As anyone seeking to lose weight knows, diets come in and out of fashion. The Sexy Pineapple diet, launched by a Danish psychologist in 1970, never really took off. Kellogg’s no longer promotes the Special K diet, which swaps out two meals a day for a bowl of the breakfast cereal of that name. These days, you don’t hear much about eating according to blood type, cutting out acidic foods or following the potato diet.

Intermittent fasting has, however, had unusual staying power for more than a decade — and has grown even more popular in the past few years. One survey1 found that almost one in eight adults in the United States had tried it in 2023.

The surprising cause of fasting’s regenerative powers

The enduring popularity of intermittent fasting has been fed by celebrity endorsements, news coverage and a growing number of books, including several written by researchers in the field. More than 100 clinical trials in the past decade suggest that it is an effective strategy for weight loss. And weight loss generally comes with related health improvements, including a reduced risk of heart disease and diabetes. What is less clear is whether there are distinct benefits that come from limiting food intake to particular windows of time. Does it protect against neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, enhance cognitive function, suppress tumours and even extend lifespan? Or are there no benefits apart from those related to cutting back on calories? And what are the potential risks?

Neuroscientist Mark Mattson at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland, and author of the 2022 book The Intermittent Fasting Revolution, has been studying fasting for 30 years. He argues that, because ancient humans went for long periods without food as hunter-gatherers, we have evolved to benefit from taking breaks from eating. “We’re adapted to function very well, perhaps optimally, in a fasted state,” he says.

Fasting’s deep roots

Fasting is far from new. Periodic abstentions from food have long been practised in many religions. In the fifth century bc, the Greek physician and philosopher Hippocrates prescribed it for a range of medical conditions.

Recent scientific interest in fasting has its roots in questions raised by research on calorie restriction. Since the 1930s, studies have shown that putting rodents on low-calorie diets can increase their lifespans. Hypotheses proposed to explain this effect include that calorie restriction slows growth, lowers fat intake or reduces cellular damage caused by unstable free radicals.

But an observation made in 1990 by researcher Ronald Hart, who was then studying ageing, nutrition and health at the US National Center for Toxicological Research in Jefferson, Arkansas, highlighted another intriguing possibility. Calorie-restricted rodents fed once daily consumed all their food in a few hours. Perhaps the calorie-restricted rodents lived longer because they repeatedly went for 20 or so hours without eating.

In the immediate aftermath of a meal, cells use glucose from carbohydrates in food as fuel, either straight away or following storage in the liver and muscles as glycogen. Once these sources are depleted — in humans, typically around 12 hours after the last meal — the body enters a fasted state during which fat stored in adipose tissue is converted to ketone bodies for use as an alternative energy source.

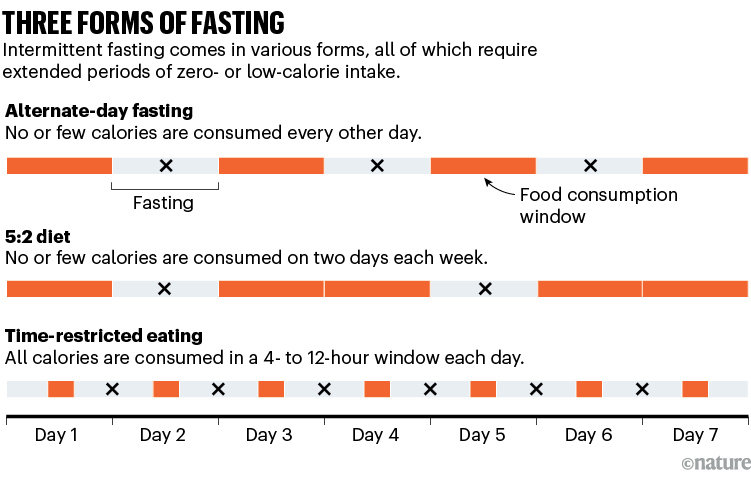

‘Intermittent fasting’ generally refers to various diets that include repeated periods of zero- or very low-calorie intake that are long enough to stimulate the production of ketone bodies. The most common are time-restricted eating (TRE), which involves consuming all food in a 4- to 12-hour window, usually without calorie counting; alternate-day fasting (ADF), whereby people either abstain from food every other day or eat no more than around 500 calories on that day; and the 5:2 diet, which stipulates a 500-calorie limit on 2 days per week (see ‘Three forms of fasting’).

Some researchers say the resulting shift between sources of energy, called metabolic switching, triggers key adaptive stress responses, including increased DNA repair and the breakdown and recycling of defective cellular components. Those responses, the thinking goes, provide health benefits beyond those from reduced calorie consumption alone. Observational studies have suggested that some religious fasters who fast long enough for metabolic switching to occur see such health benefits, although these studies have a lot of limitations.

Getting slim fast

Controlled diet trials are notoriously difficult to conduct. People’s diets and behaviours, together with their genetic inheritance and baseline health, make for a lot of variables. Often, people don’t stick with the study, and getting participants to track calorie intake accurately is a known challenge.

Your diet can change your immune system — here’s how

Still, the weight of the evidence suggests that intermittent fasting can help people to lose weight. In 2022, for example, Courtney Peterson, who researches nutrition at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and her colleagues reported results from a trial involving 90 adults with obesity who also received counselling to help them lose weight. She found that those who followed TRE for an average of 6 days per week over 14 weeks lost an average of 6.3 kilograms, compared with the 4 kg lost by participants who ate over 12 or more hours2. Peterson says that many people find following a rule about when to eat and when not to eat easier than counting calories or eating healthier. “We and others have found that TRE also makes people less hungry, so they tend to naturally eat less and lose weight,” says Peterson.

Also in 2022, nutritionist Krista Varady at the University of Illinois, Chicago, and her colleagues reviewed 22 randomized trials looking at the effects of ADF, the 5:2 diet and TRE on body weight. ADF and the 5:2 diet produced 4–8% weight loss after 8–12 weeks in those with obesity, whereas TRE helped people to lose 3–4% of their body weight over the same period3.

Varady has a long-standing interest in fasting. The cover of one version of her 2013 book The Every Other Day Diet features pizza, a doughnut and a burger to illustrate that those doing ADF don’t need to cut out unhealthy foods. In the book, Varady argues that restricting intake to no more than 500 calories every other day is a more effective way to lose weight than conventional calorie counting and cutting out fatty and sugary foods.

Although most researchers who study intermittent fasting agree that it can help people to lose weight, they’re split on whether there are any benefits beyond those that come from simply eating less. Michelle Harvie, a research dietitian at the University of Manchester, UK, sought to address this question in collaboration with Mattson in a 2010 trial. They found that overweight women who followed a 5:2 diet for 6 months had larger reductions in fasting insulin and insulin resistance than did those on a reduced-calorie diet4. Both groups had the same weekly calorie intake and lost an average of around 6 kg. But the difference in insulin levels was small, and the researchers relied on participants to track consumption by keeping food diaries.

Intermittent fasting often appeals to people who prefer to restrict when, rather than what, they eat.Credit: Roger Bamber/Alamy

In a 2018 study, Peterson and her team carefully monitored the diets of prediabetic, overweight men, matching their diets to energy consumption. The participants ate all their food either within 6 hours before 3 p.m. daily, or over 12 hours, for 5 weeks before switching to the other eating schedule. Although both regimes resulted in equivalent small weight loss over the study period, when men were on the more time-restricted diet, they had improved insulin sensitivity, lower blood pressure and reduced oxidative stress, a form of molecular damage5.

“We showed for the first time that intermittent fasting has health benefits and effects beyond weight loss in humans,” says Peterson. But the study was relatively small: only 12 adults started the trial, only 8 completed it, and all were male and overweight.

Adding to the uncertainty is that other trials have reached seemingly contradictory conclusions. Nisa Maruthur, a physician at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, and her colleagues asked 41 obese adults with pre-diabetes or diabetes to consume diets that matched their energy needs, eating either during a 10-hour daily window or according to their normal schedule. After 12 weeks, there was little difference between the two groups in the average changes to weight, glucose regulation, blood pressure, waist circumference or lipid levels6. “Weight loss seen in prior studies of TRE was probably the result of eating fewer calories,” says Maruthur, whose study was published in 2024. If so, metabolic switching might not come with added health benefits.

Peterson, a co-author of that study, disagrees and suggests that the 10-hour eating window might have been too long to achieve the results seen in trials of shorter TRE windows.

Even though Varady thinks that intermittent fasting can help people to lose weight, she remains unconvinced that it has effects independent of calorie restriction. “Based on current human evidence, I don’t think that there are any benefits of intermittent fasting beyond weight loss,” she says.

Mattson is equally sure of the opposite: “There is considerable evidence of benefits of intermittent fasting that cannot be explained by reduction in calorie intake.”

Mattson and others have looked to animal research in their efforts to understand the physiology of fasting, and to identify mechanisms that could underpin any extra health benefits.