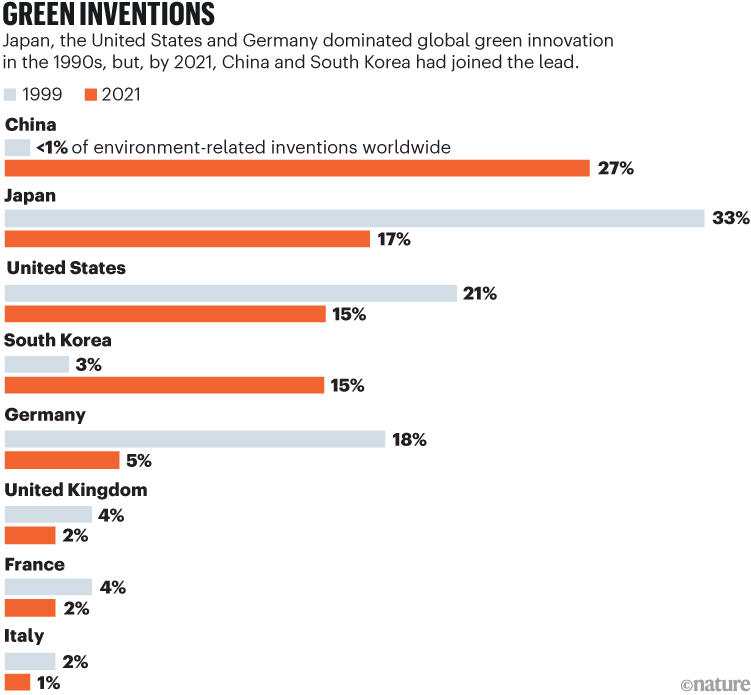

Public policy is responding, as interested governments vie to win the competitive and fast-changing green race. For example, in the 1990s, Japan, the United States and Germany dominated global green innovation (see ‘Green inventions’). But now, China and South Korea have joined Japan and the United States as leaders, after investing heavily in solar and wind energy, batteries and electric vehicles.

Source: OECD Green Growth Dataset (2024); go.nature.com/42uyajf

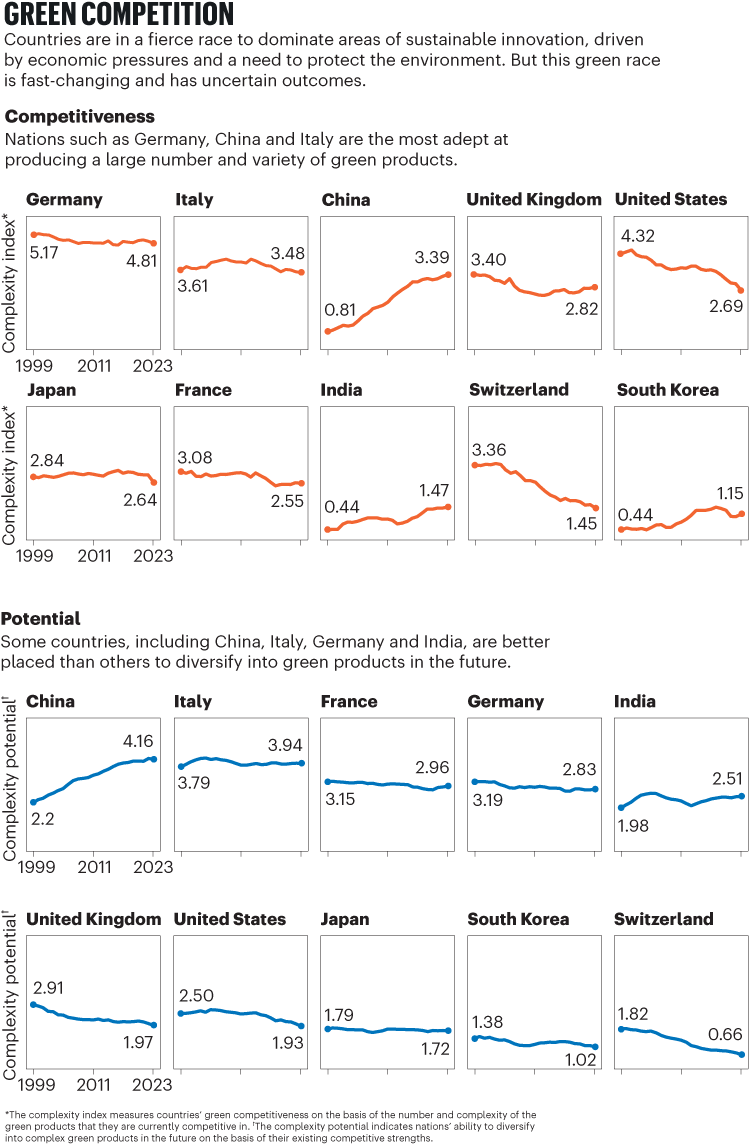

Similarly, countries that are currently competitive in green products and production processes, including Japan, the United States and the United Kingdom, might be overtaken by India and France (see ‘Green competition’). Other nations, such as Spain, Turkey and Poland, are also increasing their investment in these areas (see go.nature.com/4jlrsad).

Source: P. Andres and P. Mealy, Green Transition Navigator (London School of Economics & Political Science, 2023); see go.nature.com/4jlrsad

Counterproductive measures

All of this green competition might speed up the development of sustainable technologies and reduce the pressure on the planet. But it could also result in the rise of ‘green mercantilism’, if countries adopt protective strategies to enhance their competitive advantage in the global green market.

There are signs that the latter is happening. After the United States implemented the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act, many large economies, including the European Union, China and India, followed its example and shifted their green industrial policies to openly adopt protectionist provisions, such as tax breaks, procurement requirements and loans and subsidies that favour domestic sectors and industries at the expense of international competitors14.