The space industry is expanding fast — and its value is set to triple in the next decade, from US$630 billion in 2023 to $1.8 trillion by 2035. However, although the number of nations with space programmes is growing — with 77 space agencies worldwide — many others are excluded.

In particular, many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), Indigenous Nations and communities and small states are missing from debates around space activities. Their concerns around how people operate in space, the environmental consequences, Indigenous rights, diverse views of cosmology and demands for political and scientific participation are typically dismissed.

Such marginalization has created tension between these communities and the astronomy and space sectors. For example, in Hawaii, Indigenous communities are opposing the construction of telescopes on the summit of Maunakea — a sacred site. And in 2024, people of the Navajo Nation contested a (failed) commercial attempt to send human remains to the Moon, an act that was deeply upsetting to them and many others1.

Swarms of satellites are harming astronomy. Here’s how researchers are fighting back

Objections by LMICs and Indigenous communities, such as those in French Guiana and Sweden, to space projects often frame space expansion as a type of colonialism and ecological exploitation. Politicians and technology moguls portray space exploration and colonization as the logical next step in humanity’s journey and use colonial language and imagery, such as planting flags, to describe humankind’s voyages into space. This tension between the desire to go into space and who this desire benefits and affects lays bare the differences between dominant Western systems of knowledge and science and those of Indigenous communities. And controversies are not limited to space; launch and research and development facilities on the ground can also be exclusionary.

For example, on 3 May, the residents of Starbase — a community in Texas made up of mainly employees who work for the astronautics company SpaceX — voted to become a city. This designation could give the company authority over Boca Chica beach where SpaceX conducts its launches. This has provoked vigorous opposition, including concerns that SpaceX does not have consent from the Indigenous people whose ancestral lands SpaceX is polluting and enclosing.

Making an inclusive and just space programme that is empowered by diverse world views presents enormous challenges. Some Indigenous groups and activists, such as Christopher Basaldú, co-founder of the South Texas Environmental Justice Network in Brownsville, argue that it is impossible in an industry so rooted in capitalism and colonialism. Yet most people would agree that space exploration must look beyond profit return and narrow scientific goals.

Here, we, a group of academics and Indigenous scholars from five countries, outline these challenges and call for greater efforts to include all of humanity in discussions of and activities around space. We would like to chart a course towards inclusive and anti-colonial space exploration on the basis of collaboration, consultation, respect, responsibility and mutual benefits for Indigenous people, small nations and other marginalized groups.

A frontier for some, not all

Despite having lofty goals that space should be explored for the benefit and in the interests of all humankind, international multilateral agreements on human uses of space offer few avenues for including diverse perspectives. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty does not explicitly include Indigenous rights. And the widespread rejection of the 1976 Bogota Declaration, in which equatorial nations called for ownership of the geostationary orbits over their Earthly territories (following Western land law), illustrates how smaller powers are typically ignored.

Although those nations’ claims were dismissed as an attempt to appropriate outer space, many Western countries today are doing just that by adopting permissive legislation and multilateral agreements to assure their abilities to exploit off-planet resources. For example, looking ahead to crewed missions to the Moon and Mars, since 2020 more than 50 countries have signed the Artemis Accords, a set of principles developed by the US government, NASA and 7 other initial signatory nations to guide civilian space exploration based on the Outer Space Treaty.

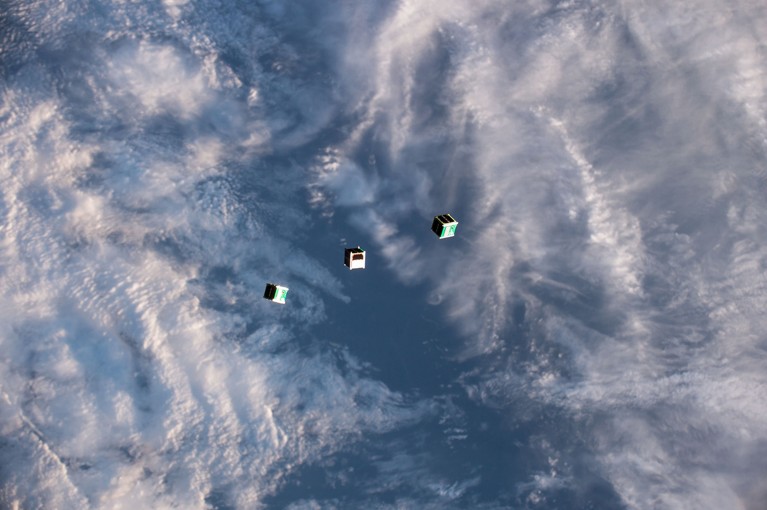

A joint global satellite project called BIRDS, which is supported by Japan, aims to help non-spacefaring nations build their first satellite.Credit: Jack Fischer/JSC/NASA

Such exclusive rights to space are concerning if sites on the Moon will come to be viewed as ‘land’ for the purposes of exploitation. Although there is a growing discussion about what constitutes ‘outer space heritage’ and who will decide how humans will act on the Moon, current governing regulations, liability regimes, policy guidance and best practices are limited and ignore Indigenous perspectives. The Artemis Accords might be an avenue to increase Indigenous involvement in space by enhancing transparency, strengthening international collaboration and preserving outer space history, but only if signatory nations act to support Indigenous rights at the same time.

Yet, because there is no one Indigenous perspective or body of knowledge, such diverse communities hold varied views on the future of space projects. Not all oppose all forms of space futures, and each has its own view of them. Constructive critiques of exclusionary practices should be recognized as advocacy for equity, responsibility and respect, rather than being conflated as outright hostility to astronomical and space programmes.

Community benefits

The partnering of Indigenous communities with space sciences and the space industry can bring benefits to all. It can enhance ways of exploring space collectively and enable innovations. For instance, emerging space nations, such as Bhutan, Nepal and Thailand, showcase how LMICs have the potential to contribute diverse world views to space exploration.

Space debris is falling from the skies. We need to tackle this growing danger

Australia is one example, it is both an emerging space actor and a state that is struggling to create a robust space industry that is inclusive of First Nations communities. Its proximity to the equator and clear skies make the country an ideal location for launch sites and ground stations.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are world leaders in Indigenous engagement with the space industry. For example, the Centre for Appropriate Technology is an Aboriginal-owned business that, in 2020, opened Satellite Enterprises — an Earth station to communicate with satellites and tap into the space economy2.

The National Indigenous Space Academy, based at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, is working with NASA to train the next generation of First Nations astronauts and science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) workers (see go.nature.com/3gtdkue). The Australian Space Agency hosts a First Nations Engagement Team, and emerging Indigenous space-related organizations are popping up across the country, such as Gunggandji Aerospace, a consultancy company in Cairns, Queensland, that brings aerospace expertise and First Nations insights to Australia’s space industry, founded by Daniel Joinbee, a member of the Gunggandji people.

Despite such engagement, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities face challenges in being able to benefit from the space industry economically. Sluggish Australian bureaucratic processes and thorough Indigenous protocols regarding community consultation hinder market competitiveness.

For these reasons, in 2024, Equatorial Launch Australia — a space launch company — closed its Arnhem Space Centre site (see go.nature.com/4dpgsj2). Many Gumatj community members are disappointed that they have been deprived of this economic foundation for the region, which would help the area to transition away from destructive practices such as mining. Equatorial Launch Australia is now moving to another site in Queensland, wasting time, money and opportunities for equity.

Without overcoming these obstacles in a mutually beneficial way, First Nations communities will miss out on the interactions and financial benefits from space facilities that are developed on their lands, waters and in the sky. The space industry will be less rich in ideas.

Demonstrators protest the construction of a telescope on Maunakea in Hawaii.Credit: Ronit Fahl/ZUMA Wire

Another notorious example is the controversy surrounding the construction of the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) on Maunakea in Hawaii. Proponents of the telescope argue that it would provide researchers with the tools to do groundbreaking astronomical research. Opponents, including many Kānaka Maoli (the Indigenous peoples of Hawaii) leaders and citizens and other Indigenous environmental activists and allies, argue that its construction would represent further desecration of a sacred site (see go.nature.com/3srgcpr).

The fault lines here do not necessarily fall on ethnic divisions — not all Kānaka Maoli oppose the TMT and many Haole (people who are not Native Hawaiian) are allied with the protesters (see go.nature.com/43uhmh2). More conceptual, systemic and interpersonal work needs to be done to find common ground.