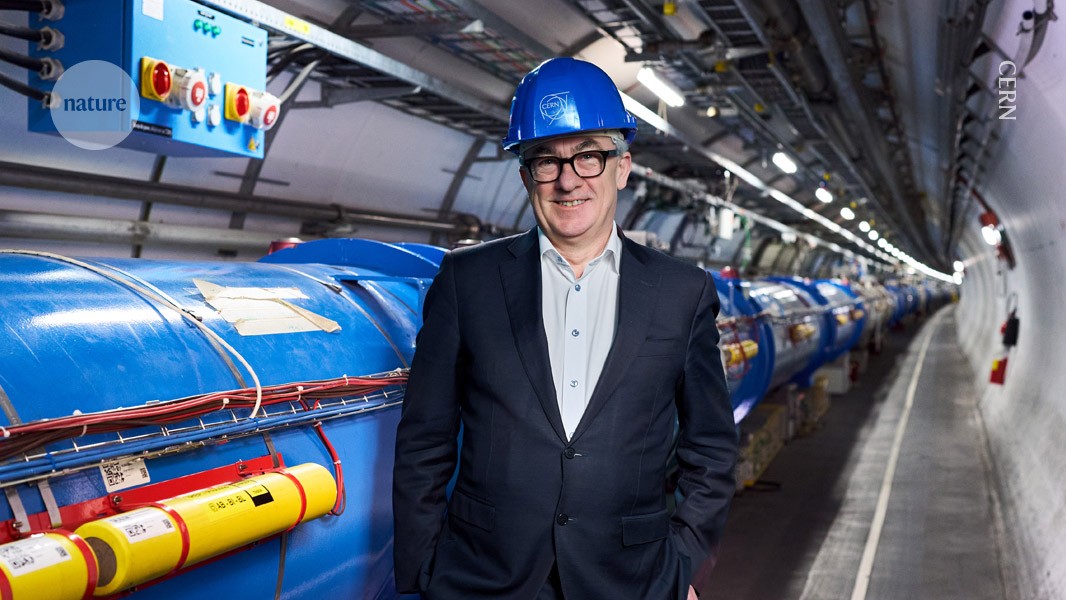

British particle physicist Mark Thomson is director-general of CERN.Credit: CERN

Last month, Europe’s particle-physics laboratory, CERN, announced that it had secured private donations worth an unprecedented €860 million (US$1 billion) towards the cost of building a future collider of epic proportions.

The 91-kilometre Future Circular Collider (FCC), which would span the French–Swiss border and pass beneath Lake Geneva, is forecast to cost around 15 billion Swiss francs (US$19 billion) to make — if it gets built. The machine has the backing of the European Strategy Group, a group appointed by CERN’s council to gather input from its member states and the physics community. But CERN has yet to secure full funding for the project, which would smash together electrons and their antimatter counterparts, positrons, from around 2045.

Nature spoke to CERN’s new director-general, Mark Thomson, a British physicist who assumed the position on 1 January, about what the philanthropic cash injection — from the Breakthrough Prize Foundation, the Eric and Wendy Schmidt Fund for Strategic Innovation and others — means for the FCC, why he thinks the collider should be built and what to expect from his tenure.

This $1-billion commitment is by far CERN’s biggest-ever philanthropic investment. How did it come about?

A lot of that was the result of the hard work of the previous director-general, Fabiola Gianotti. I’ve yet to meet the people investing, but I will. The thing that’s impressed me most is that these are no-strings-attached pledges. They really are there to support humanity’s quest to understand the Universe.

How do you make sure of that?

In the past year or so at CERN, we put in place internal governance around charitable donations. There’s significant due diligence in there, and these agreements are looked at by our council.

Will the extra money help to reduce the contributions required from member states?

Absolutely. About half of the cost of building the FCC fits within the existing CERN budget, so we need to find additional resources of about 7 billion Swiss francs. Some of that could, but doesn’t necessarily have to, come from increases in member-state contributions. Or it could come from philanthropic contributions. In the European Union’s draft Multiannual Financial Framework budget for 2028 to 2034, there’s also a figure for “moonshot” projects that could be up to €3 billion. And, of course, there are our non-member-state partners. We need to really work on putting the pieces together to get to the point where we will be able to, hopefully, convince our member states that we have the money and that this is the right thing to do.

We are just coming out of a long European strategy process for particle physics, where communities have come together in scientifically driven meetings, to discuss the scientific priorities.

Almost every one of our member states and associate member states — their scientific communities — recommended the FCC as the preferred choice for what CERN should do next. That was considering possible alternatives, as well. Scientifically, there’s a big gap between what the FCC can do and what anything else can do. I think only one of the countries was on the fence. That’s really unusual in science.

Some researchers say that CERN should pursue cheaper, more varied experimental strategies instead. What do you think?

You absolutely need a range of experiments. I think we will always need colliders to push that high-energy frontier. But there are other complementary experiments, for example, direct searches for dark matter, that are also important. We have to pursue them all in parallel and, just like an investment portfolio, some things will be at the lower cost end, and some things will be at the higher end.