Scientists are trying to measure the impact on global health of funding cuts by the United States’ administration. Credit: Luis Tato/AFP via Getty

The United States spent roughly US$12 billion on global health in 2024. Without that yearly spending, roughly 25 million people could die in the next 15 years, according to models that have estimated the impact of such cuts on programmes for tuberculosis, HIV, family planning and maternal and child health.

The United States has long been the largest donor for health initiatives in poor countries, accounting for almost one-quarter of all global health assistance from donors. These investments have contributed to consistent public-health gains for more than a decade. HIV deaths, for example, dropped by 51% globally between 2010 and 2023, and deaths owing to tuberculosis dropped by 23% between 2015 and 2023.

But the administration of US President Donald Trump has cut billions of dollars of spending for global health, including dismantling the US Agency for International Development (USAID) and freezing foreign-aid contributions — some of which has been temporarily restored.

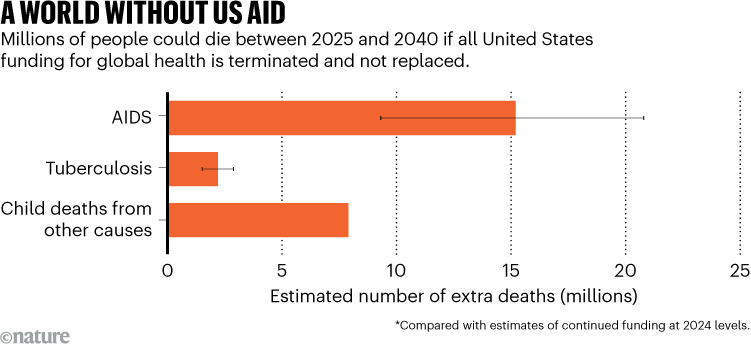

Researchers have been trying to study the potential impact of the funding cuts. John Stover, an infectious-diseases modeller at Avenir Health, a global-health organization in Glastonbury, Connecticut, and his colleagues used mathematical models to estimate health outcomes, should all US funding for global health be cut and not replaced, compared with outcomes if funding provided in 2024 were to continue through to 2040. The results were posted on the preprint server SSRN earlier this month and have not been peer-reviewed1.

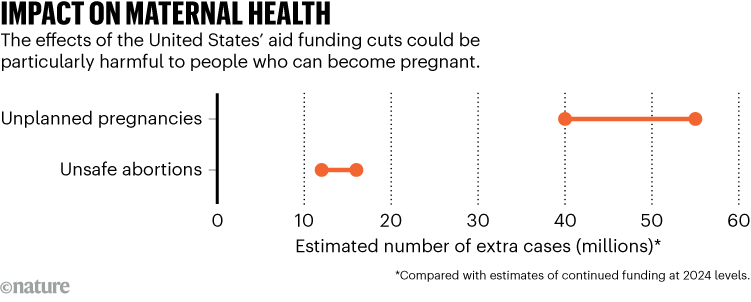

Source: Stover/Preprints with The Lancet

The researchers “use a combination of robust, well-established and proven mathematical models and analytical approaches to estimate the impact”, says Andrew Vallely, a clinical epidemiologist at the Kirby Institute, University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia. “Their findings are devastating to read” and “a wake-up call for all of us working in global health.”

James Trauer, an infectious-disease modeller at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, adds: “These models are probably as good as we have available at the moment for predicting the direct effects of the funding cuts on these various programmes.”

On 28 March, Marco Rubio, the US secretary of state, said that the government was reorienting its foreign-assistance programmes to align with the country’s priorities. “We are continuing essential life-saving programs and making strategic investments that strengthen our partners and our own country.”

HIV and AIDS

The researchers modelled the impact of cutting the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) in the 55 countries it supports, including stopping the delivery of treatments, tests and interventions that prevent transmission. The programme has been affected by funding freezes.

Without PEPFAR, there would be 15 million extra deaths from AIDS by 2040 than if the programme continued (see ‘A world without US aid’). More than 60% of those deaths would take place in six African countries, including Mozambique, Nigeria and Uganda. Roughly 14 million more children would become orphans as a result of those AIDS deaths — a trend that had been expected to decrease over the next 15 years. And 26 million more people could become infected with HIV without PEPFAR.

Source: Stover/Preprints with The Lancet

The impact varies considerably depending on how reliant a country is on US government support, says Stover. In Uganda, for example, 65% of its funding for HIV research comes from the United States, he says. Some models estimated the effects of a partial-funding scenario; in this case, continuing funding for only treatment could avert 97% of the extra deaths and 90% of the extra new HIV infections.

Tuberculosis

The global number of infections of Mycobacterium tuberculosis — the bacteria that causes the world’s deadliest infectious disease — is also expected to ramp up without US aid funding. Researchers looked at the impact of cuts to USAID and US contributions to the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria across 79 low- and middle-income countries — although it is not yet clear by how much US contributions to the fund will shrink in the coming years. These would contribute to 69 million more M. tuberculosis infections and 2 million more deaths by 2040.

These estimates are broadly consistent with other efforts to assess the impact, says Trauer.

“There’s been tremendous progress made in global health over the last couple of decades and we’re at risk of losing a lot of that,” says Katherine Horton, an epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, who contributed to the modelling on tuberculosis.