A protester in Brazil calls for ‘climate justice now’. Their government is taking legal action for compensation for harms caused by illegal deforestation.Credit: Adriano Machado/Reuters

It bears repeating over and over: the science is not in question. High concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere are warming the planet. International law is also clear: under the legally binding Paris climate agreement, nations pledged to keep average temperatures within 1.5 °C of pre-industrial levels. And yet, as emissions continue to increase, global temperature rises will almost certainly exceed this limit.

The research community is frustrated that its warnings are not being heeded. What is the point of a legally binding agreement if countries can effectively ignore it? Some scientists are arguing that climate researchers need to become climate activists, too1,2. But others, and more than a few governments, are not giving up on the legal route. Because the Paris agreement lacks an enforcement mechanism, they want courts to ensure that all those with climate responsibility — nationally and internationally — can be held to their promises. And they have been busy going to court.

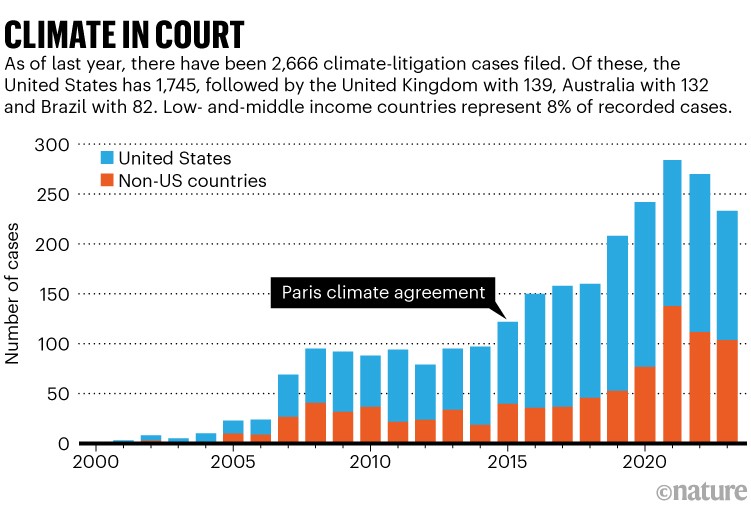

By the end of last year, 2,666 climate-litigation cases had been filed worldwide, according to a report3 by the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, published in June (see ‘Climate in court’). Most claimants are individuals, young and old, as well as non-governmental organizations (NGOs). All are looking to hold governments and companies accountable for their climate pledges. In 2022, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change4 acknowledged that, if successful, climate litigation “can lead to an increase in a country’s overall ambition to tackle climate change”. Note the phrase, “if successful”.

Source: Grantham Research Institute, London School of Economics/Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, Columbia Law School

There have been a handful of landmark judgments. For example, in May, courts in Germany and the United Kingdom separately found that their government’s policies would fail to meet emissions-reduction targets that are set out in law. But most claimants struggle to get a positive result, as Joana Setzer and Catherine Higham, researchers at the Grantham Institute in London, show in their report3. Much climate litigation is mired in a maze of process and procedure. In some instances, respondents — mostly corporations — are embarking on counter-litigation, essentially challenging climate laws that they do not like.

This is where the entry of the world’s highest court could be a game changer. In the next few months, the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the United Nations’ principal judicial organ in The Hague, the Netherlands, will begin hearing evidence on two broad questions: first, what are countries’ obligations in international law to protect the climate system from anthropogenic greenhouse-gas emissions, and second, what should the legal consequences be for states when their actions — or failure to act — cause harm?

The time to act is now: the world’s highest court must weigh in strongly on climate and nature

This could be one of the most consequential developments in climate policy since the Paris agreement itself. Adil Najam, president of the global conservation NGO WWF, writes in a World View that the ICJ’s opinion “will amplify the voices of millions of scientists and citizens who are demanding strong ambition and action on climate and nature protection”.

These voices include people arguing against greenwashing, or for the protection from climate change as a human right, as well as public authorities seeking compensation from corporations for climate-related harms, under the ‘polluter pays’ principle. Last September, California launched legal action against five of the world’s largest oil companies — BP, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, Exxon and Shell — and their subsidiaries, demanding that they pay “for the costs of their impacts to the environment, human health and Californians’ livelihoods, and to help protect the state against the harms that climate change will cause in years to come”.

Brazil’s public prosecutor’s office and the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources are seeking compensation for harms specifically from greenhouse-gas emissions caused by illegal deforestation5. The ICJ’s opinion, although non-binding, will be especially important for low- and middle-income countries, which have comparatively less access to expertise in climate science, policy and law than do high-income countries.

Courting concerns

One criticism of climate litigation states that courts should not be getting involved in what are essentially political processes. The argument is that, if climate laws lack an enforcement mechanism, then governments need to legislate for one. According to this idea, it shouldn’t be up to the courts to do something that is the job of governments; that would be judicial overreach.

Courts are well aware of these concerns, and the ICJ will be, too. Legal redress is but one tool in a larger toolbox of actions. Ultimately, climate action at scale and pace will happen only when the international community is persuaded that humanity has no alternative but to decarbonize in a just way; not because of the threat of prosecutions, but because our collective survival depends on it.

But the law has a key role. And the ICJ’s opinion, backed by the highest standards of evidence, will be necessary in clarifying states’ responsibility for climate harms and their obligation to protect the environment from emissions.