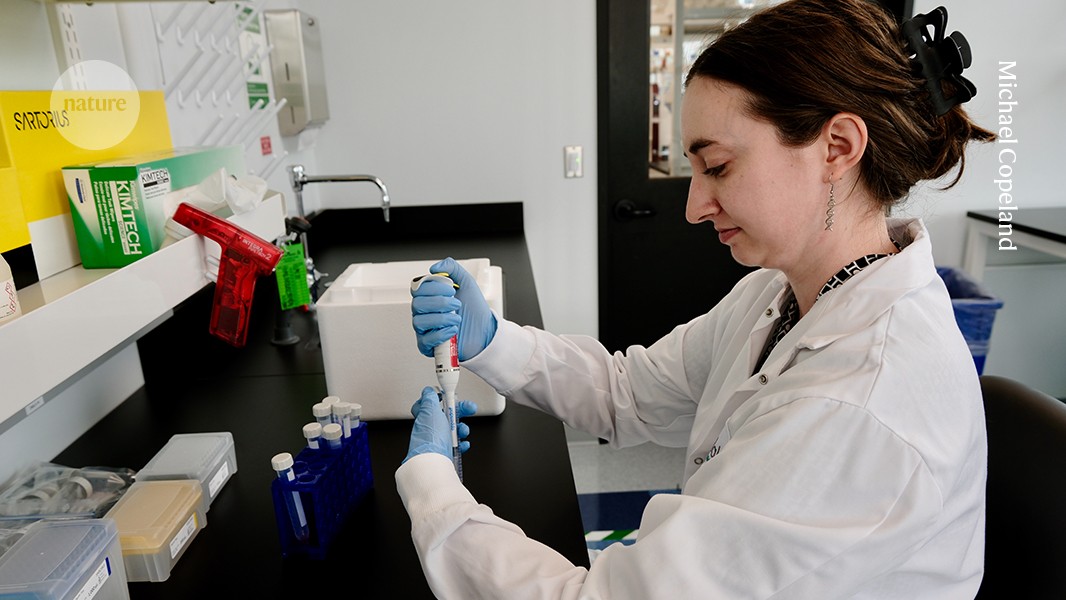

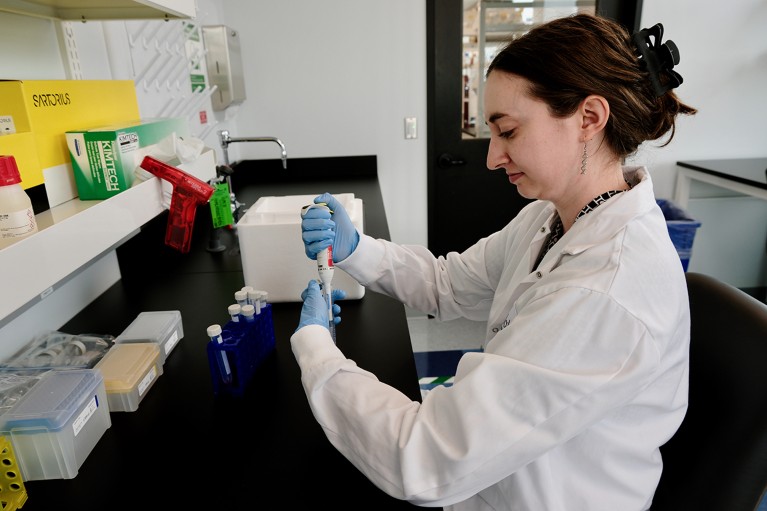

I spend nearly as much time on planning and documenting experiments as I do on running them.Credit: Michael Copeland

Last September, right after finishing my PhD in biomedical sciences, I joined BrainStorm Therapeutics as one of its co-founders and lead scientist.

I stumbled across the biotechnology start-up company, based in San Diego, California, by happenstance: a recruiter for another job I’d applied for unsuccessfully was also recruiting for BrainStorm. A meeting with two of the company’s co-founders clarified for me that we were a good match: I had the niche scientific expertise they were looking for, and the company was exactly aligned with my interests and career goals. I’d known before starting my PhD that I wanted a career in industry, and I’d become increasingly drawn to the fast-paced start-up world.

And Brainstorm’s mission, to overcome the more-than-90% failure rate of clinical trials involving neurological diseases, by using brain organoids for drug discovery, appealed to me. During my PhD at the University of California, San Diego, one of my projects focused on modelling human diseases using brain organoids.

A brain organoid is essentially a tiny 3D sphere of brain cells that we grow from stem cells derived from a patient. The organoids act like mini brains, with multiple cell types and spontaneous electrical activity. In contrast to conventional disease models involving mice, which have largely failed to predict efficacy of treatments in humans, organoids present an all-in-human system to evaluate therapeutics using clinically relevant screening endpoints. BrainStorm uses brain organoids in combination with artificial intelligence (AI) to discover therapeutics for diseases including Parkinson’s and rare genetic epilepsies.

For me, landing this role is a great example of how luck often plays a major part in our career trajectories; sometimes you just have to be in the right place at the right time. It’s certainly not easy — by the time I spoke to the recruiter, I’d already spent several months unsuccessfully applying for jobs while wrapping up graduate school — but persistence is key.

In my first few months, I’ve seen first-hand how biotech is a wildly different beast from academia. It soon became clear that organizational skills, which I’ve written about for Nature’s Careers section, are even more crucial in business than they were during my PhD. These skills, incidentally, served me well: I graduated in five years on the dot, well below the average for my laboratory, despite facing delays as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, and twice going on strike as a member of the University of California academic workers’ union.

Time management for entrepreneurs

In a previous article for Nature, I mentioned that one of the most challenging aspects of graduate school for me was that it’s easy to waste days on unimportant or unfocused work. This is doubly true as an entrepreneur. You’re your own boss, so there’s no one else to hold you accountable and ensure that you spend your time and energy wisely.

Just like during graduate school, I manage my goals at an annual, a quarterly and a weekly level. I always start with the big picture: where do the other co-founders and I want our company to be, a year from now, and how should we be spending our time to accomplish this? These goals will inevitably shift, too, so it’s important to revisit the conversation regularly. I use a Notion page to track our high-level goals over time.

I’ve learnt that a common challenge for biotech start-ups is to work out how much effort to devote to fundraising, as opposed to research. There’s no single answer that works for every company, but it’s important to regularly audit whether you’re balancing these tasks appropriately for your goals.

I’ve continued to plan how I’ll spend every hour in my workdays, using the task-management tool Todoist and Google Calendar. I build this plan after our Monday-morning meetings, in which the team discusses goals for the week and divides up action items. Once a month, I look back at how I’ve spent my time and evaluate whether I need to make any adjustments.

For a start-up on a lean budget, time is your most valuable asset; guard it closely. Don’t be afraid to decline commitments that don’t align with your long-term vision.

Time management for scientists

As I did in graduate school, I take 5 minutes first thing every morning to check my RSS-feed aggregator and bookmark any papers that I want to read later. I block out an hour or two on Friday mornings to read through these and take notes. I also like to set aside time for continued learning; there are a ton of free or low-cost online courses available from sites like Coursera, Udemy and edX. During my lunch break, I’ll often watch course videos on topics ranging from AI and programming to business and finance.

I have a lot more meetings these days (internal discussions, investment pitches, networking events and so on) than I did in graduate school, so my calendar varies a lot, day-to-day. I try to batch meetings together in the first or the second half of the day, so that I can spend the other half focusing on research. I spend a large portion of my time growing organoids and running experiments, as well as writing code for AI disease-modelling work.

Academia is the Wild West when it comes to lab notebooks, in that nothing is standardized, but record-keeping becomes a lot more serious in industry (I think this is true in any company, even more so for one engaged in biomedical research). Maintaining a detailed electronic lab notebook is crucial for documenting inventions, ensuring regulatory compliance and building an organized data repository (this can be virtual) for investors. I spend nearly as much time planning and documenting my experiments as I do actually running them.