No one noticed when an old pipe started spewing methane into the sky in the British countryside. The leak, near a railway line and landfill site in Cheltenham, UK, released more than 200 kilograms of methane an hour, yet the invisible gas went undetected. That was until Emily Dowd, a climate scientist at the University of Leeds, UK, spotted the leak in March 2023 while looking through observations from a passing satellite. “It was completely by chance,” she says.

Nature Spotlight: Space research

Dowd had been monitoring the landfill site using data from a methane-detecting satellite 500 kilometres above Earth, built by GHGSat, based in Montreal, Canada. Over the next 11 weeks, she worked with other scientists to identify the exact location of the leak and alert the utility company responsible. “We observed it until it was fixed in June,” she says. Between the time the leak was discovered and when it was fixed, Dowd says, the energy in the methane released was equivalent to the electricity used by 7,500 homes over one year.

Methane is responsible for around 26% of the post-industrial rise in global temperature. Carbon dioxide accounts for a further 70%, and the rest is caused by other greenhouse gases, including nitrous oxide. But methane’s short lifespan of about a decade in the atmosphere, paired with its substantial warming effect, makes it a more immediate target in tackling climate change. “If we reduce our emissions of methane, it buys us time whilst we reduce our CO2 emissions,” says Dowd.

Climate scientist Emily Dowd analyses data from the TROPOMI instrument on the sentinel-5P satellite.Credit: Benjamin Wallis

The Cheltenham incident highlights the growing power of satellites to pinpoint the sources of emissions from space. Although satellites have monitored Earth’s climate for decades, there is an increasing demand to localize these observations and identify accidental leaks, or nefarious releases, from individual sites and facilities. “We want to make these emissions visible so ignorance can no longer be used as an excuse for inaction,” says Riley Duren, chief executive of Carbon Mapper, a non-profit organization based in Pasadena, California.

Methane metrics

Much of the current focus on methane was driven by COP26, the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, UK, at which countries signed a pledge to reduce methane emissions by at least 30%, relative to 2020 levels, by 2030. “Things have evolved greatly post-COP26,” says Jean-Francois Gauthier, GHGSat’s senior vice-president of strategy. “Many have referred to COP26 as the ‘methane moment’.” There are now 155 countries signed up to the pledge, representing half of all global methane emissions.

Between 8% and 12% of methane emissions in the oil and gas industry come from ‘super emitters’, plumes of methane that can be released at rates exceeding 100 kilograms an hour, similar to the leak that Dowd identified in Cheltenham. Super emitters have a variety of sources, including extinguished natural-gas flares that continue to release gas, as well as landfill and livestock. Identifying and halting these plumes is one way to have a rapid-fire impact on methane emissions.

Work is conducted at the site of the Cheltenham gas leak in 2023.Credit: Emily Dowd

Efforts to do so are under way using numerous satellites. GHGSat operates a constellation of 11 satellites to monitor methane plumes, and that number is set to rise to around 40 by 2027, says Gauthier. NASA’s Earth Surface Mineral Dust Source Investigation instrument (EMIT), on board the International Space Station, can track methane plumes, as can the European Space Agency’s TROPOMI instrument on its Sentinel-5P satellite.

Each of these facilities monitors methane plumes in different ways. Some are high-resolution and can target individual facilities; the GHGSat constellation, for example, can monitor emissions as small as 100 kilograms per hour at a resolution of 25 metres. Others, such as TROPOMI, see a much wider field of view.

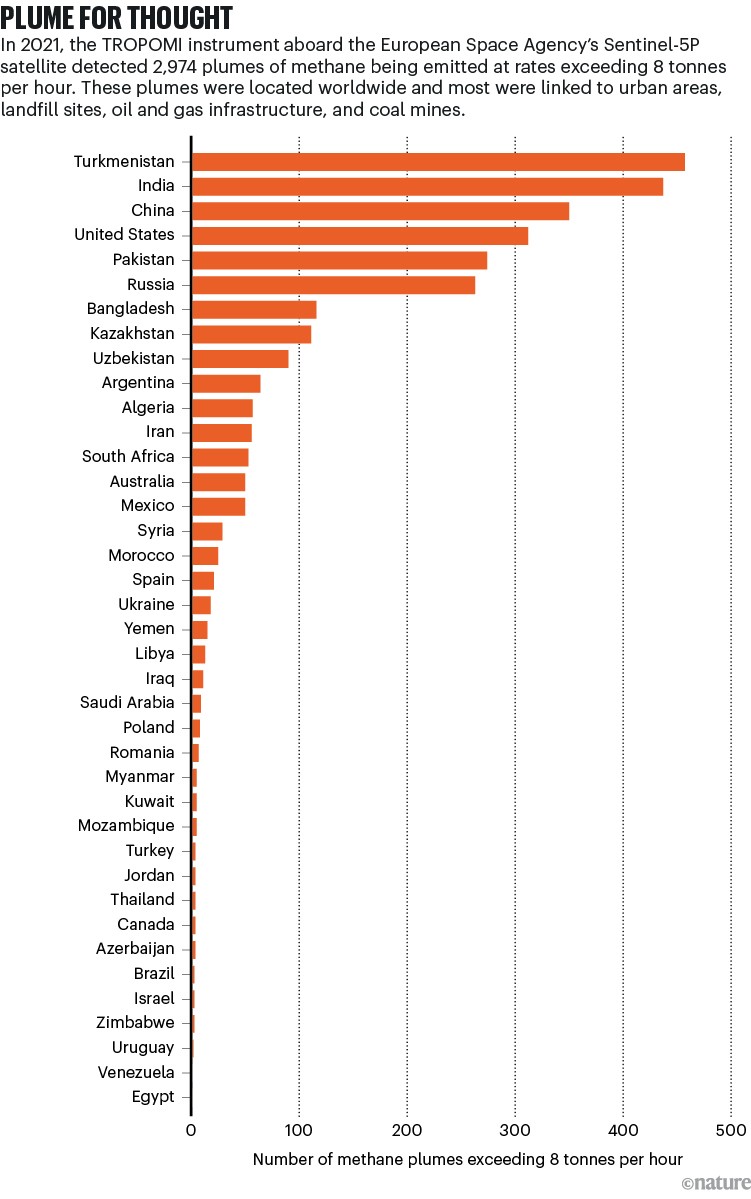

In 2021, researchers used data from TROPOMI to detect 2,974 plumes of methane being emitted at rates in excess of 8 tonnes per hour around the globe1. Of the countries observed, Turkmenistan had the highest number of detectable plumes, with 457 (see ‘Plume for thought’).

Source: Ref. 1

This heightened scrutiny might have influenced Turkmenistan’s surprise announcement at the 2023 COP28 climate talks in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, that it would join the pledge to tackle methane emissions. “That’s something that was unthinkable years ago,” says Gauthier, noting that countries in Central Asia had previously been “quite reluctant to discuss this” for fear of being “named and shamed for their large emissions”.

GHGSat located more than 15,800 plumes across 85 countries in 2023, 33% of which originated in Central Asia. Although no satellite has mapped all of the methane plumes to individual point sources, data from the continuing launches of methane-hunting satellites could bring scientists closer to this goal.

Measured solutions

The influx of methane-hunting satellites is equipping regulators with the tools for action.

The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has finalized its Super Emitter Program, which will allow it to use data from companies such as GHGSat to monitor oil and gas facilities for super-emitter events — methane releases of 100 kg hr−1 or more. Operators of those facilities will be given a short time window to conduct their own investigation into the leak and take corrective action, or risk fines based on the amount of methane released. The programme is expected to be up and running by 2025, when fines will be levied at US$1,200 per 1,000 kg of methane emitted

Ethan Shenkman, an environmental lawyer at Arnold and Porter in Washington DC, says that having high-quality data from satellites will be crucial in this process. “This programme is going to be one of the key mechanisms for bringing satellite data to [focus] on particular facilities,” says Shenkman.

GHGSat senior vice-president Jean-Francois Gauthier says that methane-emissions monitoring is a fast-evolving field.Credit: GHGSat, Inc.

How satellite data are used to crack down on methane emissions will probably differ in each region. “The legal situation in every country is different, so how they will enforce it will be different,” says Beth Greenaway, head of Earth observation and climate at the UK Space Agency, noting that the United States “is a very, very big driver”.

Some satellite operators are using this increased focus on methane as a business opportunity, alongside fighting climate change. GHGSat sells its data to companies so that they can identify leaks or faults in their facilities and address them without any involvement from regulators. “Customers pay us as a monitoring service, and we provide them with regular alerts and reports,” says Gauthier. The company’s ultimate goal is to “keep an eye on every industrial emitter on a daily basis”, which GHGSat hopes to achieve with its planned constellation of 40 satellites.

Even without efforts such as the EPA’s Super Emitter Program, Eric Kort, a climate scientist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, says that the proliferation of satellites to monitor plumes could serve as a deterrent for bad actors before any regulatory action is required, both in the United States and across the globe. “If someone’s going to pass overhead, you might pay a little bit more attention to making sure your flare stays lit, or your valve hatch on your tank stays closed,” he says. “Shining the light is a powerful tool.”