Study design and participants

Participants were recruited from Samsung Medical Center and Seoul St Mary’s Hospital (Seoul, Korea) between 2012 and 2023 through prospective and retrospective cohorts. Retrospective cases were selected based on the availability of archived primary tumour and matched normal blood samples, along with sufficient clinical information, and were enroled regardless of disease stage or survival status at accrual. All retrospective samples were obtained shortly after diagnosis, typically at curative-intent surgery. Detailed study design, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the CONSORT diagram are provided in Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Fig. 1. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of both institutions (Samsung Medical Center: SMC 2022-05-050 and SMC 2013-04-005; Seoul St Mary’s Hospital: KC21TISI0007 and KC22TISI0292) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Written informed consent, including consent to publish de-identified clinical and genomic data, was obtained from all prospective participants. For retrospective cases, the use and publication of de-identified data were approved by the relevant institutional review boards, with a waiver of informed consent where applicable. A subset of participants was enroled as part of substudy components within the clinical trials NCT03131089 and NCT06334471, which informed specific aspects of the study design.

Sample preparation for sequencing

We performed WGS using CancerVision assay as previously reported58. In brief, WGS was performed on tumour samples obtained as part of routine clinical care either via surgery or biopsy and stored as fresh frozen tissue. For biopsy sample cores were retrieved first for routine pathology, followed by at least one additional core for cancer WGS. Biopsy sample cores were retrieved first for routine pathology, followed by at least one additional core for cancer WGS. For the matched normal samples peripheral blood was used. DNA extraction and library preparation was performed at the Inocras in a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-certified laboratory. We used the Allprep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) for DNA extraction, and TruSeq DNA PCR-Free (Illumina) for library preparation. Sequencing was performed on the Illumina NovaSeq6000 platform (Illumina) with an average depth of coverage of 40x for tumour and 20x for blood. Quality assessment of the WGS data is available in Supplementary Table 10.

For whole-transcriptome sequencing, total RNA was extracted using the AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. Total RNA was quantified using a Qubit Fluorometer (Invitrogen) and the purity and integrity were assessed by the TapeStation RNA ScreenTape (Agilent Technologies). Total RNA-sequencing analysis enabled detection of both coding and noncoding RNA, along with other long intergenic noncoding RNA (lincRNA), small nuclear RNA (snRNA) and small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA). RNA-sequencing libraries were constructed using the KAPA RNA HyperPrep Kit, with RiboErase (Roche Molecular Systems, following the manufacturer’s protocol. We quantified and assessed the libraries using KAPA Library Quantification Kits for Illumina Sequencing platforms according to the qPCR Quantification Protocol Guide (KAPA Biosystems, KK4854) and the TapeStation D1000 ScreenTape (5067–5582, Agilent Technologies) recommendations. The generated libraries were sequenced by using a paired-end 150-bp read protocol on a NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina) with the S4 reagent kit (Illumina).

Genomic analysis and interpretation

Comprehensive genomic analysis and interpretation were conducted using the CancerVision platform (Inocras). WGS data were aligned to the GRCh38 human reference genome using bwa-mem (v.0.7.17-r1188)59. Preprocessing included duplicate marking and generation of compressed reference-oriented alignment map (CRAM) files. Somatic SNVs and short indels were called using Mutect2 (GATK v.4.0) and Strelka2 (v.2.9.10)60,61. High-confidence somatic variants were selected based on the following criteria: ≥2 variant reads in tumour, ≤1 variant read in matched normal, mapping quality ≥15, variant allele frequency (VAF) ≤ 5% in tumour, and population allele frequency ≤1% in the panel of normals.

Tumour purity, ploidy, and segmented CNV profiles were estimated with Sequenza (v.3.0.0)62 and somatic structural variations were identified using Delly (v.0.7.6)63. High-quality structural variations were defined as those with ≥2 variant reads in tumour, ≤1 in normal, mapping quality ≥15, and population allele frequency ≤5% in the panel of normals. GISTIC (v.2.0.23) was applied to identify recurrently amplified or deleted genomic regions64. AmpliconArchitect (v.1.2) was used to detect and characterize ecDNA amplicons42. Variant annotation was performed using the Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor (VEP, release 112)65. Variant call format (VCF) files were processed with bcftools (v.1.9). All variants, both germline and somatic, were subjected to rigorous manual review and curation within Inocras’s proprietary genome browser.

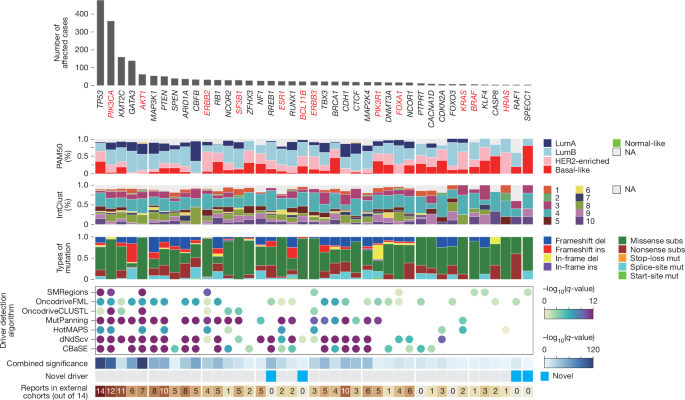

Identification of protein-coding driver genes

Protein-coding driver genes were identified using the IntOGen pipeline (v.2023), which integrates seven independent driver gene identification methods: dNdSCV, OncodriveFML, OncodriveCLUSTL, cBaSE, MutPanning, HotMaps3D and smRegions17. These methods collectively assess the selective advantage of somatic mutations in cancer genomes.

To determine a consensus set of driver genes, we combined the results from the seven methods using a strategy previously described. In brief, for each method, the top 100 ranked genes were selected along with their associated P values and q-values. Somatically mutated genes categorized as tier 1 or tier 2 in the COSMIC Cancer Gene Census (CGC) were used as a reference set of known drivers66. The relative enrichment of CGC genes in the top-ranked gene lists was evaluated to assign a per-method weighting. The final consensus ranking was obtained using Schulze’s voting method, and combined P values were estimated using a weighted Stouffer z-score method.

Candidate driver roles were further classified based on dN/dS ratios for missense (wmis) and nonsense (wnon) mutations, derived from dNdSCV. A distance metric was defined as:

$$\rmDistance=(\rmwmis-\rmwnon)/\sqrt2$$

Candidate drivers with distance >0.1 were considered oncogenes, as they exhibited an excess of missense over nonsense mutations, and candidate drivers with distance <0.1 were classified as tumour suppressor genes, characterized by an excess of nonsense over missense mutations.

Additionally, each candidate driver was annotated based on its presence in any IntOGen cohorts from a previous pan-cancer analysis (Supplementary Table 11).

To ensure accuracy, we manually filtered the significant driver genes (combined q-value <0.10), excluding known artefacts (for example, PABPC1) and genes whose annotated driver roles were inconsistent with prior literature, such as JAK1, VAV2 and HGF.

Mutational signature analysis

We estimated contributions of mutational signatures to an observed mutational spectrum in each sample (the presumed amount of exposure to corresponding mutational processes). We solved the following constrained optimization problem67:

$$\mathrmArgmin_hv-Wh^2$$

where v ∈ Rm×10+, W ∈ Rm×k0+, h ∈ Rk×10+ where R denotes the set of real numbers, m×1 and k×1 indicate real vectors of dimensions m and k, respectively, m×k indicates a real matrix of dimension m by k, and 0+ denotes strictly positive real values (here, m is the number of mutation types and k is the number of mutational signatures). For each sample, given the observed counts of each mutation type v from a sample and the pre-trained mutational signature matrix W, we calculated exposure h. We used the R package pracma, which internally uses an active-set method to solve the above problem. Our method demonstrates comparable performance to SigProfiler68, an elaborated version of the framework used for the previous Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer (COSMIC) compendium of mutational signatures, and SignatureAnalyzer69, which is based on a Bayesian variant of non-negative matrix factorization, in accurately estimating mutational signature contributions (Supplementary Discussion 3).

The relative contributions of mutational signatures were calculated by fitting 16 consensus mutational signatures previously identified in breast cancers (COSMIC signatures SBS1, SBS2, SBS3, SBS5, SBS8, SBS13, SBS17a, SBS17b, SBS18, ID1, ID2, ID3, ID5, ID6, ID8 and ID9; available at https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic/signatures)2. For samples with a cosine similarity below 0.90, a manual review was performed, and additional COSMIC signatures were incorporated for refitting to improve the accuracy of signature decomposition. The additional signatures included those associated with polymerase eta somatic hypermutation activity (SBS9), polymerase epsilon exonuclease domain mutations (SBS10a and SBS10b), platinum chemotherapy treatment (SBS31), defective DNA mismatch repair (SBS21 and SBS44), and activation-induced cytidine deaminase (SBS84), as well as signatures of unknown aetiology (SBS34, SBS41, ID4 and ID11).

HRD and MSI

To assess HRD, we developed our proprietary algorithm by combining HRD-associated features, such as mutational signatures of point mutations, and copy number changes27. These included single-base substitution signatures (SBS3 and SBS8; reference signatures are available at https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/signatures/), an indel signature (ID6), genomic rearrangement signatures (RS3 and RS5), deletions accompanied by microhomology, and CNVs. Custom scripts scaled scores of the multi-dimensional features using coefficients derived from published algorithms to compute the final HRD probability scores. For a quantitative evaluation of somatic microsatellite alterations, we considered both the score from MSIsensor70 and the proportion of microsatellite instability (MSI)-related mutational signatures (SBS6, SBS15, SBS20, SBS21, SBS26, SBS30 and SBS44)2.

Mutation copy numbers and determination of pre- and post-amplification events

We estimated mutation copy number (nmut) using the previously described formula71

$$n_\mathrmmut=f_s\times (1/\rho )\times [\rho \times n^t_\mathrmlocus+n^n_\mathrmlocus\times (1-\rho )]$$

In this formula, fs indicates variant allele fraction, ρ indicates tumour cellularity. nt locus and nn locus are absolute copy numbers in tumour and normal cells, respectively, which were derived from the following formula.

$$n_\mathrmlocus=2\times \mathrmRD_\mathrmlocus/\mathrmRD_\mathrmauto$$

in which RDlocus indicates read depth of the locus of interest, and RDauto indicates average haploid autosomal coverage that was obtained from paired normal WGS.

A mutation was classified as a pre-amplification event, when nmut was larger than the major copy number of tumour multiplied by a factor of 0.75. If nmut was smaller than the above value but larger than 0.75, the mutation was assigned as post-amplification or minor allele mutations.

Molecular within-tumour timing of copy number gains

When a chromosomal segment is gained, it inherently co-amplifies all somatic mutations acquired within the segment up to that point in time, and thus the relative timing of genomic gains can be inferred by comparing frequencies of these co-amplified somatic mutations. To estimate relative event timing within individual tumours we utilized a relative timing measure, π, for every copy gain72,73, which represents the proportion of mutations per unit length of DNA that occurred before the event relative to the total number of mutations on the same DNA interval. Since mutations accumulate over time, this measure can be used to evaluate the timing of a copy number gain in a hypothetical molecular clock. To remove the effect of mutational processes that lead to a hypermutator phenotype (such as APOBEC mutagenesis, MSI and HRD), the number of mutations in each amplified segment was adjusted according to the proportion of SBS1 and SBS5, considering their clock-like nature74,75.

Breast cancer subtyping

We classified breast cancer samples into intrinsic subtypes using the prediction analysis of microarray 50 (PAM50) gene expression profiling method12. After loading gene expression data and removing duplicates and missing values, subtyping was conducted with the molecular.subtyping function from the genefu package76, applying the PAM50 model to classify samples into five categories: luminal A, luminal B, HER2-enriched, basal-like and normal-like.

To classify breast cancer samples into integrative clusters (IntClust) based on their copy number and expression profiles, we utilized the ic10 R package, a validated tool designed for the IntClust subtyping system. This classification method was originally derived from the METABRIC cohort and integrates both gene expression and segmented copy number variation data to define ten molecular subtypes of breast cancer52. The algorithm was run with default parameters, using log2 copy number ratios as input.

Scoring focally amplified genomics regions

To construct the landscape of focal amplifications across the whole genome, we calculated the F-score for each 5-Mb window. For each sample, we identified the segment with the maximum copy number within each window and computed the ratio of this copy number to the segment’s width. We then summed these ratios across all samples to define the F-score. The F-scores were subsequently plotted across the entire genome.

$$\beginarrayl\rmF \mbox- \mathrmscore_\mathrmwindow\\ \,=\,\Sigma _\mathrmall\; samples\max (\mathrmmajor\; copy\; number_\mathrmsegment/\mathrmwidth_\mathrmsegment)_\mathrmwindow\endarray$$

Survival analysis

All tumour samples used for survival analyses were collected prior to the initiation of targeted therapies, ensuring that the results were not influenced by treatment-induced genomic alterations. Survival analyses were conducted using the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences between groups were compared using the log-rank test.

PFS was defined as the time from treatment initiation to disease progression or death from any cause, whichever occurred first. Overall survival (OS) was measured from the time of diagnosis to death from any cause. Disease-free survival was defined as the time from adjuvant treatment initiation to the first documented recurrence or death from any cause, whichever occurred first.

In all survival analyses, both breast cancer-related and unrelated deaths were treated as events.

To evaluate the association between specific variables and survival outcomes, a Cox proportional hazards regression model was applied, with multivariate models incorporating relevant clinical and molecular covariates to adjust for potential confounders.

Given the mixed prospective and retrospective nature of this study, immortality bias (left truncation bias) was carefully addressed: (1) consistent survival definitions: the same survival time definitions were applied uniformly to both retrospective and prospective cohorts; (2) statistical adjustment for cohort type: cohort type (prospective versus retrospective) was included as a covariate in Cox regression models to correct for potential bias; (3) sensitivity analyses: we conducted additional sensitivity analyses, assessing the impact of cohort selection on survival estimates to ensure the robustness of our findings; and (4) external validation: where possible, independent external cohorts were used to validate survival analyses and confirm reproducibility.

These measures minimize potential survival biases, ensuring that our findings accurately reflect the prognostic and predictive significance of genomic alterations (Supplementary Discussion 6).

Statistics and reproducibility

Statistical tests or methods are described in the figure legends. We used R (v.3.4.0) for all data processing and secondary computational analysis.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.