COP30 left many countries disappointed because no new road maps were created to help nations transition away from fossil fuels.Credit: Wagner Meier/Getty

Ten years after the Paris agreement was adopted, world leaders left the United Nations COP30 climate summit in Belém, Brazil, with an outcome that kept the process alive but does little to stave off the perils of global warming. Many scientists walked away dismayed and disappointed.

Despite years of commitments and research that have laid the groundwork for action, the climate summit of achieved “essentially nothing”, says Johan Rockström, director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany.

But, there were some signs of hope that multilateralism can tackle climate change. Over the course of two weeks, representatives from nearly 200 governments worked through hot days, long nights, a fire in the venue and numerous protests — including by Indigenous groups and others fighting for the protection of the Amazon and other tropical forests.

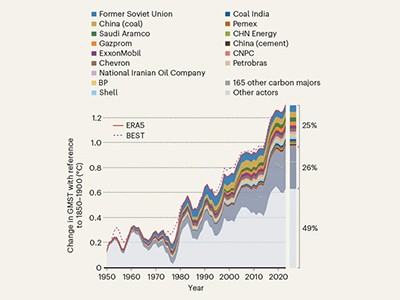

Heatwaves linked to emissions of individual fossil-fuel and cement producers

In the end, governments agreed to a package of measures that pushes forward discussions on financial aid and a new ‘just transition’ mechanism designed to ensure a fair and equitable shift from fossil fuels to clean energy. A glaring omission was language calling for the creation of road maps to phase out fossil fuels and halt deforestation, but Brazil has announced it will push those ideas forward independently of the COP process.

Here, Nature takes a look at the results from COP30 and what comes next.

Sidestepping fossil fuels

The summit failed to deliver major new pledges to curb greenhouse-gas emissions. Out of the 194 entities and countries that sent representatives to COP30, roughly 80 didn’t submit new commitments for 2035, as required under the accord, and the rest submitted weak pledges that are unlikely to alter global trajectory. As a result, scientists with the Climate Action Tracker consortium still project that the world is on track for upwards of 2.6 ° C of warming by 2100.

“The new commitments don’t even move the needle,” says Niklas Höhne, a climate-policy researcher at the NewClimate Institute, an environmental think tank based in Berlin. “It’s really a sign that countries have limited appetite to support something more ambitious on climate.”

Fossil fuels took centre stage briefly. More than 80 countries joined Brazil’s President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in the call for the creation of a road map to phase out fossil fuels, but the proposal ultimately foundered after reported opposition from oil-producing nations including Saudi Arabia and others.

But the idea isn’t dead yet. Brazil promised to push forwards with it independently of the COP process, while the governments of Colombia and the Netherlands announced that they would host the first global conference on the just transition away from fossil fuels in April next year.

Protesters carrying signs that read “our forests are not for sale” broke through security lines of the COP30 climate talks on 12 November.Credit: Pablo Porciuncula/AFP via Getty

Financing climate action

One of the largest disputes at the summit was who should pay for climate action and help developing nations to prepare for and adapt to the unavoidable impacts of global warming. Progress was made: wealthier nations committed to tripling the amount of money they provide to help low-income countries tackle global warming — to US$300 billion annually by 2035. The agreement also carries forward a broader goal of boosting the total to $1.3 trillion annually from all sources, including private investments.

But questions remain about how this will be financed. Previous deals on climate action have been plagued by delays in achieving financial goals as well as by disagreements about how much money should come from publicly funded grants, as opposed to loans and private investments.

China pledges to cut emissions by 2035: what does that mean for the climate?

The final deal at COP30 lays out a process to clarify these issues over the next two years. It’s a step towards ensuring that wealthy countries meet their responsibilities to provide climate finance to those in need, says Jodi-Ann Wang, who researches equity and climate finance at the London School of Economics and Political Science.