When Lisa Dutton was declared free of breast cancer in 2017, she took a moment to celebrate with family and friends, even though she knew her cancer journey might not be over. As many as one-third of people whose breast tumours are cleared see the disease come back, sometimes decades later. Many other cancers are known to recur in the years following an initial treatment, some at much higher rates.

“It’s always in the back of your mind, and that can be stressful,” says Dutton, a retired health-care management consultant living in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Cancer-fighting immune cells could soon be engineered inside our bodies

As part of her treatment, Dutton had enrolled in a clinical trial called SURMOUNT. This would monitor her for sleeping cancer cells, which many researchers now think might explain at least some cancer recurrence1. These dormant tumour cells evade initial treatment and move to other parts of the body. Instead of multiplying to form tumours right away — as is typical for metastatic cancer, in which cells spread from the main tumour — the dormant cells remain asleep. They are hidden from the immune system and not actively dividing. But later, they can reawaken and give rise to tumours.

Even though Dutton understood that her treatment might not have removed all signs of cancer, she says she was floored in 2020 when dormant cells were found in her bone marrow for the first time.

Researchers are discovering dormant tumour cells, also known as disseminated cancer cells, in association with breast, prostate, lung, colon2 and other cancers, and these cells are increasingly implicated in some metastatic cancers. An estimated 30% of people who have been successfully treated for cancer might harbour these cells, although unpublished work suggests they could be even more common.

Over the past decade, a flurry of efforts have attempted to identify and understand dormant cells, with the ultimate goal of treating them. A handful of clinical trials are now under way to test potential therapies.

Although the first trial Dutton enrolled in only monitored the cells, she has since enrolled in a second, called CLEVER, that aims to eliminate them3. As such trials move ahead, open questions about the sleeper cells, including what induces dormancy and how to fight it, are drawing more researchers into the field.

“We’re starting to see multiple groups converging on some of the same ideas, which is always very affirming,” says Cyrus Ghajar, a cancer biologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Seattle, Washington. The trials under way are “a testament to just how much progress has been made”.

A silent threat

The existence of dormant tumour cells was proposed as early as the 1930s, when Australian pathologist Rupert Willis attributed some secondary cancer growths to such cells4. As people who had been treated for cancer began to live longer, he and others noticed that the disease sometimes returned much later, and was often even more aggressive. Despite this early proposal, the idea of dormancy didn’t catch on for decades.

Lewis Chodosh, a physician-scientist at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, recalls facing resistance when he began discussing the idea with colleagues more than 20 years ago. No one wanted to believe that cancer-killing drugs might be leaving something behind, he says, and drug companies weren’t interested in developing therapies for people who seemed to have been cured. Many scientists at the time said that recurrent cancers must instead be new, not linked to any past diagnoses.

“It’s only when enough evidence accumulates that you get pushed out of this way of thinking,” says Chodosh, who is a co-investigator on the SURMOUNT and CLEVER studies alongside Angela DeMichele, a medical oncologist at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine.

Angela DeMichele (left) and Lewis Chodosh are investigating ways to target dormant tumour cells.Credit: Peggy Peterson for Penn Medicine

Using a handful of cellular markers, researchers have now identified dormant tumour cells in many parts of the body5. These markers can tell scientists not only whether the cells are growing and dividing, but also where the cells originated and therefore which type of cancer they’re associated with. The methods aren’t perfect, however, and researchers are still trying to determine whether certain cells are more likely to go dormant than others, and which features define these cells.

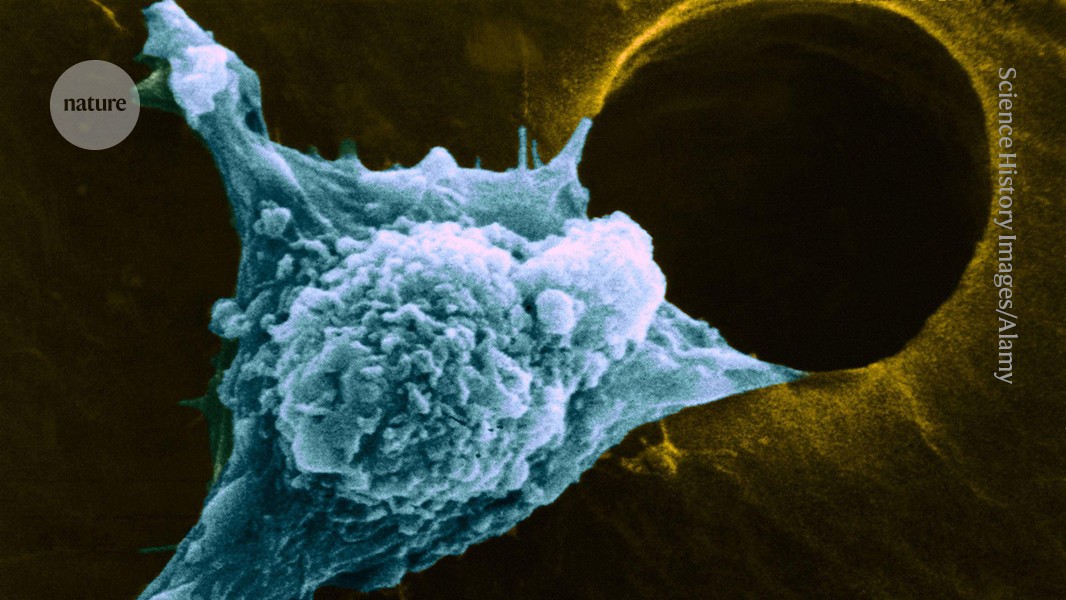

Ghajar and others have found that dormant cells leave the primary tumour early in a cancer’s progression, often before the disease has been diagnosed6. How and why these cells break away isn’t entirely clear, but after spending just minutes in circulation, they exit the bloodstream and concentrate in certain parts of the body, such as the bone marrow and lymph nodes. Even in these niches, dormant cells are extremely rare, amounting to just a handful among millions of healthy cells, he says. Their state of suspended animation shields them from conventional treatments, such as chemotherapy, that target rapidly dividing cells.

Petros Tsantoulis, a medical oncologist at the University of Geneva in Switzerland, says that dormancy differs from other known states such as senescence, in which old cells stop dividing as they prepare to die. Given the right conditions, dormant cells can begin dividing anew. Once reawakened, dormant cells multiply into tumours that replicate the full complexity of the original tumour.

This has led some researchers to suggest that dormant tumour cells might be cancer stem cells, a type of cell that through renewal and differentiation might give rise to the tumour — or that, at least, they might be cancer cells with stem-like features.

Forget lung, breast or prostate cancer: why tumour naming needs to change

Dormant tumour cells have some characteristics that are commonly associated with stem cells, such as the overexpression of certain genes. Cancer biologist Joan Massagué, director of the Sloan Kettering Institute in New York City, says that stem cells spend most of their time dormant, waking only after an injury or illness — making them obvious candidates. Still, the existence of cancer stem cells is a contentious idea.

Scientists seem poised to resolve some of these open questions soon. With advanced laboratory techniques that give researchers the ability to study individual cells more closely, it’s now possible to identify, isolate and enrich dormant tumour cells for further study. Chodosh and DeMichele’s team, for example, is developing an assay to identify dormant cells. Chodosh says it is much more sensitive than existing approaches, and might ultimately improve estimates of how many people harbour dormant cells.

Ghajar, meanwhile, is settling on a different way of thinking about these cells. If a dormant cell from a breast tumour ends up in the bone marrow, for example, it might be expected to retain many features of a breast cancer cell that would enable its identification. “But what we’re finding is that these expectations don’t hold up,” Ghajar says, noting that once a cancer cell spreads, it often changes its shape, size and behaviour. “We’re going to have to go beyond a definition based on unifying features, and instead map the mutations in these cells to mutations in the originating tumour — to define a disseminated cell not by what we think it should look like, but what its genome tells us it is.”

Sleep–wake signals

Beyond defining dormancy, researchers want to understand how and why cells go dormant, and what sorts of triggers reawaken them.

According to Judith Agudo, an immunologist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts, cells probably enter dormancy as a protective measure. As part of a tumour, individual cells might be insulated from attack by the immune system, but once on their own, “they can easily be picked off without taking steps to hide themselves”, she says. In addition, the journey through the body to a new niche is a stressful one that kills the vast majority of cells that break away. Dormancy is one way of persisting in a harsh environment.

Research has shown that while cells are asleep, they continue to engage in crosstalk with their microenvironment7 and modify themselves to actively maintain dormancy. For example, dormant cells seem to alter the expression patterns of genes involved in cell survival, including a central regulator of cell metabolism and growth called the mTOR pathway8. The cells also exploit a form of self-recycling called autophagy — literally ‘self-eating’ — that allows dormant cells to repurpose internal resources and survive with little input from their surroundings9.

The cells seem to have a complex relationship with their external environment, too, including the immune system. Julio Aguirre-Ghiso, founding director of the Cancer Dormancy Institute at the Montefiore Einstein Comprehensive Cancer Center in New York City, says that the immune response is implicated not only in inducing dormancy, but also in maintaining and ending it.

He and his team have shown that macrophages in the lungs produce a particular protein that binds to dormant breast cancer cells and reinforces dormancy10. Other research has demonstrated how dormant cells can evade surveillance by immune-system cells, including T cells11 and natural killer cells12.

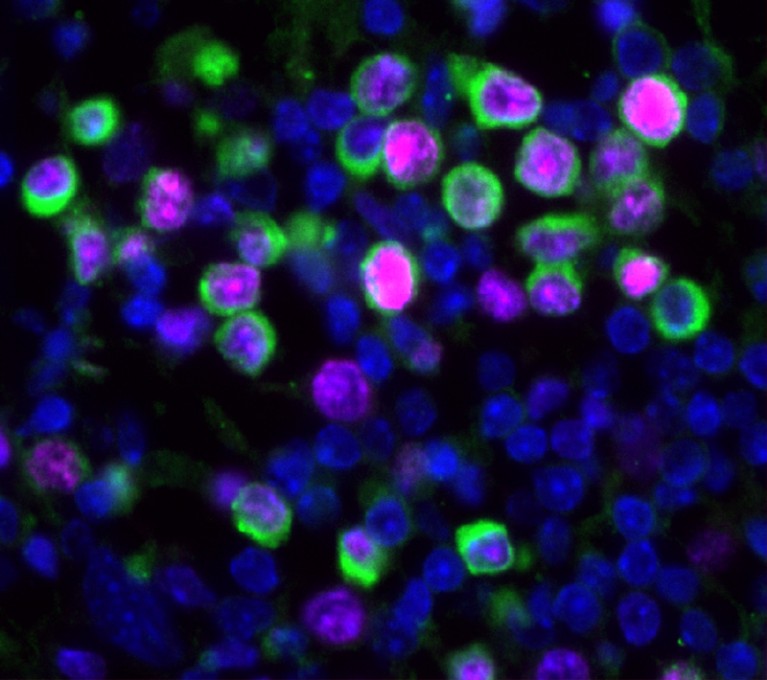

Taken together, the research suggests that cells most often remain dormant until the immune landscape is disrupted in some way, shifting the balance enough for cells to reawaken safely. These shifts might involve injury or illness, with studies in the past few years linking cellular damage13 and COVID-19 and influenza infections14 to an escape from dormancy. Ageing, fibrosis15, chronic stress or lifestyle choices might also contribute to reawakening.

Flu infections can force dormant tumour cells to start growing and dividing (green).Credit: Bryan Johnson

For the cells, “it’s an odds game”, says Shelly Peyton, a biomedical engineer at Tufts University in Medford, Massachusetts. Cells are constantly attempting to exit dormancy after small perturbations, only to be killed. “But in moments when the balance is disrupted, that’s when we often see metastasis taking off,” she says.

Peyton’s work focuses on fibrosis, the build-up of fibrous connective tissue at a damaged site. This is often associated with cancer, because stiffness helps the tumour to grow and aids in signalling between cells. But the bone marrow, where dormant cells often reside, is soft, and Peyton is interested in whether that soft environment might be one feature reinforcing dormancy. She says it’s possible that natural, age-related loss of bone density (osteoporosis) or hormonal changes in women who previously had breast cancer could trigger fibrosis, and potentially a reawakening of their cancer.