President James Earl “Jimmy” Carter Jr. died on Sunday, December 29, 2024 at his home in Plains, Georgia, at 100 years old. Carter will be remembered as a consummate humanitarian and Nobel Prize winning statesman who spent his retirement years building houses with Habitat for Humanity and all but eradicating a truly terrible parasite, the guinea worm, from the planet.

He will also be rather unfairly remembered as a weak, ineffectual leader, relegated to a single four-year stint in the White House; a rarity among modern presidents. It’s a reputation pushed by the Greed-is-Good Reaganites who immediately followed Carter’s single-term presidency. But looking back, it’s clear that Carter’s presidency included plenty of far-reaching changes that could have drastically altered the course of America — specifically, our dependency on cars and foreign oil, and our rate of toxic pollution output — if only we had stuck with his plans.

It is far beyond anyone’s ability to sum up such a man, even with a few thousand words to work with, but here’s how Carter biographer Jonathan Alter describes his subject:

With skills ranging from agronomist, land-use planner, nuclear engineer and sonar technologist to poet, painter, Sunday School teacher and master woodworker, Carter was the first president since Thomas Jefferson who could rightly be considered a Renaissance Man.

He was also the first since Jefferson under whom no blood was shed in war. And his record of honesty and decency — once seen as minimum qualifications — have loomed larger with time. At a farewell dinner just before leaving office, his vice-president, Walter F. Mondale, whose job Carter turned from punchline into a position of real responsibility, toasted the Carter Administration: “We told the truth. We obeyed the law. We kept the peace.” Carter later added a fourth major accomplishment: “And we championed human rights.”

Carter served as president from 1977 to 1981, during a time when the U.S. alone consumed one-third of the entire planet’s energy production — much of that going towards fueling the large, criminally inefficient cars of the era. Carter created ground-breaking policies that attempted to reverse this trend, many of which Regan dismantled quicker than a solar panel on the White House roof. Even so, there were some deeply-felt lasting effects of his administration. Carter wrote in his autobiography:

The Congressional Quarterly reported that since 1953 Lyndon Johnson, John Kennedy and I ranked in that order in obtaining approval of legislation proposed to Congress. The Miller Center reported that my record exceeded Kennedy’s.

Indeed, he got his legislative way in Congress 76.6 percent of the time, according to Politifact. He left a deep mark on this country, especially when it comes to the environment and the automotive industry. Carter was the first president to bail out an American automaker, Chrysler, with a $1.5-billion Treasury loan. He was the first to attempt to get oil companies to pay their fair share of taxes during times of record profits (and record gas-pump prices) and the first leader in the world to address global warming, and humanity’s role in it, as a reality.

Carter looked at our wasteful, energy-hungry American culture and struck a solemn — occasionally scolding — chord, imploring us to build toward a brighter future. But such a vision is not sexy, and it’s not fun. It’s certainly not part of what we think of as the go-go 1980s culture. Instead of seriously investing in innovations that would reduce our dependence on carbon-emitting oil from hostile countries, America chose to proceed in an entirely different direction, made clear when the electorate chose Ronald Regan by a landslide in the 1980 presidential election.

“Carter also envisioned electric cars by the mid-1980s, and would have used his power to push automakers in that direction, as he did on CAFE standards,” Carter biographer Jonathan Alter told Jalopnik. Alter believes that a second Carter term would have been much better in a lot of ways. “Starting with more compassion domestically and less saber-rattling abroad, where he would have likely completed the unfinished business of Camp David, namely some comprehensive Mideast peace deal that included an eventual Palestinian state. Carter told me this was his biggest regret about losing.”

Carter won the Nobel Peace Price in 2002, the committee citing his groundbreaking work towards peace throughout his career, both as president and as a private civilian. The Camp David Accords ended 30 years of hostility between Egypt and Israel and remain the longest-lasting peace agreement since World War II.

That’s not to say Carter was without fault. As president, Carter saved Chrysler (and the automaker paid off its debt to the American people seven years early), but the Carter administration also helped establish an emboldened corporate America where workers still regularly bear the burden of highly-paid CEOs’ mistakes. He created a new tax that would directly result in the rise of the SUV, inspiring automakers to revamp their ’70s gas-guzzler shortsightedness for the 21st century. And he led a White House that seemed chaotic and directionless when America yearned for strong leadership.

Let’s take a look at where this influential president went right — and where he went wrong — in his dealings with the American automotive industry.

Taking on Fuel Economy and Big Oil

By 1977, the concept of the modern suburb was only about 25 years old, but had overtaken the American way of life. By the 1970s, the number of cars on American roads had quadrupled in two decades, to 118 million vehicles, and the number of miles traveled by car had doubled. This was the Malaise Era of cars — a time of inefficient, poorly built, uninspired land yachts. The rise of in-car air conditioning shaved even more miles off the U.S. economy average, costing new car owners about two and a half miles per gallon.

Carter addressed this waste in his first address as president:

We have learned that “more” is not necessarily “better,” that even our great Nation has its recognized limits, and that we can neither answer all questions nor solve all problems. We cannot afford to do everything, nor can we afford to lack boldness as we meet the future. So, together, in a spirit of individual sacrifice for the common good, we must simply do our best.

The country was still reeling from the 1973 Gas Crisis, caused after the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries placed an embargo on U.S. oil sales in response to the U.S. re-supplying Israel during the Yom Kippur War. This caused a spike in gas prices and shortages in fuel across the country. OPEC ended its embargo in May of 1974, but fuel prices remained high while oil companies profited immensely.

To prevent another painful energy crisis, Carter’s predecessor, Gerald Ford, had signed into law the first Corporate Average Fuel Economy standard. This policy would eventually be expanded by the energy bill Carter promised in his inaugural address. Passed in 1978 as the National Energy Act, the collection of eight bills created the Department of Energy, pushed renewable energy goals, raised fleet average MPG requirements, reduced oil imports by supporting the U.S. oil industry, and imposed a gas guzzler tax which would increase as CAFE standards tightened.

Carter called the previous administration’s energy crisis the “…moral equivalent of war,” and he planned to come out with both guns blazing. His new Department of Energy would be put to the test just a year after its creation when, in 1979, Carter faced the moral war of his own energy crisis.

The Iranian Revolution and the subsequent hostage crisis sent oil prices soaring from $13 per barrel in mid-1979 to $34 per barrel by mid-1980 — despite the loss in oil supply being estimated at only four to five percent. Long lines at fuel pumps were once again angering Americans. But folksy Carter was famous for facing moral struggles. The president sequestered himself at Camp David for 10 days to consider the energy problems facing America. He met with leaders in business, science and faith, and spent hours alone studying and writing.

After this period of reflection, Carter believed he had identified the problem. In what would later become known as Carter’s Malaise Speech, he cut to the heart of U.S. consumerist culture:

The erosion of our confidence in the future is threatening to destroy the social and the political fabric of America. . . .

In a nation that was proud of hard work, strong families, close-knit communities, and our faith in God, too many of us now tend to worship self-indulgence and consumption. Human identity is no longer defined by what one does, but by what one owns. But we’ve discovered that owning things and consuming things does not satisfy our longing for meaning. We’ve learned that piling up material goods cannot fill the emptiness of lives which have no confidence or purpose.

The symptoms of this crisis of the American spirit are all around us. For the first time in the history of our country a majority of our people believe that the next five years will be worse than the past five years. Two-thirds of our people do not even vote. The productivity of American workers is actually dropping, and the willingness of Americans to save for the future has fallen below that of all other people in the Western world.

While certainly not wrong, saying as much is kind of a bummer. Amazingly, Carter’s incredibly low approval numbers received an 11-point bump after the speech, which was squandered a few days later when Carter fired five cabinet members. His presidency seemed scattered and chaotic heading into the 1980 presidential election.

In order to bring down gas prices, Carter would begin to deregulate domestic fuel markets even as he imposed a large tax on oil company windfalls during the nationwide gas shortages and price hikes. His policies would initially lead to an increase in domestic oil production of nearly 1 million barrels a day between 1980 and 1985, according to the Miller Center. However, the price of oil plummeted in the mid ’80s, and the tax became a significant hindrance to domestic oil production, while not raking in all that much dough for the federal government. It was repealed in 1988; politicians have been twitchy over the idea of taxing massive oil company profits ever since. President Joe Biden recently floated the same idea, which was almost universally panned as being doomed to repeat Carter’s failure.

Carter’s regulation of the auto industry wasn’t perfect, either. During his time in office, Carter expanded a tax on Japanese light-trucks in order to prop up domestic sales. Reagan would build on this policy in 1981, pressing Japanese automakers into “voluntary” export restrictions.

Further, light trucks were exempt from Carter’s strict new MPG standards, and continue to be exempt to this day. These little favors for the automakers would lead directly to the rise of deadly, dangerous and wasteful SUVs and trucks on America’s roads, setting us up for yet another energy crisis in 2022, when gas prices and inflation once again reared their ugly heads.

Carter told the Harvard Business Review he was proactive with automakers about building more fuel-efficient cars even before his own oil crisis. The heads of the Big Three were hesitant to get on board, however:

[…] I called in to my cabinet room the chief executive officers—the chairmen of the board and the presidents of every automobile manufacturer in the nation—along with the autoworkers’ union representatives. I told them we were going to pass some very strict air pollution and energy conservation laws. My hope was that they would take the initiative right then and commit themselves to producing energy-efficient automobiles that would comply with these strict standards. Their unanimous response was that it simply was not possible. I told them that automakers in Sweden and in Japan were doing it, so it was possible. But they insisted that they just couldn’t make a profit on it because their profit came from the larger automobiles. So they refused to modify their designs.

Eventually we passed a law that required them, incrementally and annually, to improve their automobiles’ efficiency and to comply with environmental standards. In the meantime, American manufacturers lost a lot of the domestic market. That was a case of the automobile industry being unwilling to look to the future. They could not see the long-run advantage, even though it might prove to be costly in the close-in years.

That delay would cost Chrysler dearly.

The 1979 Chrysler Bailout

That lack of long-term foresight Carter spoke of in his Malaise speech would send Chrysler spiraling towards something unimaginable in the post-war United States: The bankruptcy of a major American automobile manufacturer. And yet, in 1979 Chrysler faced half a billion dollars in losses.

At a time of rising gas prices and the emergence of stringent federal fuel economy standards, the American automaker was still churning out those poorly-built road yachts. No automaker built them quite as big (or as wasteful) as the Chrysler corporation. At the time, Chrysler was the third-largest automaker in the country, and the 10th-largest industrial manufacturer. By the time Carter took office, America had waded through five years of energy ups and downs, but Chrysler hadn’t changed its vehicles all that much. When the second gas crisis hit, along with the new regulations put in place by Carter’s energy policy, Chrysler fumbled.

The company had recently scooped up celebrity CEO Lee Iaoccoa, fresh off eight years of making money hand over fist for Henry Ford II. Iacoccoa was the fall guy for the Ford Pinto disaster, but had made few friends with his desire to push the company towards more fuel-efficient vehicles. As a sign of the serious situation Chrysler was in, Iacoccoa took a salary of only $1 in his first year as CEO. Iacocca then tried to move Chrysler towards smaller vehicles, but quickly realized his new employer would not be able to weather this financial storm alone.

Iacocca reached out to the feds for help. He persuaded lawmakers that Chrysler was too big to fail. Carter’s Treasury Department was on board, but in order to get enough support in Congress for a loan, the Carter administration would ask the company, and the UAW, to make deep concessions. Treasury Secretary G. William Miller proposed a $1.5 billion loan, then the Carter Administration’s Council on Wage and Price Stability testified before the Senate Banking Committee that such a loan would be consumed in three years flat, thanks to the automaker’s obligations to the UAW.

After a summer of bad press and congressional cajoling, the UAW eventually agreed to $525 million in concessions in late October 1979, along with a three-year wage freeze. Just before Christmas, Chrysler got its $1.5 billion loan in the form of the Chrysler Corporation Loan Guarantee Act.

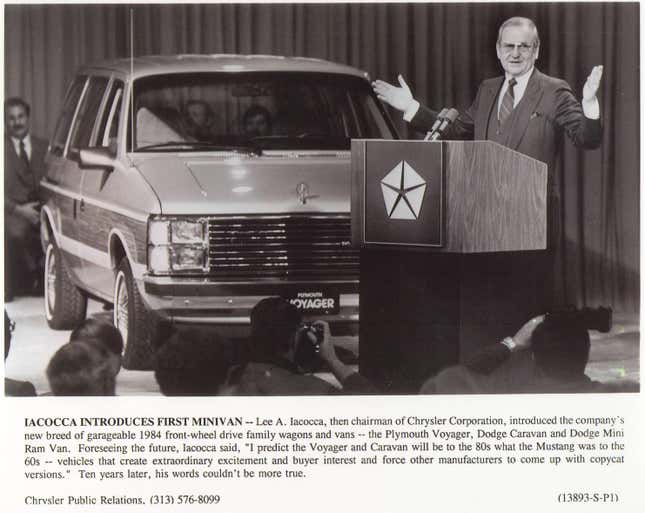

The act did more than just bail out Chrysler. While Chrysler would be subject to more government oversight while paying off the debt — including $2 billion in cost-cutting measures and a three-year plan approved by Congress to get the company back on track — the special act also relaxed the brand-new gas mileage requirements updated by the 1978 National Energy Act. That alone gave Chrysler a much-needed boost, which Iacocca used to springboard the company-saving K-cars and, eventually, the minivan, which came to define the brand in the 1980s and 1990s. This bailout would be used as a blueprint by the Obama administration in 2008 when General Motors and Chrysler found themselves in the same situation Chrysler had faced in 1979.

While Chrysler employees weren’t the ones who made the bad business decisions in the ’70s, they would bear a great burden in the plan to right the company’s course. As they accepted major concessions, union members were painted by the media as selfish and lazy, willing to kill Chrysler to get their golden retirement funds. Even with steep concessions and wage freezes in the middle of historic inflation, Chrysler laid off 57,000 of its 134,000-strong production workforce, the Washington Post reported in a retrospective on the bailout published in 1984. All told, the auto industry as a whole would lay off 239,000 workers in one month in 1980.

Still, Carter biographer Jonathan Alter says saving Chrysler was worth it. “It was a binary decision: Save Chrysler and thousands of jobs or not, and he clearly made the right call for workers, for whom he had much more respect than did Reagan,” Alter told Jalopnik

The damage to unions would last much longer than Chrysler’s debt. The automaker managed to pay off its loan seven years early — mostly to get out from under federal oversight. The U.S. made $300 million on its investment in the company. While Chrysler would thrive in the ’80s and ’90s thanks to Iacocca’s simple, fuel-efficient K-cars and the popular minivan, union membership in America dropped precipitously as Right-to-Work laws swept the nation. And as union memberships stagnate, so do wages.

Carter Was Right

The energy crisis was a key issue to voters who tossed Carter out in favor of Ronald Reagan in a legendary landslide. Having fellow democrat Ted Kennedy challenge the sitting president for his party’s nomination was just one more nail in the coffin of Carter’s re-election campaign. His shaky administration didn’t look any more solid when the president lost consciousness during a 10K run.

Reagan didn’t chide the American public for their gas-guzzling cars. He didn’t ask Americans to spend less, or look deep within themselves and question consumerist culture — Reagan promised wealth, abundance and a revitalization of the American dream (for some, anyway). Once he took office, Reagan stripped the Carter-installed solar panels off the roof of the White House and tossed them in a basement. The dismantling served as a symbol of America rejecting Carter’s old energy policies wholesale. When the solar panels were found in 2010, they still worked.

Carter’s concerns about the U.S. didn’t disappear — we just put them on the back burner for a few decades. Now we’re facing challenges similar to what Carter attempted to address with his time in office: climate change; oil companies profiteering on the back of sky-high fuel prices; the runaway popularity of giant, inefficient vehicles; and detrimental consumerism on a scale familiar to anyone who lived through the 1970s.

So what if Reagan had lost the 1980 election? According to a New York Times op-ed, we might be living in a very different world:

According to a recent report by Amory Lovins of the Rocky Mountain Institute, if the United States had continued to conserve oil at the rate it did in the period from 1976 to 1985, it would no longer have needed Persian Gulf oil after 1985. Had we continued this wise course, we might not have had to fight the Persian Gulf war, and we would have insulated ourselves from price shocks in the international oil market.

Just before Carter left office in 1981, a member of his White House Council on Environmental Quality, Gus Speth, authored a presidential report as part of Global 2000, a process recommending action on global warming. It was the first such policy pronouncement anywhere in the world.

“Speth’s recommendations for tackling climate change in 1981 would be almost identical to the Paris Climate Accords some 34 years later. Such a report would have become part of Carter’s legislative agenda in 1980,” Alter told Jalopnik.

With Jimmy Carter’s death, America didn’t just lose an exemplary humanitarian who doubled the size of the National Parks system and signed 15 major pieces of environmental legislation, including the first toxic waste cleanup. We lost a reminder that our nation once had a head-start on solving some of the greatest problems we face today: environmental pollution, runaway oil consumption, rampant consumerism, a mental health crisis, climate change and Middle East violence. Carter envisioned a different, more responsible America, and he was rejected for it.

Carter’s most enduring legacy will be this: He tried to leave America a little better than he found it. He attempted to warn Americans about the challenges we’d face over the next five decades. Our own legacy shows we were completely unwilling to heed those warnings.