Erika Berenguer, an ecosystems researcher who studies the effects of fire in the Amazon, feels ‘deep sadness’ about the rainforest’s demise.Credit: Marizilda Cruppe/Rede Amazonia Sustentavel

“When I first found out the Amazon forest was becoming a source of carbon emissions a few years ago, I was devastated,” says Luciana Gatti, a climate scientist at Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research in São José dos Campos. Because it has been depleted, the rainforest is not as efficient as a carbon sink as it used to be. Gatti watches the ongoing destruction of the forest and its impact on climate change with sadness and extreme worry. “It’s a hard scenario that makes me anguished, because the window for us to do something is closing,” she continues.

Many climate scientists and professionals face eco-anxiety in their daily work — an issue that is on the rise and is worsening mental-health disorders in the general population. Young adults are particularly affected. In a 2021 survey of 10,000 people aged between 16 and 25 years old in 10 countries, almost half said that climate distress affected their ability to sleep and work (C. Hickman et al. Lancet Planet. Health 5, e863–e873; 2021).

I’m a climate scientist. Here’s how I’m handling climate grief

There is a growing body of research around the intersection of climate change and mental health — but climate scientists’ well-being rarely comes under the microscope (Nature Mental Health 2, 119–120; 2024). When it does, the results are stark. For instance, only 6% of 380 lead authors and review editors for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) think that the 1.5 °C warming limit set by the 2015 Paris climate agreement can be achieved, according to a May survey by UK newspaper The Guardian. Most said they felt distress and frustration over how the climate crisis is being handled worldwide.

“Climate researchers are grappling every single day with important information,” says Robin Cooper, a member of the steering committee at the Climate Psychiatry Alliance, an independent group of psychiatrists and mental-health professionals, who is based in San Francisco, California. “And if they allow themselves to tolerate the feelings they are going through, they will need to manage the implications of what their science is showing them. That’s a big, big intrusive stress.” Cooper considers the stress that climate scientists face to be similar to that which affects first responders in climate disasters. “They are a vulnerable population, a group that is exposed in very serious ways to the reality of climate change,” she says.

Such exposure can be damaging in the long run. Stress is an essential survival mechanism in response to acute risk — but constant exposure takes its toll on physical and mental health. The continuous activation of stress hormones can contribute to conditions ranging from high blood pressure to depression and addiction. Cooper says that humans cannot absorb the long-term, sustained threats of environmental disasters. Climate stress and anxiety are more persistent and more chronic than are other stressors that humans experience, Cooper says. “And that is not the way our biology is wired.”

Grieving process

Erika Berenguer, an ecosystems researcher at the University of Oxford, UK, has felt the consequences of this insidious burden. She studies the effects of fire on trees in the Amazon and finds it difficult to witness the rainforest’s decline. “The first time I felt deep sadness was in 2015, when about one million hectares of forest got wiped out by fire. In the field, I went to sleep each night and woke up each morning shrouded in smoke and ashes from the corpses of a dying forest,” she says. Once back home, a colleague told her that she was experiencing grief for the forest. “The feeling hasn’t gone away since then,” she adds.

After her most recent fieldwork season, in November 2023, after a record number of fires that October, Berenguer’s stress led to physical symptoms. At first, she had itchy blisters on her feet. Then she had to be treated for gastroparesis, a condition that affects the movement of the stomach and intestinal muscles, causing nausea and vomiting.

Heeding the happiness call: why academia needs to take faculty mental health more seriously

Exercising by rowing helps Berenguer to clear her head, but it doesn’t bring long-term relief. “Burnt forests tell the story of a past that is no more, and of an unfortunate future for most of the Amazon. It’s profoundly painful not to be able to change it,” she says.

Detaching from the problem is not an option. “Scientists have to bear witness to the loss of ecosystems, measure the impact of destruction and natural recovery — and we’re responsible for proposing some solutions to the problem as well. We have to be there,” she declares.

Berenguer notes, however, that the risk-assessment forms that researchers fill in before going into the field cover only physical hazards, not mental health. “Who is going to protect us from seeing the world’s largest rainforest burn?” she asks.

Fieldwork insurance “doesn’t cover psychotherapy, and this is something climate and Earth scientists need to have a serious discussion about”, she adds.

Managing emotions

The fallout from being on chronic high alert might need more than conventional talking therapies, because not every therapist will know how best to approach climate anxiety. To tackle that gap, Cooper says, the Climate Psychiatry Alliance has joined forces with a similar group, the Climate Psychology Alliance North America, to develop a climate-awareness training programme for therapists. It is also raising awareness of climate anxiety and grief among members of the American Psychiatric Association, which is based in Washington DC.

One approach that can especially benefit scientists, Cooper says, is group discussions, which enable them to feel safe to share their thoughts and feelings and can help them to realize they are not alone. “The culture of scientists doesn’t lean towards collectivity and doesn’t create space for them to share what they’re experiencing,” she adds.

Kristan Childs, a therapist in Sebastopol, California, agrees. “They need permission to feel,” she observes. “Some think if they allow themselves to feel, it’ll be like falling into a pit of despair they can never get out of. But almost always, the opposite happens,” she says. “When they see other people feeling the same way, it actually lifts the burden of aloneness.” And some even feel inspired to take collective action, she says.

Childs, who focuses on ecological distress and community resilience in her work, is a facilitator at the Good Grief Network, a US non-profit organization that runs support groups for people experiencing climate grief and anxiety. At the end of 2023 and earlier this year, she worked with a group of climate professionals. “It’s not about trying to cheer people up,” she says. “It’s about making space for them to share their feelings about how they perceive the impacts of climate change.”

Susanne Moser founded the Adaptive Mind project to help scientists focus on personal restoration techniques to process their emotions.Credit: Courtesy of Susanne Moser, photo by Sarah Watson

Liz Cunningham, a conservation writer based in Rockport, Maine, attended last year’s workshop in search of strategies to navigate the climate crisis. “Over the past year-and-a-half, I had been waking up in the middle of the night, thinking about how all of this is going to unfold,” she says. The workshop helped her to reframe self-care methods — such as meditation and practising gratitude — and to rethink the focus of her writing. Witnessing other participants’ experiences, she says, created space for “grounding, nurturing and stepping back to start to see our lives differently”.

Climate researchers need to process their emotions so that those feelings become bearable and manageable, Childs says. Otherwise, numbing anxiety could stymie a researcher’s ability to do their work.

Motivating force

Peter Kalmus, a data and climate scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, knows that feeling all too well. He made the headlines in 2022 after being arrested for chaining himself to the entrance of a JP Morgan Chase building in Los Angeles, California, to protest against the bank’s investments in fossil-fuel projects. He has also taken part in other climate-related protests. Climate anxiety and climate grief, for him, are different things. “Climate anxiety makes me feel miserable and makes it hard to get work done, and it also gets me physically sick,” he says. Climate grief, by contrast, works for him as a motivator. “I might cry over the imminent loss of the Amazon rainforest, or when I think about how unnecessary this all is, and what it means for my children’s future,” he says. “But climate grief connects me to why I’m doing this.”

Science careers and mental health

Through Scientist Rebellion, an international collective of researchers who demand effective climate action, Kalmus found a way to grieve and act. Climate grief and anxiety, he says, can be processed better when people band together. “All of the scientists who are engaging in activism are talking about their emotions and processing them together.”

By contrast, he thinks that societal fear is making people dissociate from the reality of climate change, because it is too hard to handle — and those who benefit from the status quo use that fear and numbness to delay mitigation actions. Kalmus asks how so many leaders of democracies can ignore science and approve the use of more fossil fuels. “I don’t understand it.”

This open-to-emotions approach has much potential when it comes to helping scientists, says Susanne Moser, a research scholar in environmental studies at Antioch University New England in Keene, New Hampshire. Trained as a geographer and now focused on the intersection of social sciences and solutions for the climate crisis, she helps climate-change professionals on the front lines to build up their psychological resilience. To do so, Moser, who is based in Hadley, Massachusetts, founded the Adaptive Mind project. The organization helps individual scientists and groups to focus on personal restoration and to process trauma, enabling transformative change.

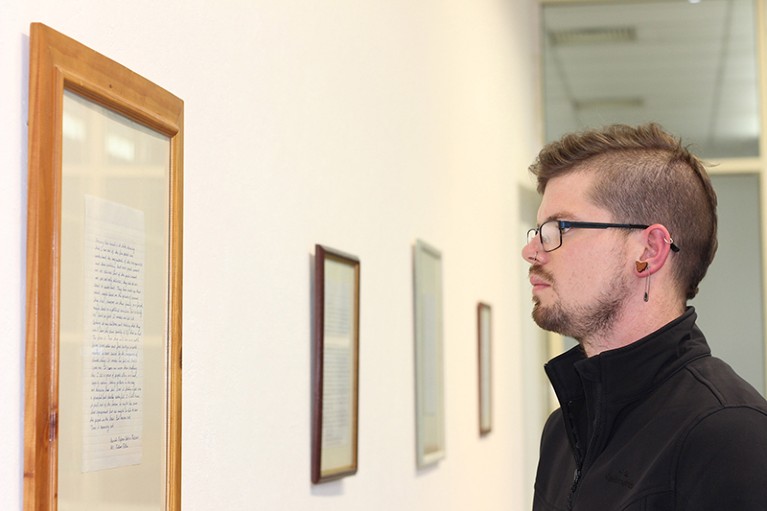

Joe Duggan at the first physical exhibition of his ‘Is This How You Feel?’ letters in 2014.Credit: Joe Duggan

Scientists can be unembarrassed about expressing feelings in their personal lives, but when it comes to climate change, sometimes “they can use their profession as a girdle not to deal with emotions”, she says. “It’s important for people to know,” she continues, “that just because they have an emotion doesn’t mean they can no longer think analytically or systematically through a problem.”

Joe Duggan, a PhD student in science communication at the Australian National University in Canberra, wanted to convey a similar message through his science-awareness project ‘Is This How You Feel?’. He created it in 2014 as a master’s student at the university to connect people outside academia with the human face of climate-change research. He asked scientists to answer the question ‘How does climate change make you feel?’ in handwritten letters that he posted on the project’s website.

The idea was to pull scientists away from their computers, routines and jargon to share their emotions. Leading names in the field responded, including Johan Rockström at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany and Michael Mann at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. The project has gathered 50 letters so far, and Duggan invited 23 of the researchers who originally responded to weigh in on the situation 5 years later. “I think most of them felt like they were smashing their heads against a brick wall,” Duggan says. Still, there was also some space for hope. “Hope of two kinds,” he says. “One is a wishful hope, the sort of ‘I have hope because that’s all I can do’ and the other is a more logical one, hung on stories of [climate activist] Greta Thunberg and people standing up and fighting for systemic change.”

Possibilities for change

According to those interviewed for this article, there’s still a long way to go for research institutions to adequately address the mental-health challenges caused by eco-anxiety and the climate crisis. But some initiatives are starting to take root. In the University of California (UC) system, researchers — mainly from health and environmental fields — have joined together to develop a resilience course aimed at undergraduate and graduate students on all ten campuses, with six currently participating. Jyoti Mishra, a psychiatry researcher at UC San Diego, is co-director of the course, which held its first classes between April and June. Mishra studies the impact of wildfires on mental health and jumped at the course idea when her colleague Elissa Epel, a psychiatry researcher at UC San Francisco, proposed it.

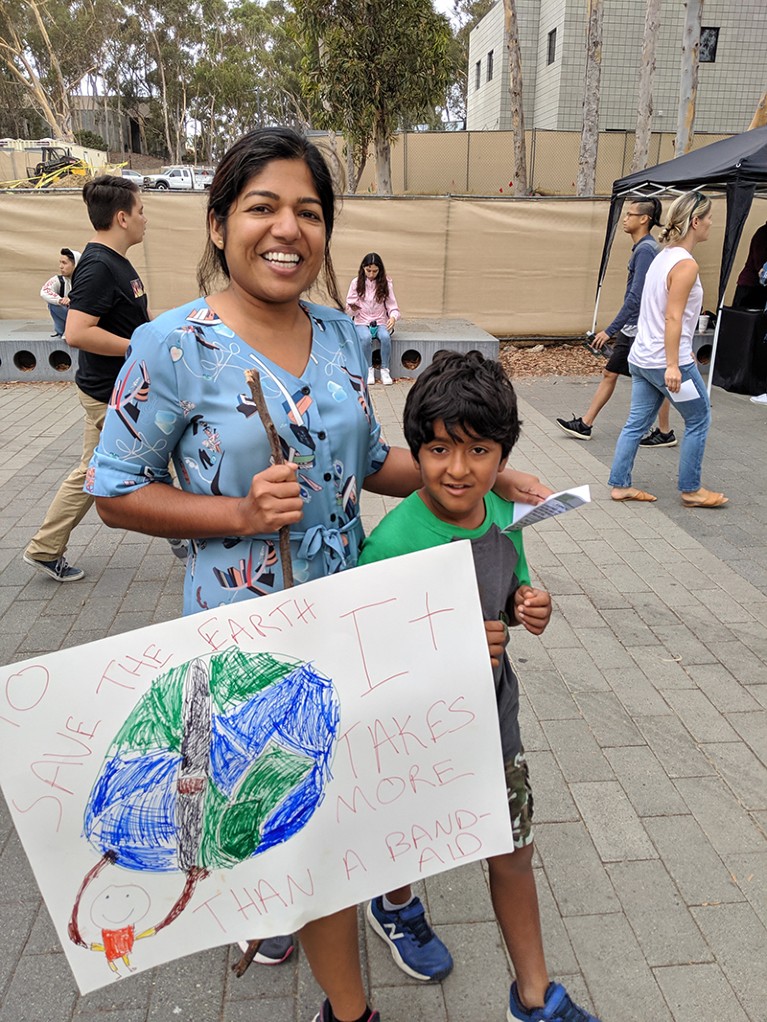

Jyoti Mishra (left, with son) co-directs a climate-resilience course in the University of California system.Credit: Jyoti Mishra

“I felt very inspired by what our wildfire-impacted communities in California are doing — people affected by fire come up with solutions, actions and disaster preparedness,” says Mishra. She says the course was modelled on the ecotherapy programme at California State University, Chico, which guides participants through an immersive experience in natural settings with a focus on mental well-being.

“We wanted to create an empowering space for our students as well,” she adds. Participants listen to climate leaders speak about what spurred them into action, learn how to process emotions and thoughts about the climate crisis collectively and receive mindfulness training. At the end, students put their skills to work in a practical project.

“Projects varied a lot,” Mishra says, ranging from looking at the impact of fast fashion to thinking about sustainable practices on campuses, such as meat-free days in cafeterias. Others looked at agricultural questions, such as how to manage invasive species and how to create knowledge about generating more indigenous biodiversity.

Climate researchers who receive resilience training from the start of their careers will be better equipped to deal with climate anxiety. According to Mishra, the aim is not to have adults who are better adjusted to a world in collapse, but to arm them to make “a collective change in their interactions with the environment, to make a difference”.

In the current generation of scientists, Gatti had to learn how to shift her mindset in her daily practice to avoid burnout. Similarly to Kalmus, she uses climate grief as a fuel to keep sounding the alarm. “The least I can do is to make noise and learn to speak a language everyone understands — so they become conscious that we must change at the micro and macro levels,” she says. “This is a huge opportunity for humanity to evolve.”