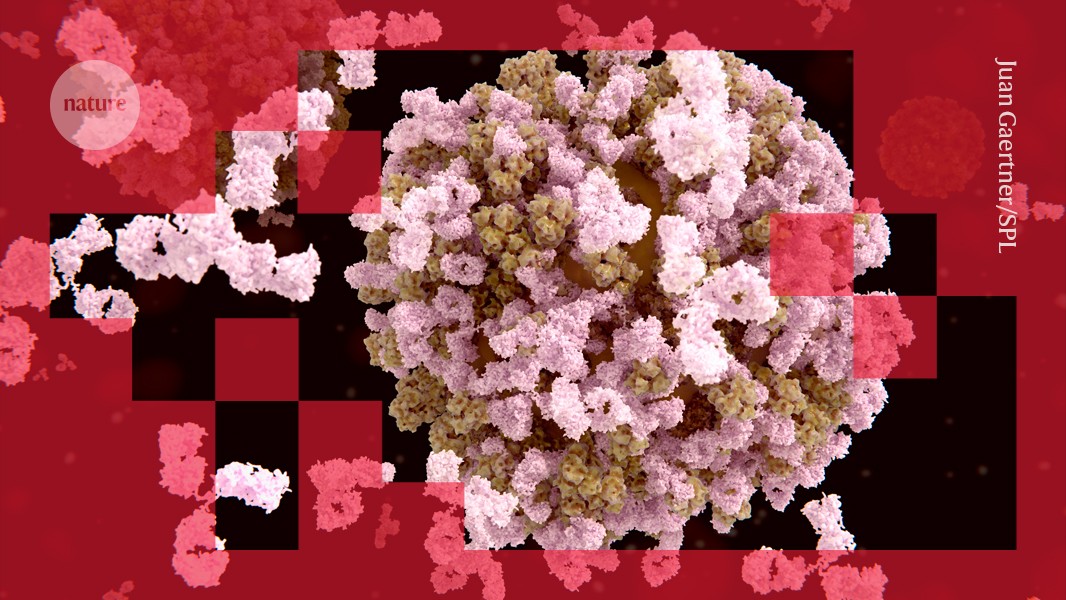

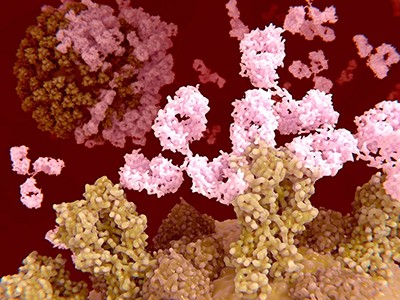

An illustration of antibodies (pink) binding to a flu virus (brown).Credit: Juan Gaertner/Science Photo Library

Biologists achieved a landmark in protein design last year: using artificial intelligence (AI) to draw up entirely new antibody molecules1. Yet the proof-of-principle designs lacked the potency and other key features of commercial antibody drugs that rack up tens of billions in annual sales.

After a year of progress, scientists say they are on the cusp of turning AI-designed antibodies into potential therapies. In recent weeks, numerous teams have reported successfully using proprietary commercial AI tools and open-source models to make antibodies that have properties of antibody drugs.

‘A landmark moment’: scientists use AI to design antibodies from scratch

“These latest efforts are remarkably powerful advances that enable a democratization of antibody engineering,” says Chang Liu, a synthetic biologist at University of California, Irvine.

The latest wave of success with de novo antibody design “will have a big impact on how quickly and how many de novo therapeutics we will see in clinical trials”, adds Timothy Jenkins, a protein engineer at the Technical University of Denmark in Kongens Lyngby.

Precision nanobodies

Therapeutic antibodies are usually made by screening vast numbers of diverse antibodies to find ones that can recognize a certain target. But sometimes, these screens turn up only antibodies that bind weakly to the target or recognize the wrong region on it.

“There isn’t much precision,” says Surge Biswas, chief executive of antibody-design company Nabla Bio in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Instead, scientists hope to specify an antibody’s desired target — the active site of an enzyme implicated in disease, for instance — and have an AI model suggest designs. “The promise of AI-guided design is that you can be atomically precise,” Biswas adds.

AlphaFold is five years old — these charts show how it revolutionized science

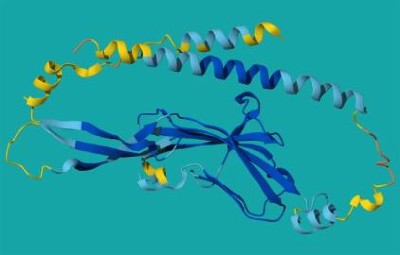

Antibodies — immune proteins that recognize foreign molecules, such as those made by pathogens, with exquisite specificity — have been a challenge for AI to design. AI models such as AlphaFold have struggled to predict the shape of flexible loop regions of antibodies, which they use to recognize their targets.

But new tools developed in the past year — including an updated version of AlphaFold — have proven better at modelling these flexible regions, says Gabriele Corso, a machine-learning scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. Progress in antibody design has followed.

In October, Corso and his colleagues described the BoltzGen model in a preprint2, showing that it can adroitly design ‘nanobodies’ — small, simple antibodies resembling molecules made by sharks and camels — against proteins implicated in cancer, viral and bacterial infections and other diseases. In most cases, the researchers identified antibodies with strong target binding after expressing just 15 of the most-promising designs in cells and testing them in laboratory experiments. However, the molecules were not tested in disease models.

Other teams are making similar progress. For instance, a team at Stanford University in California and the Arc Institute in Palo Alto, California, has also released a model that can design nanobodies with high efficiencies3. And last month, the team behind the 2024 breakthrough — led by Nobel-prizewinning biophysicist David Baker at the University of Washington in Seattle — reported in Nature4 marked improvements in their nanobody design efforts, using another open-source tool.

Full length antibodies

The boldest claims in AI antibody design come from companies working on the challenge. Last month, scientists at Nabla and Chai Discovery in San Francisco, California, said they had made ‘drug-like’ antibodies using AI tools.

Both teams said that, in addition to nanobodies, which are composed of a single chain of amino acids, they had generated full-length antibodies. Baker’s team reported such designs in their report as well4. Lab experiments showed that some of the designer molecules recognized diverse disease targets — including molecules called G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), which have challenged conventional antibody design efforts — at potencies similar to those of commercial antibody drugs. They also boasted useful properties that can make or break drug candidates, such as the capacity to be produced at high levels and to recognize only their intended targets5.