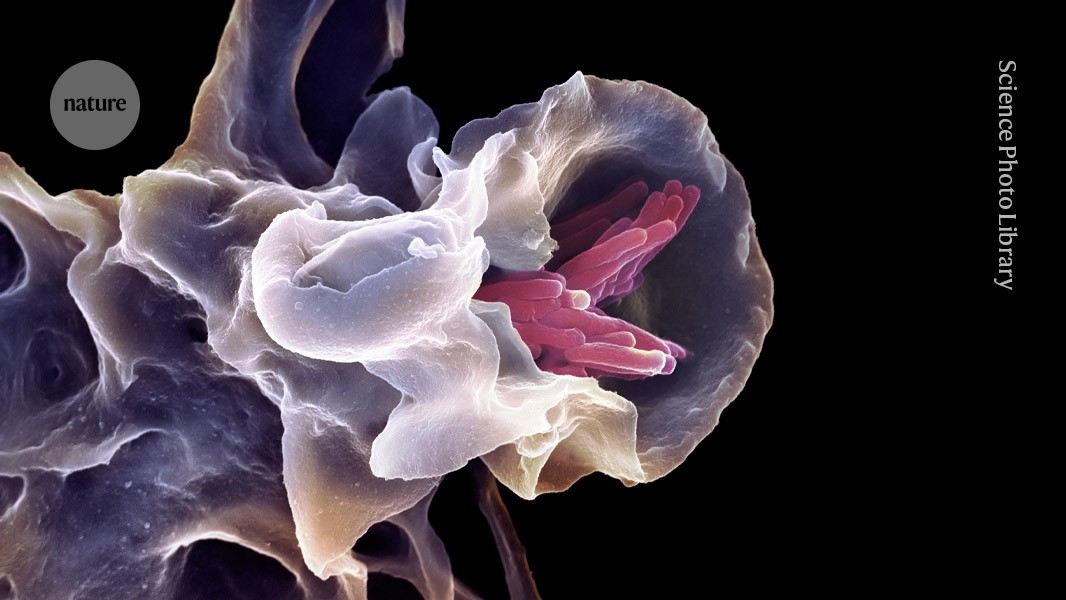

A macrophage — a ‘first responder’ cell in the innate immune system — in the process of engulfing a Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacterium.Credit: Science Photo Library

Imagine if a nasal spray could make you immune not only to the viruses that cause COVID-19 and influenza, but to all respiratory diseases. In a paper1 published in Science today, researchers describe a vaccine that has done just that. When given to mice, the vaccine protected them for at least three months against multiple disease-causing viruses and bacteria — including the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 — and even quelling responses to respiratory allergens.

If the research translates to humans safely and effectively, such a ‘universal vaccine’ could be offered to everyone at the start of each winter — and perhaps provide a first line of defence against future pandemics.

Bali Pulendran, an immunologist at Stanford University in Palo Alto, California, and his group previously studied the Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine2, which provides temporary protection against numerous diseases and works by activating the innate immune system and keeping it active.

This evolutionarily ancient system has a much broader reactivity than does the adaptive immune system — which is the one conventional vaccines utilize by teaching antibody-making B cells and T cells to recognize proteins found on specific pathogens. Activating the innate immune system can also induce the intrinsic capacity of the respiratory system’s epithelial cells to resist infection. These cells are the target of many pathogens.

Double bulwark

In the latest study, Pulendran’s team developed a universal vaccine that targets the innate immune system, with three components. The first two are drugs that stimulate specific receptor proteins that can activate innate immune cells, such as macrophages that reside in the lungs.

The third component stimulates a population of T cells, which are part of the adaptive immune system. Their task is to keep sending signals to the innate immune system to maintain its active state. The vaccine contains an immunogenic protein from chicken eggs, and in experiments in which it was omitted, immunity quickly waned.

Mice that were given four doses of the nasally delivered vaccine developed immunity to SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses, plus to bacteria that cause certain respiratory infections. Another novel benefit was that the activated pathways also suppressed the mechanisms that mediate hypersensitivity to house dust mites, thereby preventing allergic asthma.

Analyses of how the protection works revealed what Pulendran calls a two-bulwark system, in which an initial mucosal barrier limits pathogen entry into the lungs. “Then,” he says, “this mucosal vaccination has set up the lung immune system, so that it is extraordinarily rapid in eliciting the virus-specific immune response to send off those few viruses that slip through the initial bulwark.”

Bridge vaccine

“It’s really a fantastic paper, and it’s exciting. The data look very clear to me,” says Akiko Iwasaki, an immunobiologist at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. “If it works in humans, that would be really quite remarkable.”

Zhou Xing, an immunologist at McMaster University in Hamilton, Canada, says that people who are familiar with the advances in mucosal vaccines over the last decade will not be surprised by the findings. “We call it a ‘bridge vaccine’,” he says — the idea of leveraging the innate immune system to generate non-selective pathogen protection.