Fabrication of artificial muscles

The negative patterns of the artificial muscles were first designed in commercial electronic design automation software (as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1). The patterns were transferred into a photomask by a direct writing laser (DWL2000) machine in a clean room (BRNC). Then we spin-coated the negative photoresist SU8-3025 on a 4-inch silicon wafer. Using standard lithographic fabrication, the patterns were transferred to the photoresist via exposure to ultraviolet light through the mask. After the developing process, the negative patterns of the microbubble arrays, that is, micropillars, were additive on the wafer. The height of the micropillar depends on the spinning speed. Next, to enhance the surface properties, a silane-based hydrophobic treatment was applied to the 4-inch wafer with micropillars for 1 h (see fabrication flow in Supplementary Fig. 12). The PDMS used in this process was prepared with a 10:1 ratio of the base to curing agent. Then the PDMS mixture was poured onto the wafer. To ensure a high-quality coating, the mixture was degassed under a vacuum pressure of less than 1 mbar. After degassing, spin-coating of the PDMS was performed on the wafer. Different spin speeds resulted in varying PDMS membrane thicknesses (Supplementary Fig. 2). After spin-coating, the PDMS was vacuumed again and cured in a sequential heating process: 1 h at 60 °C, followed by 1 h at 80 °C and finally 1 h at 100 °C. Finally, the PDMS soft membrane was cured and then peeled off the wafer. This process yielded a uniform PDMS layer suitable for use in artificial muscle and soft robotic applications. In all our experiments, each cavity consistently trapped only a single bubble as the artificial muscle submerged into the water (Supplementary Fig. 13).

Acoustic set-up

For the microscale characterization of microbubbles, the experimental set-up was built on a thin glass substrate with dimensions of 24 mm × 60 mm × 0.18 mm. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 14, a circular piezoelectric transducer (27 mm × 0.54 mm, resonance frequency 4.6 kHz ± 4%, Murata 7BB-27-4L0) was affixed to the glass substrate using an epoxy resin (2-K-Epoxidkleber, UHU Schnellfest). A square PDMS acoustic chamber (10 mm × 10 mm × 5 mm) was positioned in front of the transducer, which was filled with deionized water and covered with a cover glass (22 mm × 22 mm × 0.18 mm). An artificial muscle was suspended in the centre of the chamber with one end clamped to the side wall and the other end left free. The substrate was then mounted on an inverted microscope (Axiovert 200M, ZEISS).

For the macroscale actuation of artificial muscles by sound, the experimental set-up consisted of a plastic tank measuring 10 cm × 10 cm × 8 cm with a wall thickness of 2 mm. For ex vivo porcine experiments, a larger chamber (30 cm × 15 cm × 15 cm, thickness 2 mm) was used. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 15, the circular piezoelectric transducers were affixed to the inside surfaces and the bottom surface of the tank using the epoxy resin or directly submerged into the liquid. An artificial muscle was suspended inside the chamber with one end clamped, and three cameras were placed around the tank to capture the actuation of acoustic artificial muscles from multiple viewing angles. In addition, a miniaturized endoscopic camera (8 mm diameter and 1080P resolution, FuanTech) was used to capture images inside the porcine specimens. An electronic function generator (AFG-3011C, Tektronix) and an amplifier (0–60 VPP, ×15 amplification, High Wave 3.2, Digitum-Elektronik) were connected to the transducer to generate sound waves with tunable excitation frequencies and voltages. Square waves effectively drive the artificial muscle, achieving maximum deformation and outperforming other tested waveforms, such as sinusoidal and triangular waveforms under equivalent excitation conditions (Supplementary Fig. 16).

Microstreaming characterization

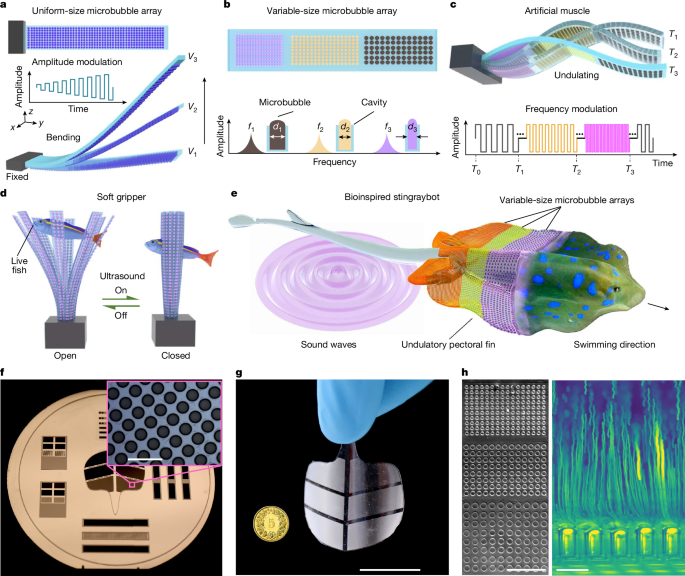

We evaluated the microstreaming jets generated by ultrasound-driven microbubbles embedded in the muscle using 6-μm tracer particles in water and particle image velocimetry analysis. Three uniform-size microbubble arrays, each comprising a 4 × 4 grid of microbubbles with diameters of 40 μm, 60 μm and 80 μm (150 μm in depth), were individually selected and tested in separate miniaturized artificial muscles (500 μm × 500 μm × 200 μm; Extended Data Fig. 3a and Supplementary Video 15). When activated at their respective resonance frequencies 76.3 kHz, 57.4 kHz and 27.6 kHz, we measured the microstreaming velocity 80 μm away from the bubble interface and observed a quadratic relationship between the average velocity and the excitation voltage (Extended Data Fig. 3b). The streaming velocity near the bubble reached 2.5 mm s−1 at 60 VPP. This voltage-dependent microstreaming directly correlates with the reverse thrust generated by the microbubble array, demonstrating that the thrust magnitude can be dynamically tuned by adjusting ultrasound excitation.

We further investigated the selective actuation of a variable-size microbubble array of 40 μm, 60 μm and 80 μm diameter, each 150 μm in depth, integrated within a single miniaturized artificial muscle (500 μm × 500 μm × 200 μm) with corresponding frequencies (76.3 kHz, 57.4 kHz and 27.6 kHz, respectively). The particle image velocimetry analysis revealed that the microstreaming developed by the 80-μm bubbles generated an average velocity of 0.23 mm s−1 at 27.6 kHz, which was markedly stronger compared with the velocities (<0.05 mm s−1) produced by the other two microbubble arrays at the same voltage (15 VPP). Similarly, adjusting the frequency to 57.4 kHz (76.3 kHz) selectively activates the 60 μm (40 μm) bubble array, resulting in more intense streaming at 0.174 mm s−1 (0.075 mm s−1), in contrast to other arrays (Extended Data Fig. 2). Additionally, applying a sweeping frequency (10–90 kHz) over 4 s at 30 VPP enabled wave propagation across the artificial muscle (Supplementary Video 16).

Control experiments on artificial muscle deformation

To determine the key factors influencing muscle deformation, a set of control experiments was performed. We first examined the streaming jets of a uniform-size microbubble-array artificial muscle (1 cm × 0.3 cm × 80 μm) patterned with over 800 microcavities (each 40 μm in diameter and 50 μm in depth). Supplementary Video 17 shows that an artificial muscle without microbubbles exhibited minor deformation, with no noticeable microstreaming observable across the excitation frequency sweeps from 1 kHz to 100 kHz at 60 VPP. By contrast, the actuator exhibited pronounced deformation at an excitation frequency as low as 9.5 kHz (well below resonance), where microbubbles generated microstreaming (approximately 0.8 mm s−1), resulting in substantially greater deformation compared with the case without microbubbles.

Repeatability and characterization of artificial muscle deformation

We assessed the repeatability of the artificial muscle’s deformation under identical excitation conditions, with the transducer close to the microbubble-embedded side, as shown in the left panel of Extended Data Fig. 8a. When stimulated with ultrasound pulses (80.5 kHz, 52.5 VPP and 1-s on/off cycle), the muscle exhibited repeatable bending within 150 cycles, with an error of ±0.8 mm, representing 2.7% of the total beam length (Extended Data Fig. 8b). With more excitation cycles (500 cycles) of the artificial muscle, the deformation exhibited larger error (about 10%). After 10,000 cycles, there were no observable microbubbles in the artificial muscle, and the artificial muscle showed minor deformation. Furthermore, Extended Data Fig. 8c shows a quadratic relationship between the applied voltage and the mean deformation amplitude of artificial muscles, each patterned with uniformly sized microbubbles of 40 μm, 60 μm or 80 μm, when driven at their respective resonance frequencies (80.5 kHz, 62.5 kHz and 30.3 kHz). In addition, the PDMS beam, in the absence of microbubbles, exhibited limited bending (about 7% of the 40-μm microbubble-array artificial muscle’s deformation at 52.5 VPP) caused by the weak radiation force from incident sound waves originating from the transducer.

Control experiments on stingraybot propulsion

In control experiments, a stingraybot without microbubbles exhibited no undulatory motion along its fins under ultrasound excitation and sank without notable lateral displacement (Supplementary Video 18). Notably, under continuous excitation at a single frequency (tested separately at 33.2 kHz, 85.2 kHz and 96.2 kHz at 60 VPP), targeting microbubble arrays with cavity diameters of 66 μm, 16 μm and 12 μm, respectively, the stingraybot exhibited only limited locomotion (<1 body length). By comparison, sweeping-frequency excitation (10–100 kHz over 2 s) elicited sustained undulatory motion, allowing the stingraybot to swim a significantly greater distance (>3.5 body lengths), as shown in Supplementary Fig. 17. These results suggest that the forward motion of the stingraybot is dominated by the propulsion force generated by the sequential undulatory motion, resulting from the reverse thrust generated by the microbubble arrays. Moreover, enhancing the design of the stingraybot with additional microbubble sizes could expand its manoeuvrability. For instance, integrating a navigation tail with microbubble arrays of different sizes on either side enables directional control. When activated at their respective resonance frequencies on one side, these arrays generate an asymmetric torque (Supplementary Fig. 18), enabling steering of the stingraybot via tail rotation. As the stingraybot is stealthy and transparent, we further envision that our stingraybot could be used for environmental data collection or behavioural research on real organisms, for example, detecting water quality within coral reefs and recording swarm interaction by blending into schools of fish.

Robustness evaluation

To evaluate the robustness of our ansatz across fluid media, we quantified artificial muscle deformation in 100% porcine blood, observing amplitudes of approximately 0.4 mm, 1.0 mm, 2.7 mm and 4.4 mm at 15 VPP, 30 VPP, 45 VPP and 60 VPP, respectively, under 96-kHz ultrasound excitation (Extended Data Fig. 9). As complementary evidence, we studied the artificial muscle performance in various aqueous solutions (deionized water, tap water and 25–100% glycerol solutions) as shown in Supplementary Fig. 19. The deformation showed an inverse relationship with glycerol concentration, with the largest deformation of about 11.3 mm in a 25% glycerol solution, followed by about 8.4 mm in 50% glycerol and 3.7 mm in 75% glycerol. The deformation was almost negligible in 100% glycerol. These results clearly demonstrate that the actuator functions effectively in full blood, validating its potential for in vivo applications in fluids with physiological viscosity. We next evaluated artificial muscle actuation in the presence of solid obstructions (Supplementary Fig. 20). A frontal obstruction (partially blocking ultrasound) reduced the deformation by 80–90% (0.5–1-mm tip deformation versus 4.8 mm unobstructed). A lateral placement caused moderate attenuation (about 2.5 mm) and posterior positioning retained a better performance (3.8 mm). Furthermore, experimental results showed significant deformation of the artificial muscle behind excised porcine ribs (Supplementary Fig. 21). Thus, actuators remained functional near obstacles but required strategic positioning to maximize deformation. Our preliminary results also revealed negligible heating effects near the piezoelectric transducer during artificial muscle and stingraybot operation (Supplementary Fig. 22), underscoring the thermally benign nature of our acoustic platform. Although frequency-dependent selectivity was achieved, some cross-excitation between microbubble arrays was observed. This effect was mitigated under sweeping-frequency actuation, and temporal control over the sweep dynamics has a key role in preserving spatial selectivity and ensuring reliable, programmable motion. In vivo biomedical environments present additional challenges such as complex fluid flow, irregular geometry and variable temperature gradients, all of which may distort ultrasound propagation. Although the actuator showed robust and competitive performance under static conditions with other methodologies (Extended Data Fig. 10 and Supplementary Fig. 23), future work will explore flow-resilient designs, including optimized microbubble-array geometries, flexible ultrasound configurations and real-time actuation control strategies to maintain reliable performance in dynamic fluid environments.

Numerical simulations

Finite element numerical simulations were conducted using the commercial COMSOL Multiphysics software (v6.1), including simulations on the acoustic pressure field in the small PDMS chamber, acoustic streaming generated by variable-size microbubbles in the small PDMS chamber, the acoustic pressure field in the big acoustic tank and the deformations of the artificial muscle. All simulations were performed with dimensions and material properties consistent with the experiments. Physics modules of simulations on acoustic pressure include solid mechanics, electrostatics, pressure acoustics fields, creeping flow, and heat transfer in solids and fluids. Simulations on the deformations of artificial muscles were performed using the solid mechanics module with corresponding boundary conditions and force conditions. The microstreaming-generated thrust was assumed to be a point force that is loaded on the bottom of each microcavity. In addition, numerical calculations based on the theoretical model were performed using the commercial Matlab software (version R2021b). See Supplementary Notes for simulation details.

Imaging and analysis

The microscale characterization of microbubbles was recorded with a high-speed camera (Chronos 1.4, Kron Technologies) attached to the inverted microscope. Recording frame rates ranged from 1,069 to 32,668 frames per second. The macroscale motion of ultrasound artificial muscles was recorded with a high-sensitivity camera (Canon 6D and 24–70-mm camera lens, Canon). The recording frame rate was 50 frames per second. Recorded footage was analysed in ImageJ. Statistical analyses were conducted using MATLAB (version R2021b), Originlab (version Origin 2023) and Excel (version 16.54).

Preparation of the zebrafish embryo

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos from pairwise crosses of WIK wild-type fish were raised in E3 medium (5 mM NaCl, 0.17 mM KCl, 0.33 mM CaCl2, 0.33 mM MgSO4) at 28 °C under a 14:10 h light/dark cycle. Experiments up to 5 days post fertilization are not subject to animal welfare regulations. All husbandry and housing procedures were approved by the local authority (Kantonales Veterinäramt, TV4206).

Preparation of the porcine organs

Porcine hearts, stomachs, intestines, ribs and blood were obtained from a licensed abattoir. As the study involved only ex vivo tissues from animals slaughtered for food production, no ethical approval was required.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.