Brain imaging has helped researchers understand the role of dopamine in ADHD.Credit: JohnnyGreig/Getty

A couple of years ago, Jan Haavik was at a routine meeting of a research group that connects scientists studying attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) with people who live with the condition. Haavik, a neuroscientist at the University of Bergen in Norway, recalls that one person with ADHD told him: “As everybody knows, we who live with ADHD have very low dopamine levels.”

Haavik was surprised to hear this because the scientific data do not suggest an unequivocal link between low levels of the neurotransmitter dopamine and ADHD. But the idea that low dopamine is a direct cause of ADHD is a common misconception, one that’s amplified on social media and even in popular books about the condition. The reality, Haavik and other researchers say, is that the causes of ADHD are more diverse and nuanced than a simple deficit in one chemical cue in the brain1.

Nature Outlook: ADHD

Links between dopamine levels and ADHD first emerged in the 1960s, when researchers found that certain stimulant drugs relieved symptoms of hyperactivity or inattention. The effectiveness of medications such as methylphenidate (Ritalin) and amphetamine (Adderall), which increase the levels of dopamine and other chemicals in the brain, led to the idea that ADHD was the result of a dopamine deficit, says paediatrics researcher James Swanson at the University of California, Irvine. But the definition was based only on the drugs’ mechanism of action, rather than any direct evidence of dopamine’s role in causing symptoms of ADHD, he says: “The drug corrects the symptoms, so the assumption is that patients have a deficit of neurotransmitters.”

The efficacy of stimulant treatments led researchers to use brain imaging, genetics and experimental models of ADHD to probe dopamine’s role in the condition. Over the years, this evidence coalesced into a framework that is commonly referred to as the ‘dopamine hypothesis’, which proposes that dopamine dysregulation is somehow associated with the condition. But precisely what the dysregulation is, and how it might cause the symptoms that people with ADHD experience, is still uncertain, says psychologist Hayley MacDonald of the University of Bergen in Norway.

The evidence shows that ADHD is a complex condition that cannot be defined simply as a lack of a single neurotransmitter. But researchers have demonstrated how aberrant dopamine signalling can lead to ADHD, and how other neurotransmitters such as serotonin might also be involved.

These advances could eventually lead to a better understanding of ADHD and pave the way to improved treatments. In the United States alone, around 6.5 million children and 15.5 million adults have a diagnosis of ADHD. Stimulant drugs are not equally effective for all those with the condition, however: some people don’t experience lasting benefits, and others struggle with side effects.

Recognizing that ADHD is “more than just a dopamine issue” is the first step towards better approaches to care, says Stephen Faraone, a psychologist and neuroscientist at Upstate Medical University in Syracuse, New York. If researchers can identify the biological mechanisms, he adds, “we may find a better place to intervene”.

Early evidence

Until the 1950s, dopamine was thought to be no more than a precursor to noradrenaline, another neurotransmitter with a similar chemical structure. Then researchers discovered that dopamine had profound effects of its own. Depleting dopamine in rodents made the animals lose control of their limbs, and drugs such as cocaine were found to significantly raise dopamine levels in certain parts of the brain, a surge that can lead to addiction.

Methylphenidate has been prescribed since the 1960s to relieve symptoms of what eventually became known as ADHD. But it wasn’t until about 50 years later that researchers used brain-imaging techniques to confirm that therapeutic doses of the medication sharply increased dopamine levels in the striatum, a region of the brain that is especially responsive to this chemical signal.

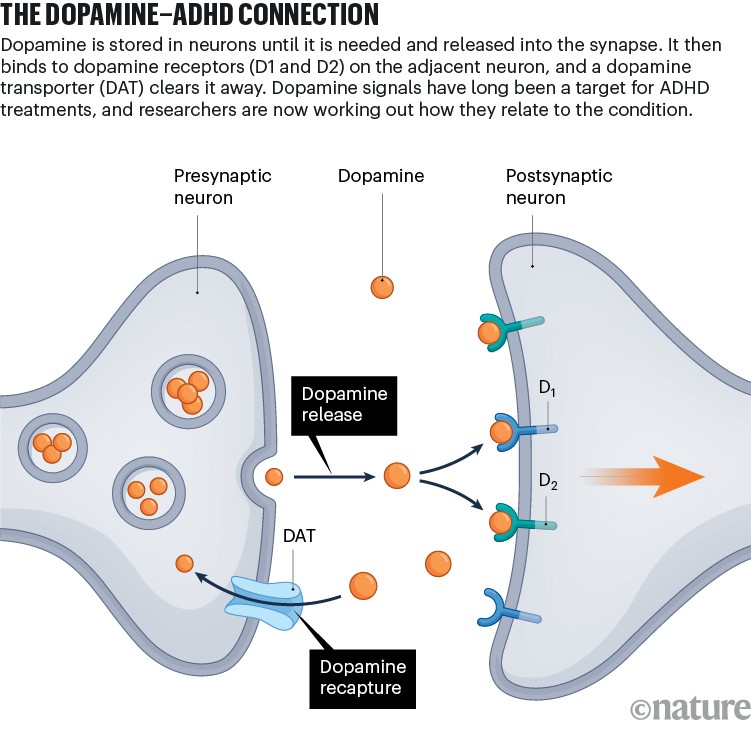

A series of brain-imaging studies in humans also revealed how stimulant drugs such as methylphenidate worked. Typically, neurotransmitters such as dopamine and noradrenaline are stored in neurons until they are needed. When required, neurons release dopamine into the synapse, where it can bind to a dopamine receptor on an adjacent neuron to relay information. Once the message has been delivered, proteins known as dopamine transporters sweep the neurotransmitter away (see ‘The dopamine–ADHD connection’).

Infographic: Alisdair Macdonald

In the early 2000s, researchers showed that stimulant drugs to treat ADHD seemed to work by triggering the release of both dopamine and noradrenaline in the frontal cortex, a brain region closely linked to ADHD and directly connected to the striatum. Another drug, named atomoxetine, which blocks neurons from reabsorbing noradrenaline, had a similar effect.

The drugs prevented dopamine transporters from clearing the molecule away, effectively increasing its levels in the synapse, Faraone explains. Amphetamine also triggered a process of reverse transport, causing transporters to pull dopamine into the synapse rather than sweep it away, further increasing the neurotransmitter’s levels at the synaptic junction.

Knowing that the drugs being used to treat ADHD targeted dopamine-related pathways led researchers to seek out a genetic basis for the condition. Genetic data corroborated the connection between dopamine and ADHD. For example, several studies have identified that variants in genes such as the dopamine-transporter gene DAT1, the dopamine-receptor genes DRD4 and DRD5, and genes encoding serotonin transporters (5HTT) and receptors (HTR1B), could be important for the symptoms of people with ADHD. In a 2014 meta-analysis, Faraone and his colleagues found a correlation between one variant of the dopamine transporter gene SLC6A3 and an increase in the activity of a dopamine transporter in brain-imaging studies of human adults2. These genetic differences could alter the activity of proteins that control neurotransmitter levels in synapses, resulting in differences that might underlie ADHD.

Nuanced effects

Collectively, the data hinted that a possible cause of ADHD was not an overall deficit of dopamine in the brain, but rather a scarcity of the molecule specifically in the synapses. Brain imaging and genetic studies have shown how this synaptic dysregulation might be linked to inattention or hyperactivity.

In a 2007 study, research psychiatrist Nora Volkow of the US National Institute on Drug Abuse and her colleagues compared levels of dopamine transporters in the brains of adults with ADHD who had never undergone treatment with those of people without ADHD. They found that, compared with control participants, people with ADHD had lower levels of dopamine transporters, mainly in two brain regions: the left caudate and the left nucleus accumbens3. This finding indicated that, at least in some instances and brain regions, dopamine levels are not always lower in people with ADHD. They also found that the level of dopamine transporters did not fully account for people’s symptoms: even when transporter levels were the same in the two groups, people with ADHD had scores for inattention five times higher than those of control individuals.

As the team explored further, they found that dopamine’s effects were not limited to pathways related to attention. Instead, the neurotransmitter had a key role in driving motivation to complete tasks. This finding suggests that ADHD is not “just an attention deficit disorder”, Swanson says, but is caused, at least in part, by dopamine’s effects on motivation-related pathways in the brain.

Jan Haavik has shown that the causes of ADHD are more complex than a simple dopamine deficit.Credit: Eivind Senneset

The effects of dopamine in certain brain structures, including the caudate nucleus, are closely linked to the decision to engage in a task or identify it as worthwhile, or to be disengaged and do something else, says Joshua Berke, a neurologist at the University of California, San Francisco. “If things aren’t motivating and exciting to you, then it takes effort and will to sit and keep on doing them.”

As well as motivation, dopamine might also have an important role earlier in brain development. Large-scale, genome-wide analyses indicate that genetic differences could lead to variations in dopamine signals early in life. These different signals might cause subtle changes in brain circuits that could lead to ADHD.

In a 2023 study, Faraone and his colleagues analysed genome-wide data from nearly 39,000 people with ADHD and more than 180,000 controls. The researchers identified 27 regions in the genome that were correlated with a person’s genetic odds of developing ADHD and were important to dopamine signalling in the midbrain region. These 27 genetic loci were linked to 76 genes, many of which are expressed during early brain development4.

Examining the biological pathways that these genes affect revealed “evidence for dopamine and also for these pathways in wiring the brain” early in life, Faraone said. “It’s very likely that one of the results of that differential wiring [caused by the variants] is these problems we see in neurotransmission of dopamine, norepinephrine [noradrenaline] and serotonin.”

Next steps

Understanding precisely how these subtle differences in signalling pathways might lead to ADHD symptoms will require more-extensive studies. “Part of the problem is that our ability to study how dopamine changes and evolves in real time in humans has been very limited,” Berke says. “If you can’t see it changing at the right spatial and temporal scales, it’s going to be hard to have testable ideas about what’s changed in different conditions, including in ADHD.”

But brain-imaging studies are expensive and so are done with small groups of participants. Reproducing data across different research groups has therefore proved to be challenging, Haavik explains. “They can use different tracers and try to target slightly different parts of dopamine signalling,” he says.

Berke adds that dopamine signals are regulated differently in different parts of the brain. In the striatum, for example, dopamine is rapidly sucked back into cells by dopamine transporters, whereas in other regions, dopamine-digesting enzymes break down the molecule instead. Because ADHD drugs seem to act on transporters, they might be less effective in regions in which enzymes are more active. Further studies that rely on a combination of neuroimaging, genetics and measures of brain activity are needed to understand the precise role of dopamine transporters in specific brain regions, Faraone adds.

Clarifying these details could lead to better treatments for the condition. Although stimulant drugs such as methylphenidate have benefited millions, many people experience serious side effects or find that the drugs are less effective than expected.

The portrayal of ADHD as a dopamine deficit is common in popular media, but it can lead to an oversimplified and even harmful view of the condition, MacDonald says. “It can potentially lead to the message that low is bad, more is good, and even more is better.”

Dopamine clearly has a role in the neurological misfiring that underlies ADHD. But researchers have only started to unveil the complex biological mechanisms that connect this essential neurological molecule to the condition — an understanding that could point to more-effective therapies, says Faraone. “We’re at the very beginning of understanding it.”