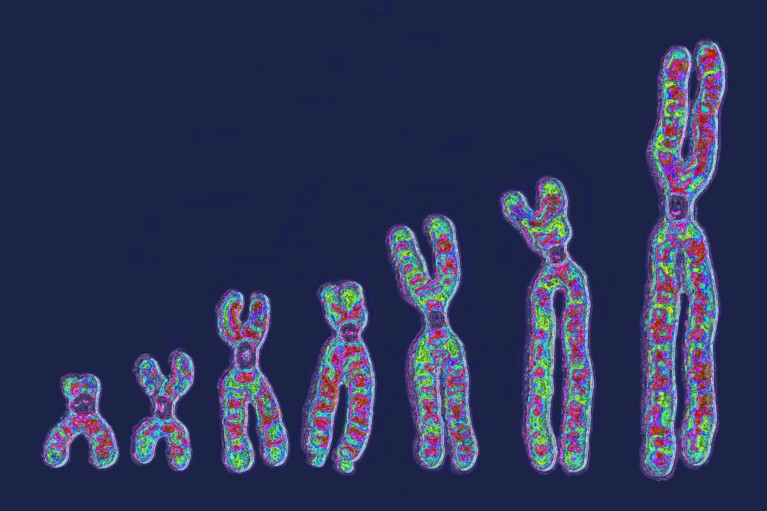

Human chromosomes (artificially coloured) vary widely from cell to cell, according to an investigation of the DNA in more than 100 cells from a single person. Credit: Cavallini James/BSIP/Science Photo Library

In a technological tour-de-force, researchers have sequenced the whole genomes of more than 100 individual cells from one 74-year-old man. The results exposed chaos within: an extra chromosome arm here, a missing chunk of chromosome there, and smaller snippets of DNA altered, deleted or duplicated. In several of the cells, the Y chromosome had been lost entirely.

“There were some cells in there that were very messed up,” says Joe Luquette, who studies bioinformatics at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts, and is an author on the study.

Cancer drugs are closing in on some of the deadliest mutations

The findings, which were posted earlier this month on the preprint server bioRxiv1 and have not yet been peer reviewed, paint a comprehensive portrait of the genetic variation present within a person. That portrait is just the beginning: the study is a pilot project for a US$140-million consortium that aims to catalogue mutations in cells from 19 sites in the body, using cells from 150 donors2.

The resulting catalogue will provide a valuable tool for researchers studying the influence of genetic variation between the cells of a single individual — a phenomenon known as mosaicism — on health and on diseases such as cancer, says Soichi Sano, who studies mosaicism in the cardiovascular system at Japan’s National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center in Suita. “I’m sure that this field will be accelerated very rapidly,” he says.

A lifetime of mutations

People accumulate changes to their DNA over the course of their life, whether from errors that occur during DNA replication and repair, or from exposure to DNA-damaging environmental factors, such as ultraviolet light or tobacco smoke.

As DNA-sequencing technologies have improved, researchers have gained a clearer picture of how common mosaicism is, and how it can affect health. The accumulation of DNA mutations in some cells over time can cause cancer, for example, and loss of the Y chromosome in blood cells is linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease3 and fatal heart attack4.

‘Phenomenal’ tool sequences DNA and tracks proteins — without cracking cells open

But it is difficult to catalogue those differences or to determine when in life they arise. Most genome sequencing is performed by isolating DNA from many cells at once and sequencing it in bulk, making it difficult to detect DNA variants that are present in only one or a few cells. And although methods for analysing the genomes of a single cell are becoming more advanced, these techniques often focus on sequencing RNA molecules, which can be present in many copies per cell, says Diane Shao, a neurologist at Boston Children’s Hospital who has studied mosaicism in the developing brain5. It is a much greater challenge to sequence DNA from individual cells, because there are only two copies of the genome to work with, she says.