Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every day? Sign up here.

Source: Ref.1Source: Ref. 1

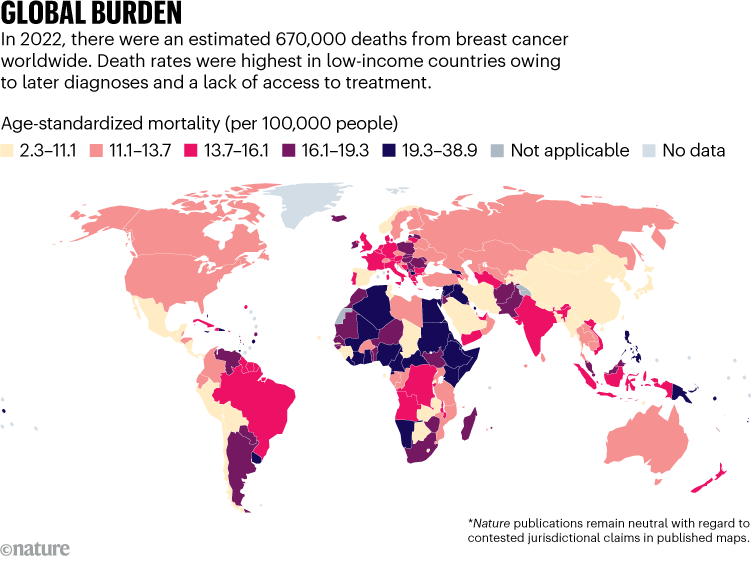

People in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) face higher death rates from breast cancer than those in wealthier nations, because of a lack of screening and treatment options. For example, people aged under 50 in low-income countries are four times more likely to die from breast cancer than those in high-income countries, on the basis of the most-recent available data, from 2022. Because of increasing life expectancy and changing prevalence of risk factors — such as obesity, drinking alcohol, and less breastfeeding — breast cancer cases and deaths are predicted to rise over the next 25 years, with the greatest increase in LMICs.

Reference: Nature Medicine paper

Through actions such as firing of US federal scientists en masse, blocking clean-energy incentives and abandoning international climate commitments, the administration of US president Donald Trump is hobbling the country’s efforts to reduce its contribution to global warming. As courts start to assess the legality of some of Trump’s policies, the uncertainty is hampering climate- and energy-related programmes and businesses. “There’s been a viciousness that I hadn’t anticipated in tearing everything down without a coherent plan for what to build back up,” says atmospheric scientist Daniel Cohan.

Meanwhile, a coalition of nonprofit groups, archivists and researchers are working to ensure that the federal environmental data they rely on remains available to the public. Research librarian Alejandro Paz and policy scholar Eric Nost, who belong to the Public Environmental Data Partners network, have written an overview of where US government data is disappearing, how to find it and how to save it.

Politico | 10 min read & The Conversation | 6 min read

Do you know your reef from your thief and your granny from your grief? Scouts and seafarers will know that these are similar-looking knots, and the reef is strongest. “The grief knot, aptly named, is so weak you could sneeze on it and it would fall apart,” notes brain scientist Sholei Croom. But people aren’t that good at guessing which knot is stronger just by looking at them — even when they showed a good understanding of the underlying structure. This blindspot in physical reasoning sheds light on how our brains perceive the world, say researchers.

Scientific American | 4 min read (before you read, jump to the image to take the test yourself)

Features & opinion

Iron particles in an oil drop on a glass slide respond to magnets placed underneath.Credit: Felice Frankel

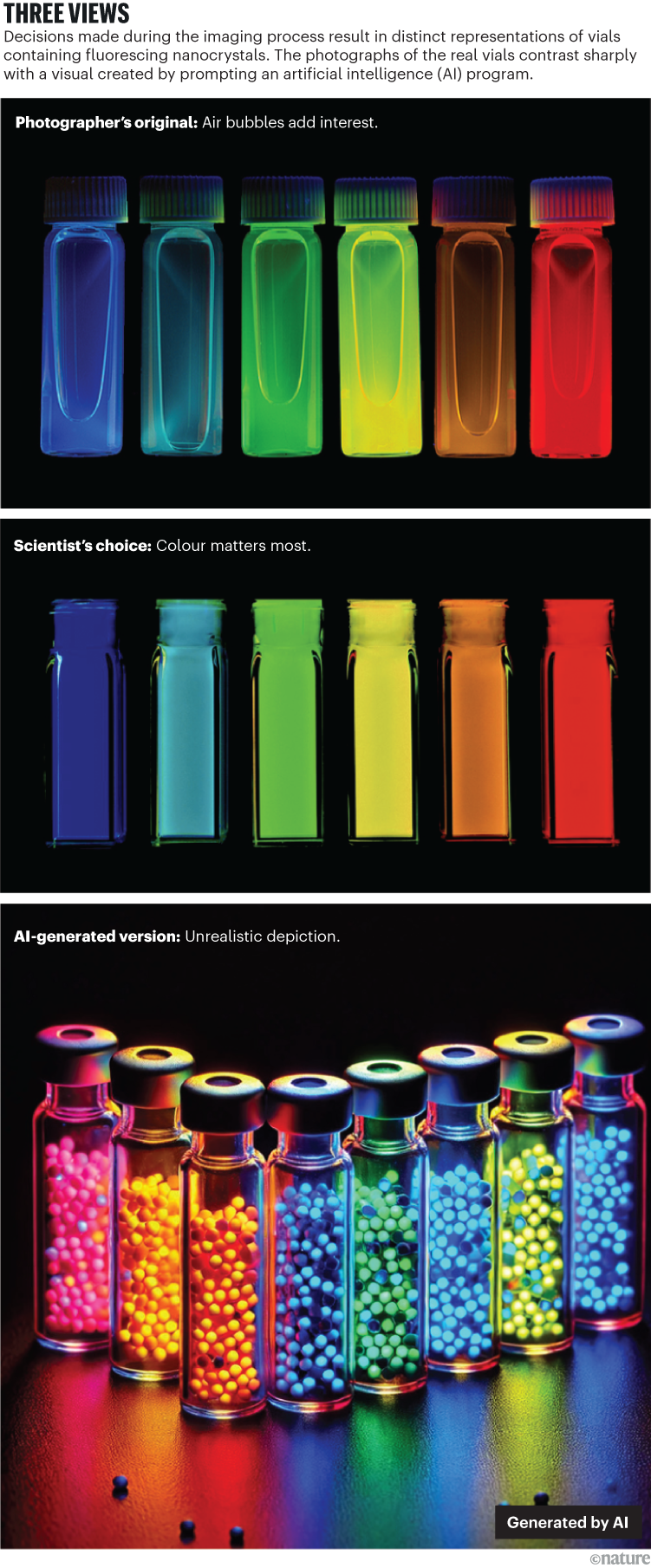

“The joy of being a science photographer is that I must learn about the things I am documenting to produce communicative and trustworthy images,” writes Felice Frankel. In an exploration of what AI-generated images might mean for science, Frankel touches on the difference between illustration and documentation, the ethics of manipulating images and the need for scientists to undergo visual-communication training. “It is clear that genAI images are part of our future,” says Frankel, but we need guidelines to ensure data are faithfully represented.

Credit: Felice Frankel

Communication is a powerful tool for driving climate action, but it’s often overlooked by researchers, says ecologist Harini Nagendra. Engaging storytelling that celebrates the joy of nature, rather than simply presenting scientific information, can make climate science more relatable to the public. These stories must be accessible in as many languages as possible, and elevate the knowledge of Indigenous communities. “We must share the stage with others affected by climate change, to help us understand how it feels,” Nagendra writes.

Researchers have been eavesdropping on unusually close-knit families of carrion crows (corvus corone corone) in Spain, collecting data on hundreds of thousands of different vocalizations. Small microphones recorded a variety of soft calls, far quieter than the familiar ‘caws’. The team then used AI to analyse and group the sounds. The researchers aim to better understand how the crows cooperate — and experiment with some human-crow chats.

On Friday, Leif Penguinson was scaling a sandstone cliff face in the Waterberg Plateau National Park, Namibia. Did you find the penguin? When you’re ready, here’s the answer.

If you enjoy this newsletter, I’d be very grateful if you were to recommend it to a friend or colleague. Please click here to forward it by e-mail. Thank you!

Thanks for reading,

Flora Graham, senior editor, Nature Briefing

With contributions by Jacob Smith

Want more? Sign up to our other free Nature Briefing newsletters:

• Nature Briefing: Careers — insights, advice and award-winning journalism to help you optimize your working life

• Nature Briefing: Microbiology — the most abundant living entities on our planet — microorganisms — and the role they play in health, the environment and food systems

• Nature Briefing: Anthropocene — climate change, biodiversity, sustainability and geoengineering

• Nature Briefing: AI & Robotics — 100% written by humans, of course

• Nature Briefing: Cancer — a weekly newsletter written with cancer researchers in mind

• Nature Briefing: Translational Research — covers biotechnology, drug discovery and pharma