Studying age-related diseases gives researchers a better understanding of the risk factors that affect people in later life. By focusing on heart disease, Alzheimer’s and obesity — conditions that have major quality-of-life implications for ageing populations — these three early career researchers are bringing fresh perspectives to a fast-moving field.

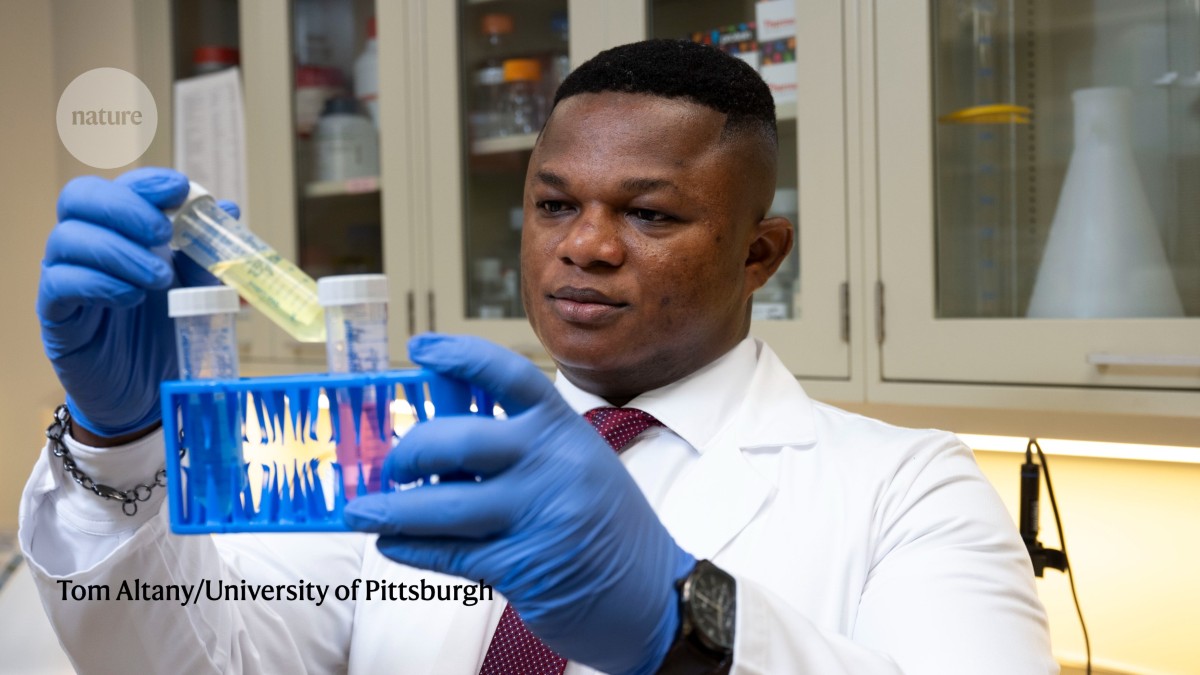

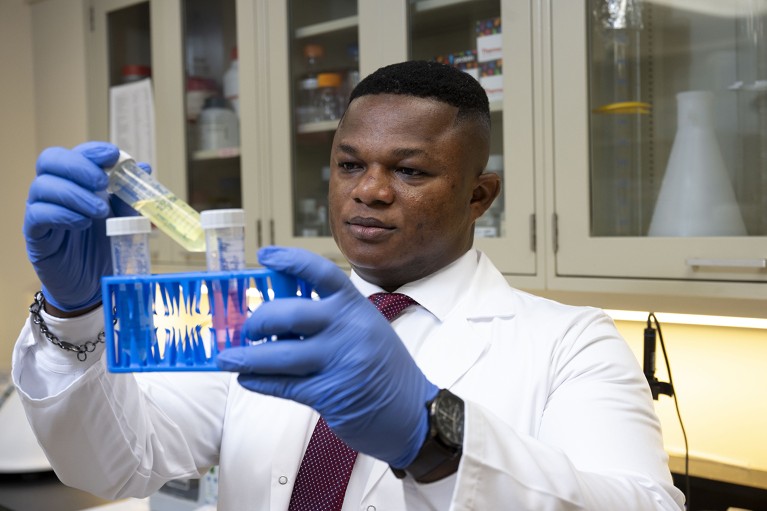

THOMAS KARIKARI: Targeting tau

Thomas Karikari wants to develop more accessible blood tests for Alzheimer’s disease.Credit: Tom Altany/University of Pittsburgh

Two key hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease are tangles of tau proteins that form inside neurons and amyloid plaques that build up between the neurons. Brain scans and spinal taps are useful for detecting these abnormalities, but Thomas Karikari wants to give patients a less invasive option: a simple blood test.

“We need to find the best ways of understanding and identifying individuals who may be at risk,” says Karikari, a neuroscientist at the University of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania. A blood test, he says, “can provide a snapshot of what’s happening in the brain, even up to 20 years before symptoms manifest”.

Early in Karikari’s career, the general consensus around blood-based tests was one of incredulity, he says. “Everyone just went: ‘No, no, no, we don’t talk about it because they’re too difficult to do’.” So, as a postdoctoral student at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, he set himself the challenge of designing a blood test that can detect a form of tau called p-tau181, which exists in high levels in the brains of people who have Alzheimer’s and accumulates as the disease progresses.

Nature Index 2025 Ageing

After screening dozens of antibodies, Karikari and his collaborators had a lightbulb moment: the part of the tau protein that is commonly detected in blood is the left end section — not the middle part that spinal-fluid tests usually target. This insight helped them to design antibodies that could bind to the left portion of the tau protein in a blood sample. The discovery was like “cracking the code”, says Karikari, and the team went on to develop a blood test1 that detects p-tau181 with an accuracy of more than 82%.

Since then, Karikari has developed numerous other blood tests for Alzheimer’s disease, including two that can detect p-tau217, another blood biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease2.

Alzheimer’s blood tests have limitations, which has curbed their widespread use. For one thing, labs use different methods to measure the same protein, which means the results aren’t always consistent. And the fact that tau doesn’t just appear in the brain, but is also common in the liver, kidney, heart and other organs of a healthy person means “we might run into some false positivity” when it’s detected in the blood, says Karikari. One of the blood tests that his team has developed specifically targets brain-derived tau3.

A key driver of Karikari’s work is making tests accessible enough to be used in places such as his home village of Manfo in Ghana. Blood tests are often difficult to use in remote and low-resource settings because the samples need refrigeration, and the analysis equipment requires trained staff to operate.

Karikari’s lab has developed a pared-back method for detecting amyloid plaques that requires smaller blood samples than other tests4. His lab has also developed “remote-friendly tools”, such as a collection tube that can store blood at room temperature for up to 96 hours5. “I will feel most accomplished when all that we are doing gets to reach my village,” says Karikari. — Sandy Ong

LAURA GRAY: Fighting fat

Laura Gray believes body mass index is often not the best way to determine obesity.Credit: FilmFolk/Vivensa Foundation

Laura Gray wants researchers and clinicians to stop using body mass index (BMI) exclusively to measure obesity rates, especially in older people. Beyond 60 years old, the average BMI — calculated as weight divided by height squared — across the population decreases, she says, which doesn’t accurately reflect what’s really going on with obesity rates.

“It looks like they’re losing weight, but actually, it’s because they’ve often lost muscle instead of fat,” says Gray, an econometrician at the University of Sheffield, UK, who incorporates economics and statistics to map how trends in ageing and obesity interact across populations.

BMI does not distinguish between muscle mass, fat mass and other factors such as bone density and water retention, which can lead to confusing results. For example, at their peak, American footballer Tom Brady would have been classified as overweight, and Jamaican sprinter Usain Bolt as nearly overweight, due to their high muscle mass skewing their BMI.

BMI is also an unreliable measure to use with children, says Gray, because of the way it fluctuates during growth spurts.

When Gray and her colleagues tracked the BMIs and health conditions of people over 50 in England between 1998 and 2015, they found that declining BMIs were linked to higher rates of diabetes, asthma, arthritis and heart problems6. “We associate a decrease in BMI with positive health outcomes, but in older people, it might be the opposite,” she says.

As one of the most widely used metrics in public health, BMI would be difficult to replace entirely, says Gray. “It’s so ingrained in everything.” Instead, she recommends looking at BMI trends over time — rather than at single snapshots — to assess a person’s health risks.

Gray likes to use other metrics alongside the BMI, such as waist-to-height ratio, which directly reflects harmful belly fat at any age. When she and UK-based econometrician, Magdalena Breton, used both BMI and waist-to-height ratio to analyse the health data of more than 120,000 people in England, they found that waist-to-height ratio was better at showing how obesity risk increases with age, especially in older adults. The study7 is under peer review.

One trend that Gray is watching closely is the use of popular weight-loss drugs such as Ozempic. She suspects they will start to make a dent in obesity rates at a global population level, but worries that inequities will grow between people who can and can’t afford them. “There are just so many [obesity drugs] coming out, and they are so effective,” she says. “It’s come from a situation where there was just no treatment. It’s a massive switch.”

Obesity is a fascinating condition because of how tied it is to social changes over time, says Gray. “It’s really interesting how it affects so many people now, and 50 or 60 years ago, it wasn’t so much of a problem.” — Felicity Nelson