As US science policy continues to shift under the administration of President Donald Trump, the impacts are rippling beyond the nation’s borders. In Canada, researchers are feeling the heat. Canadian academics are some of the Americas’ top research collaborators, and receive funding from US agencies, either directly or through international partnerships. As a result, they have not been spared the funding cuts and job losses that are plaguing their US counterparts.

To Jeff Cardille, a landscape ecologist at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, the trend is clear: all US-funded international projects he’s involved in have been cut since January. These studies focused on deforestation and land-use changes, but Cardille is reluctant to give more details, to avoid putting his colleagues’ jobs in jeopardy.

“It feels strange,” he says. “Two months ago, I would have been thrilled to talk” about the work. “Now, I don’t feel comfortable even mentioning these things existed.”

The loss of these projects disrupts not only his work, but also that of his students who were planning to make them part of their scientific training. “I just recruited a graduate student from Mexico, now I don’t know what I can promise her in terms of research experience,” he says.

Elena Bennett, an ecologist at McGill University (and Cardille’s wife), is also aware of several international projects that have been shut down, including some that she was involved in. She is similarly hesitant to say more.

“Some were just told ‘you’re done, move on’,” says Bennett. “Others are unsure if they’re still going to get funding, if they still have jobs. Everything is on hold until we see how this will shake out.”

The uncertainty, and the seemingly random nature of the cuts and firings, are taking a toll on those affected. “Every time I get on a Zoom call there is another person crying,” says Cardille. “Every meeting feels like a funeral for our careers.”

Ecologist Elena Bennett has witnessed the discontinuation of some projects.Credit: Yannick Peterhans / USC Wrigley Institute

Long-standing links

There is a long history of close partnerships and collaboration in science between Canada and the United States, says Chad Gaffield, chief executive of the U15, a group of some of Canada’s most research-intensive universities, in Ottawa. But in recent years, many countries have begun to focus more on their own domestic capacity to underpin their sovereignty, allowing them to engage internationally without leaving them vulnerable to geopolitical shifts.

“There’s no doubt the world of research is global, but as we learnt in the pandemic, we’re not living in a global village,” he says. “However intertwined we are, borders still make a big difference.”

Researchers in Canada receive funding from a variety of US funding agencies, but the largest share comes from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, Maryland. In the 2023 fiscal year, Canada received more than 90 NIH awards, which amounted to roughly Can$60 million (US$45 million). The total research budget of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) is around Can$1.3 billion.

Researchers at McGill University and its affiliates currently lead 7 projects funded by the NIH and collaborate on another 86 that are led by institutions in the United States, according to a university spokesperson. In the 2023 fiscal year, around 2% of McGill’s total research funding came from US funders, says Dominique Bérubé, McGill’s vice-president of research and innovation, so the direct financial effects of any cuts on the university will be limited. “Cuts to that total won’t impact the university in a major way, but it might impact individuals who are more connected to their US collaborators,” she says.

McGill University leads seven NIH-funded projects and collaborates on dozens more led by U.S. institutions.Credit: Gabriel Mello/Getty

Other institutions, such as the University of British Columbia (UBC) in Vancouver, Canada, are in a similar situation. “Of UBC’s total research funding, only about 1% comes from the US NIH,” says a university spokesperson. The University of Toronto is aware of a few cancelled grants and is continuing to monitor the situation closely, says a spokesperson. But, they add: “At this point, it is too early to fully assess the impact of the current uncertainties for our researchers receiving funding from US government sources, as well as for any research collaborations with colleagues in the United States.”

Vincent Poitout, vice-rector of research at the University of Montreal, says that the university gets between about Can$4 million and $5.5 million a year from the NIH. “It’s not an insignificant amount at all,” he says. Part of Poitout’s own research on diabetes is funded by a portion of a four-year NIH grant, known as a sub-award, held by a colleague at the University of California, Davis. This year’s portion of the award arrived in mid-April, about a month later than usual. The timing was fortuitous: an NIH policy issued on 1 May stipulates that all grants that include foreign sub-awards must be paused until a new formula for such awards is issued in the autumn. “Thankfully, our own grant seems to be safe, but others have been cut,” he says.

However, Poitout says that uncertainty around whether the funding will continue after the autumn is almost worse than knowing it will be cut, especially for the postdoctoral researcher and master’s student who are working on the grant. “It’s starting to create chaos, making people so worried they’re paralysed,” he says. “But I’ll never have my students pay the price, I’ll find a way to continue their training.”

It is not just the potential loss of grant money that is affecting researchers in Canada, says Sarah Laframboise, executive director of the campaign group Evidence for Democracy in Ottawa. She says that the cuts to funding and staff are disrupting a lot of key connections in joint research projects, with Canadian researchers sometimes abruptly losing contact with their US counterparts.

She says that big cuts to staff at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has made fisheries-management collaborations more difficult and could disrupt the data sharing that Canada relies on for weather forecasting and disaster management. “The loss of that data will be very detrimental to not only researchers but everyday Canadians as well,” Laframboise says.

Sarah Laframboise worries about the Trump administration’s restrictions on certain fields of research.

Laframboise is also concerned about the Trump administration’s crackdown on research areas that are considered to be ‘political’, such as anything related to climate, environment, race and gender. Many funders, including the NIH, now have lists of words that could trigger a review of grant applications.

“I worry about the politicization of these words and subject areas, and whether those ideological shifts might come into Canada,” she says.

That concern is not unfounded. Some researchers in Canada who are working on US-funded projects have been sent a questionnaire to determine how their work aligns with the Trump administration’s political agenda, including questions about whether the work contains components on climate justice; diversity, equity and inclusion; or gender ideology. In April, a Canadian cancer-research group involved in an NIH clinical-trials network was forced to remove gender-inclusive language from its trial protocols.

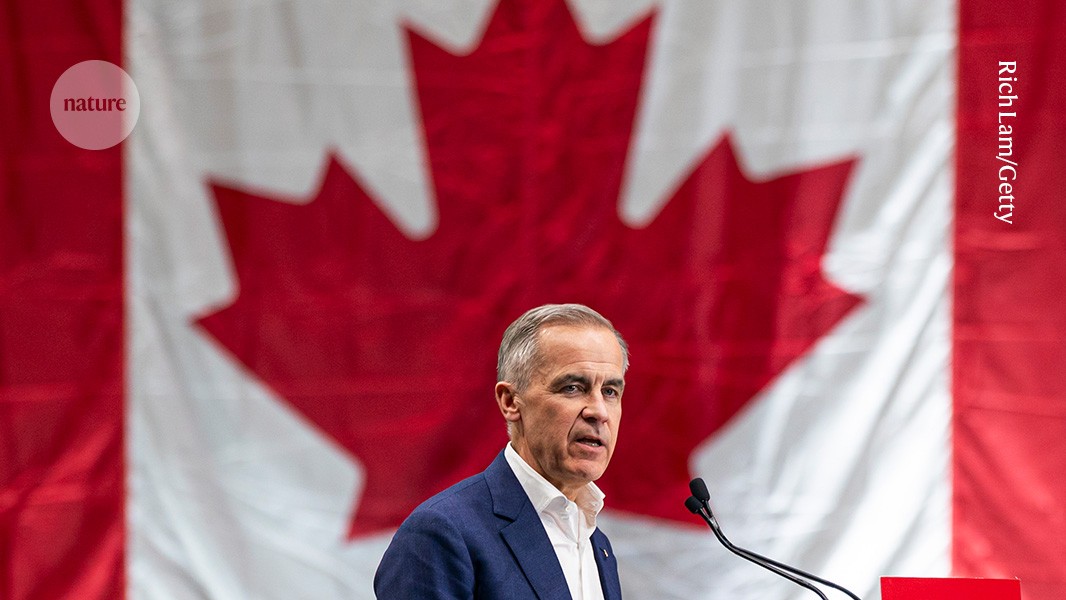

This message has also made its way into the country’s political discourse. During campaigning for the Canadian election in April, the leader of the Canadian Conservative Party, Pierre Poilievre, pledged to end the “imposition of woke ideology in the allocation of federal funds for university research”. On 28 April, the Conservatives lost the election to the Liberal Party led by Mark Carney, who took a harder line against Trump.

Recruitment opportunity

Although the turmoil in the United States has extended to Canada, there is a silver lining — it has provided a potential opportunity to attract talented US researchers looking for international career options. A March poll on the Nature website found that more than three-quarters of respondents were considering leaving the United States for Europe or Canada because of the disruptions caused by Trump’s administration.

“We’ve been very dependent on the US system, however there might be an important opportunity for Canada to re-establish itself in many areas of research,” says Bérubé. Online discussions have started to circulate, centring on how Canada could capitalize on an exodus of talent from the United States. Poitout says that he has already been contacted by some US colleagues about a potential move.

Canada already has programmes in place to attract foreign research talent. The Canada Excellence Research Chairs (CERC) offer either Can$1 million or Can$500,000 per year for 8 years, specifically designed to draw world-class researchers who are interested in relocating their laboratories to a Canadian university. The programme is not offered every year, but the latest competition opened in January 2025, with around 25 positions available.