Young, successful AI researchers are increasingly choosing to leave academia for industry.Credit: Costfoto/NurPhoto via Getty

In 2025, Google, Amazon, Microsoft and Meta collectively spent US$380 billion on building artificial-intelligence tools. That number is expected to surge still higher this year, to $650 billion, to fund the building of physical infrastructure, such as data centres (see go.nature.com/3lzf79q). Moreover, these firms are spending lavishly on one particular segment: top technical talent.

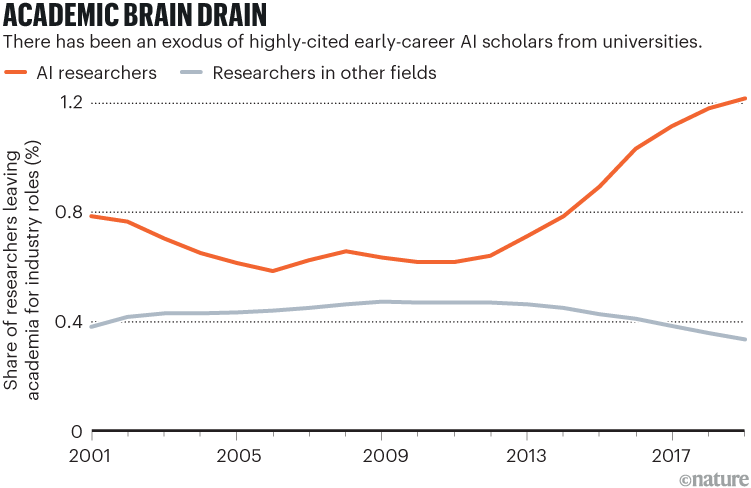

Meta reportedly offered a single AI researcher, who had co-founded a start-up firm focused on training AI agents to use computers, a compensation package of $250 million over four years (see go.nature.com/4qznsq1). Technology firms are also spending billions on ‘reverse-acquihires’ — poaching the star staff members of start-ups without acquiring the companies themselves. Eyeing these generous payouts, technical experts earning more modest-salaries might well reconsider their career choices (see ‘Academic brain drain’).

Academia is already losing out. Since the launch of ChatGPT in 2022, concerns have grown in academia about an ‘AI brain drain’. Studies point to a sharp rise in university machine-learning and AI researchers moving to industry roles. A 2025 paper reported that this was especially true for young, highly cited scholars: researchers who were about five years into their careers and whose work ranked among the most cited were 100 times more likely to move to industry the following year than were ten-year veterans whose work received an average number of citations, according to a model based on data from nearly seven million papers1.

Source: Ref. 1

This outflow threatens the distinct roles of academic research in the scientific enterprise: innovation driven by curiosity rather than profit, as well as providing independent critique and ethical scrutiny. The fixation of ‘big tech’ firms on skimming the very top talent also risks eroding the idea of science as a collaborative endeavour, in which teams — not individuals — do the most consequential work.

Here, we explore the broader implications for science and suggest alternative visions of the future.

Myth of lone genius

Astronomical salaries for AI talent buy into a legend as old as the software industry: the 10x engineer. This is someone who is supposedly capable of ten times the impact of their peers. Why hire and manage an entire group of scientists or software engineers when one genius — or an AI agent — can outperform them?

That proposition is increasingly attractive to tech firms that are betting that a large number of entry-level and even mid-level engineering jobs will be replaced by AI. It’s no coincidence that Google’s Gemini 3 Pro AI model was launched with boasts of ‘PhD-level reasoning’, a marketing strategy that is appealing to executives seeking to replace people with AI.

But the lone-genius narrative is increasingly out of step with reality. Research backs up a fundamental truth: science is a team sport. A large-scale study of scientific publishing from 1900 to 2011 found that papers produced by larger collaborations consistently have greater impact than do those of smaller teams, even after accounting for self-citation2. Analyses of the most highly cited scientists show a similar pattern: their highest-impact works tend to be those papers with many authors3. A 2020 study of Nobel laureates reinforces this trend, revealing that — much like the wider scientific community — the average size of the teams that they publish with has steadily increased over time as scientific problems increase in scope and complexity4.

Why an overreliance on AI-driven modelling is bad for science

From the detection of gravitational waves, which are ripples in space-time caused by massive cosmic events, to CRISPR-based gene editing, a precise method for cutting and modifying DNA, to recent AI breakthroughs in protein-structure prediction, the most consequential advances in modern science have been collective achievements. Although these successes are often associated with prominent individuals — senior scientists, Nobel laureates, patent holders — the work itself was driven by teams ranging from dozens to thousands of people and was built on decades of open science: shared data, methods, software and accumulated insight.

Building strong institutions is a much more effective use of resources than is betting on any single individual. Examples demonstrating this include the LIGO Scientific Collaboration, the global team that first detected gravitational waves; the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard in Cambridge, Massachusetts, a leading genomics and biomedical-research centre behind many CRISPR advances; and even for-profit laboratories such as Google DeepMind in London, which drove advances in protein-structure prediction with its AlphaFold tool. If the aim of the tech giants and other AI firms that are spending lavishly on elite talent is to accelerate scientific progress, the current strategy is misguided.

By contrast, well-designed institutions amplify individual ability, sustain productivity beyond any one person’s career and endure long after any single contributor is gone.

Equally important, effective institutions distribute power in beneficial ways. Rather than vesting decision-making authority in the hands of one person, they have mechanisms for sharing control. Allocation committees decide how resources are used, scientific advisory boards set collective research priorities, and peer review determines which ideas enter the scientific record.

And although attempting ‘innovation by committee’ might sound disparaging, such an approach is crucial to make the scientific enterprise act in concert with the diverse needs of the broader public. This is especially true in science, which continues to suffer from pervasive inequalities across gender, race and socio-economic and cultural differences5.

Need for alternative vision

This is why scientists, academics and policymakers should pay more attention to how AI research is organized and led, especially as the technology becomes essential across scientific disciplines. Used well, AI can support a more equitable scientific enterprise by empowering junior researchers who currently have access to few resources.

Instead, some of today’s wealthiest scientific institutions might think that they can deploy the same strategies as the tech industry uses and compete for top talent on financial terms — perhaps by getting funding from the same billionaires who back big tech. Indeed, wage inequality has been steadily growing within academia for decades6. But this is not a path that science should follow.

If the AI bubble bursts, what will it mean for research?