Even a disease as deadly as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) can start out as just a cough. But as the condition progresses, a person might experience up to 500 respiratory spasms per day. Breathing becomes difficult, as does sleeping. A chronic lack of oxygen increases blood pressure in the lungs. Within 3–5 years of diagnosis, if untreated, a person will experience respiratory failure and die. As the term idiopathic signals, the cause of the disease is not clear, although both genetics and the environment are thought to have a role (see ‘Idiopathic no more?’).

IPF develops more or less in silence, and so it is hard to catch early. “There’s underdiagnosis. People often come to see us pulmonologists when it’s too late,” says Gisli Jenkins, a respiratory physician at Imperial College London.

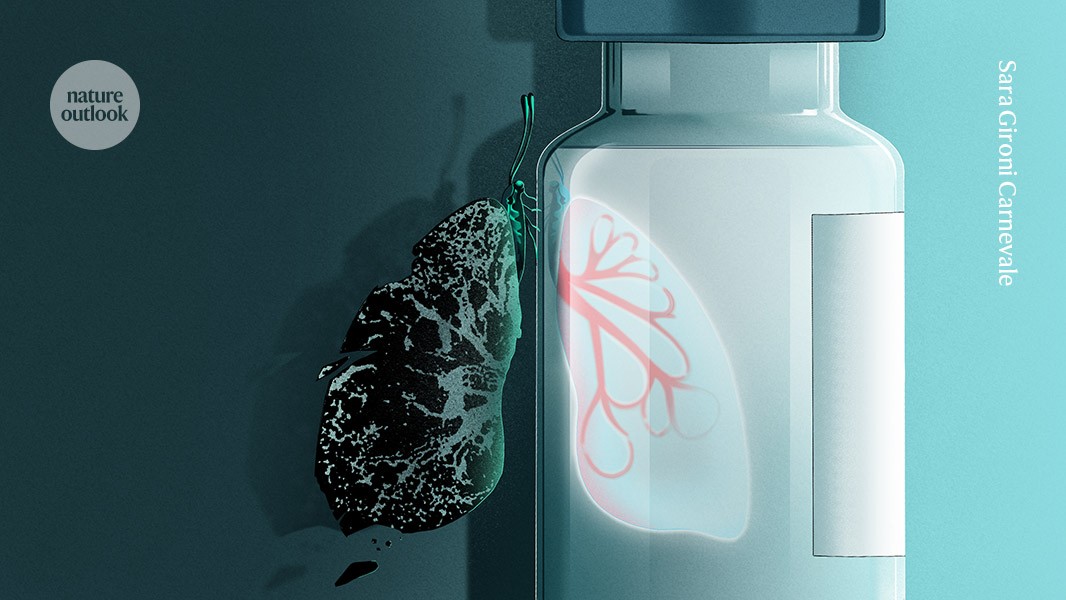

Nature Outlook: Lung health

Attempts to treat the condition — or at least alleviate its symptoms — have largely focused on fibrosis, the formation of scar tissue around the tiny air sacs in the lung known as alveoli. So far, it’s been a rough ride. Treatment with a combination of anti-inflammatory drugs, which was the standard of care for many years, is now not advised because a clinical study1 in 2012 concluded that it not only failed to improve outcomes, but also increased mortality.

In 2014, two treatments were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and have become the current standard of care. The first, nintedanib, targets myofibroblasts — the cells that cause fibrosis in an attempt to repair escalating damage in the lung. Nintedanib inhibits three receptor types that promote these cells’ activity to prevent more damage.

The drug slows down the decrease in forced vital capacity (FVC) — the maximum amount of air a person can forcibly exhale after taking the deepest possible breath. But there is no evidence that it reduces mortality, and it causes burdensome side effects, such as diarrhoea.

The second drug, pirfenidone, reduces the activity of the signalling molecule TGF-β, which typically impels fibroblasts to transform into the myofibroblasts that exacerbate fibrosis. Treatment prolongs progression-free survival by about 25%, and reduces mortality by about half after one year of treatment. But it also has unpleasant side effects, similar to those of nintedanib.

Generic variants of pirfenidone have been available since 2022. The main patents for nintedanib have now expired in Europe and are due to expire in the United States in 2026, paving the way for more affordable generic options. Yet the persistent side effects of these drugs could limit the impact of this opportunity. Many people who take IPF therapies have to change their diets and worry about finding toilets when outside the home.

Less than half of people with IPF in the United States are taking either medication, according to Toby Maher at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. “Pulmonologists have been very reluctant to prescribe drugs that they know patients will struggle to tolerate,” says Maher, who is a pulmonologist and lead investigator on several clinical trials for IPF therapies.

“The drugs don’t improve their quality of life,” says pulmonologist Moisés Selman at the National Institute of Respiratory Diseases in Mexico City, who pioneered the now widely accepted theory that IPF arises from epithelial cell dysfunction2. “Patients often feel their disease is the same — or worse.”

So the search for treatments continues. There are at least half a dozen drugs in development. And one — nerandomilast — was approved by the FDA in October 2025. These treatments generally target earlier stages of lung disease, because established fibrosis is hard to reverse. But none so far reduce mortality, let alone cure the disease.

Elusive targets

Nintedanib and pirfenidone mainly target the later stages of IPF, involving the myofibroblasts that create the scar tissue and the TGF-β pathway that stimulate the cells’ activity. Compounds are being developed to modulate this pathway with more precision. One such compound, GTX-11, reduces the activation of two proteins downstream of the cell receptor that TGF-β binds to. The compound’s developer, GAT Therapeutics in Barcelona, Spain, is now carrying out a phase I trial.

But disappointing results from other trials suggest that it is difficult to target this pathway without creating other problems. After being secreted, TGF-β is usually locked in an inactive state by a partner protein called LAP. One promising approach was to block two transmembrane proteins, called αvβ1 integrin and αvβ6 integrin. These pull on LAP to release TGF-β in response to chemical and physical indicators of injury, such as increasing tissue stiffness, they then often amplify the original indicator. But the approach has run into obstacles.

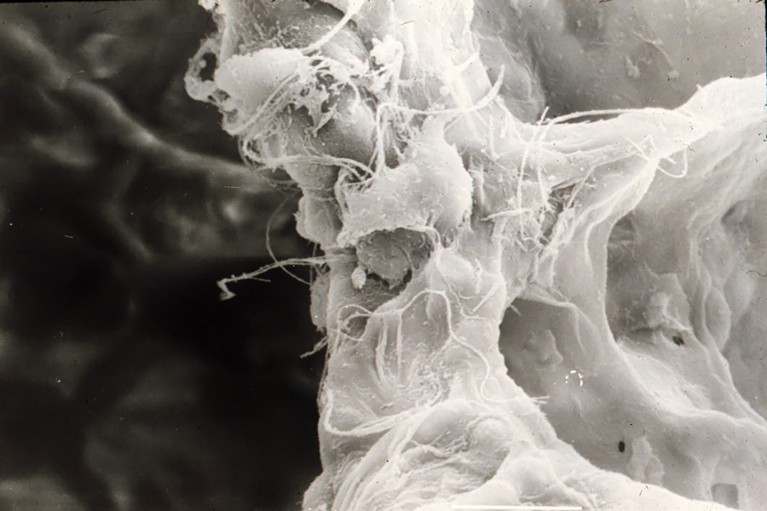

High-resolution scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image showing the three-dimensional ultrastructure of the alveolar septum in the lung. The dense fibrous network represents the extracellular matrix forming the septal framework, while the rounded and irregularly contoured cells attached to the matrix correspond likely to an alveolar macrophage and a fibroblast. Fine fibrillar and filamentous elements are visible across the surface, consistent with the collagen and elastin fibers that provide tensile strength and elasticity to the septal wall. Surrounding voids indicate alveolar air spaces, which facilitate gas exchange.Credit: Moises Selman

In March 2025, a phase II and III trial with a compound called bexotegrast, developed by Pliant Therapeutics in South San Francisco, California, was discontinued owing to adverse events in the treatment groups. These included worsening of IPF symptoms, and a higher risk of death and respiratory-related hospitalization. “Despite all the technology and everything making sense, it didn’t work,” says Jenkins, who was involved in much of the research that inspired the development of this drug. The biology supporting bexotegrast was good, says pulmonologist Paul Wolters at the University of California, San Francisco. “But it’s tough to find the sweet spot between efficacy and toxicity.”

This setback has prompted a reconsideration of whether to target this pathway. “These drugs have a Jekyll and Hyde quality,” says Maher. “They probably are antifibrotic, but also increase susceptibility to acute lung injury.” As a result, he concludes, “integrins are off the table as a target for IPF treatment”.

Jenkins agrees: for targeting integrins, “the ‘just right’ window is very small”, he says.

Some of his colleagues, however, have found other pathways that are involved in TGF-β activation that might be better targets. In IPF-damaged lungs, a dormant developmental program called Wnt signalling is often wrongly switched back on. This directly drives fibrosis, and amplifies the TGF-β signal. A compound called rentosertib promises to target a key regulatory enzyme in the Wnt pathway called TNIK that might help to suppress its aberrant activation, and that of TGF-β3.

The results of a phase 2 trial by Insilico Medicine in Cambridge, Massachusetts, showed that the drug was generally safe and well-tolerated4. At the highest dose, participants experienced a statistically significant increase in their FVC over 12 weeks, compared with a decline in the placebo group. Of the 18 people receiving the highest dose, 4 had to end treatment early owing to adverse side effects such as liver toxicity and diarrhoea.

More-tolerable therapies

Nerandomilast targets the disease process at an even earlier stage. This drug inhibits an enzyme, phosphodiesterase 4B, that suppresses a molecule called cyclic AMP. Under normal circumstances, cAMP slows down the inflammatory processes at the root of TGF-β activation. A phase III trial of nerandomilast by the pharmaceutical company Boehringer Ingelheim finished in September 2024. The trial met its primary endpoints — it slowed the rate of lung-function decline by more than one-third over the course of one year, compared with both a placebo alone or a placebo and nintedanib. “I was very sceptical,” says Wolters. “But I’m happy to eat my hat. I believe the data, which are very consistent.”

Crucially, the trial also found that the number of people who left the trial owing to adverse events was the same for those receiving nerandomilast and those in the placebo group — a major improvement in tolerability compared with other treatments. Diarrhoea is a side effect of nerandomilast, but it was rarely severe enough to make participants of the trial drop out. “From the side effects perspective, it’s a definite winner,” says Jenkins.

Researchers have also attempted to target an enzyme found in damaged lung tissue called autotaxin. This enzyme coordinates the production of a lipid called lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), which binds to a receptor on fibroblasts to recruit them to the injury site. Two large phase III trials investigating the autotaxin inhibitor ziritaxestat were halted in February 2021 after the drug failed to have a significant effect on the decline of FVC. Mortality was also higher for people who took the drug than for those who received a placebo.

One explanation for the failure is that blocking autotaxin or LPA doesn’t fully address the biological issue; the LPA receptor or the pathway might still be activated by a different route. “There’s a lot of opportunity for redundancy in the system,” says Jenkins. Researchers hope that another LPA-targeting drug under investigation, called admilparant, might prevent this from happening.

Admilparant does not limit the production of LPA, but rather blocks its receptor on the fibroblast surface. “The hope is that by inhibiting the key receptor instead, we may be getting the benefits of specificity,” says Maher. A phase II trial that Maher was involved in5 concluded that admilparant significantly slowed decline in FVC over 26 weeks, without causing diarrhoea. The compound’s developer, US pharmaceutical company Bristol Myers Squibb, is now planning a phase III trial.

IPF is thought to be triggered by damage to the epithelial cells that line the alveoli. Another therapeutic approach aims to stop IPF before it takes hold by promoting the repair of those cells. A compound called buloxibutid, developed by Vicore Pharma in Gothenburg, Sweden, activates the angiotensin II type 2 receptor, which suppresses inflammation and promotes cell repair. Participants are now being enrolled in a phase II trial. Any attempt to intervene even closer to the onset of the disease will depend on improved detection of the disease.

Because the drug nerandomilast has less severe gastrointestinal side effects than do older IPF drugs, treatment should be more tolerable for people who don’t yet have serious symptoms. And that, in turn, could make it easier to recruit participants for studies of this earlier stage of disease.

Ultimately, a more holistic approach might be necessary. “The treatment of IPF should probably be a combination of treatments that target different steps of the process,” says Selman. As researchers continue to unravel the origins of the condition, they might move from attempting to slow progression to actively promoting repair. This could turn a fatal disease into a chronic one, or cure it altogether, allowing millions of people to catch a breath.