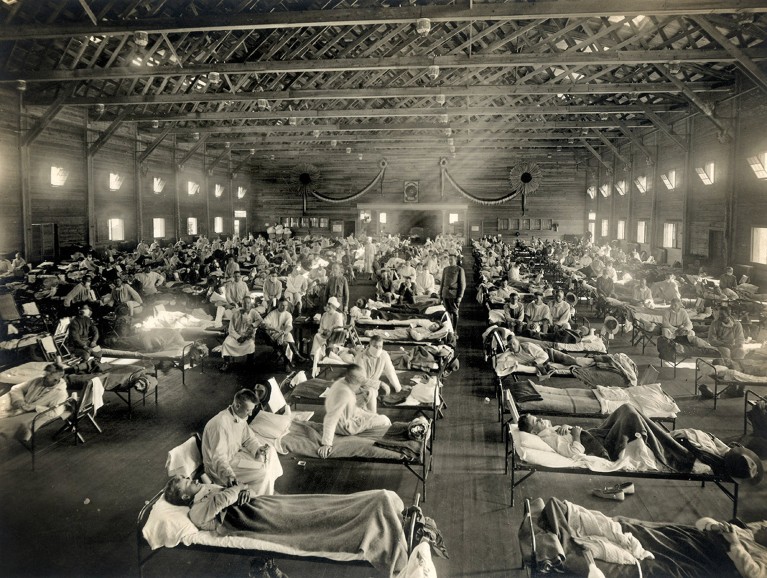

Emergency hospital wards were set up during the 1918 flu pandemic.Credit: NATIONAL MUSEUM OF HEALTH AND MEDICINE/SPL

Of all the pathogens that have plagued humanity, few are as notorious and persistent as influenza. Its Houdini-like ability to regularly slip the shackles of vaccine- or infection-induced immunity, aided by a steady and sustained mutation rate, has created a seasonal viral scourge that wreaks medical and economic havoc all over the world. Here, Nature outlines the history of flu and how it evades attempts to control it.

A short history of flu pandemics

Influenza is never far away. Its seasonality means it see-saws between Northern and Southern hemispheres on an annual basis, causing illness and death among not just humans but also poultry, cattle and birds and mammals in the wild.

Nature Spotlight: Influenza

Every few decades or so, a chance mutation leads to an extraordinary pandemic event that can sweep the planet, claiming millions of lives. The 1918–19 flu pandemic caused 50 million deaths; for the 1957–58 pandemic it was 1 million to 4 million; in 1968–69, the death toll was also 1 million to 4 million; and in 2009–10 it was 105,000–395,000.

Seasonal flu causes 290,000–650,000 deaths, globally each year. In 2015, flu caused losses of US$8 billion in wages and productivity in the United States alone.

The multiple disguises of influenza

Influenza is a single-stranded RNA virus of the family Orthomyxovirus. Although the virus is most commonly referred to as flu, it has many names, subtypes and disguises. Alterations to two key proteins on the surface of the influenza A virus — the spike protein haemagglutinin that allows the virus to attach to host cells, and neuraminidase, which enables the virus to escape from host cells — mean that subtypes are identified according to variations in these proteins.

Of the four types of influenza, only type A causes pandemics. Influenza A (Alphainfluenzavirus) has 198 potential serotypes, consisting of combinations of the 18 known haemagglutinin (H) subtypes and the 11 known neuraminidase (N) subtypes.

Influenza B (Betainfluenzavirus) causes less severe disease than type A and is divided into distinct lineages: B/Yamagata and B/Victoria. Influenza C (Gammainfluenzavirus) causes generally mild respiratory illness in children, but can be more severe in infants. Influenza D (Deltainfluenzavirus) is only known to infect cattle and pigs.

Flu’s known associates

The influenza virus has a broad range of hosts, including cows, deer, horses, dogs, frogs, salamanders, fish and even marine invertebrates. But the favourite host species of the virus is birds, especially water birds, which provide a huge and diverse reservoir of influenza virus subtypes.

Although influenza’s association with people is the most concerning, humans are an uncommon host for the virus. Of the many potential subtypes of influenza A, few have resulted in serious outbreaks in humans. The most notable are: H1N1, responsible for the deadly 1918 pandemic, and H3N2, the culprit behind the 1968 pandemic.

Flu’s distinguishing features

Under an electron microscope, influenza looks deceptively innocent, like a slightly misshapen fuzzy jelly bean. But what really distinguishes it from other viruses is what’s on the inside.

The influenza virus has a remarkably simple genetic structure. The genomes of influenza A and B — the types responsible for most illness in humans — consist of just eight segments of single-stranded RNA. Influenza C and D each have seven segments. The segments of RNA carry the code for the RNA polymerase enzyme that is needed for the virus to replicate, and for the proteins that form the outside of the virus particle.

Influenza is a negative-sense RNA virus. This means that to produce proteins the virus must first generate a positive copy of its genetic code in the form of messenger RNA. Using this disguise, the virus can then hijack the host cell’s replication machinery and use it to churn out copies of its own mRNA and perpetuate its existence.