A dye that turns mouse tissues transparent could have applications in medical research. Credit: dra_schwartz/Getty

A dye that helps to give Doritos their orange hue can also turn mouse tissues transparent, researchers have found. Applying the dye to the skin of live mice allowed scientists to peer through tissues at the structures below, including blood vessels and internal organs. The method, described in Science on 6 September1, could offer a less invasive way to monitor live animals used in medical research.

“It’s a major breakthrough,” says Philipp Keller, a biologist at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Janelia Research Campus in Ashburn, Virginia.

The technique works by changing how body tissues that are normally opaque interact with light. The fluids, fats and proteins that make up tissues such as skin and muscle have different refractive indices (a measurement of how much a material bends light): aqueous components have low refractive indices, whereas lipids and proteins have high ones. Tissues appear opaque because the contrast between these refractive indices causes light to be scattered. The researchers speculated that adding a dye that strongly absorbs light to such tissues could narrow the gap between the components’ refractive indices enough to make them transparent.

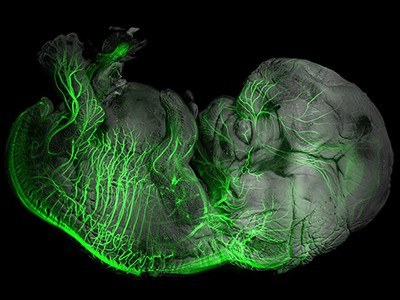

By applying the dye to a mouse’s scalp and using a technique called laser speckle contrast imaging, researchers observed blood vessels within the animal’s brain.Credit: Stanford University/Gail Rupert/NSF

“When a material absorbs a lot of light at one colour, it will bend light more at other colours,” says study co-author Guosong Hong, a materials scientist at Stanford University in California. The team used theoretical physics to predict how certain molecules would alter how mouse tissues interacted with light. Several candidates emerged, but the team focused on tartrazine, or FD&C Yellow 5, a common dye used in many processed foods. “When tartrazine is dissolved in water, it makes water bend light more like fats do,” says Hong. A tissue containing fluids and lipids becomes transparent when the dye is added, because the light refraction of fluids matches that of lipids.

See-through skin

The researchers demonstrated tartrazine’s ability to render tissues transparent on thin slivers of raw chicken breast. They then massaged the dye into various areas of a live mouse’s skin. Applying the dye to the scalp allowed the team to scrutinize tiny zigzags of blood vessels; putting it on the abdomen offered a clear view of the mouse’s intestines contracting with digestion, and revealed other movements tied to breathing. The team also used the solution on the mouse’s leg, and were able to discern muscle fibres beneath the skin.

Transparent tissues bring cells into focus for microscopy

The technique can make tissues transparent only to a depth of around 3 millimetres, so it is currently of limited practical use for thicker tissues and larger animals.

But because tartrazine is a food dye, it is safe to use on living mice, and the method is reversible — when the dye is rinsed off, the skin simply returns to being opaque. This offers a huge advantage over existing methods of making tissue transparent, which are not typically suitable for live animals, and often involve using chemicals to change the refractive index of certain tissue components, or to remove them all together.

The fact that the method produces transparency, is reversible and can be used on live animals “is going to make it an obvious thing that that many people would want to use”, Keller says. Among other applications, he thinks it could be useful in mouse models that aim to understand the nervous system and neurodegenerative diseases.