Credit: Getty/Shutterstock

Do you ever feel that agreeing to review an academic paper guarantees a wasted workday? You’re not alone. Many researchers spend hours marking up a manuscript, only to realize that they need even more time to let everything sink in before they can write coherent feedback. Not surprisingly, they’ve started turning down review invitations — it’s the only way they can safeguard their time and energy.

But science is a community endeavour, and we all know that many editors struggle to find qualified reviewers who can deliver quality feedback to tight deadlines. We also know that when the most knowledgeable people keep declining editors’ requests, science suffers.

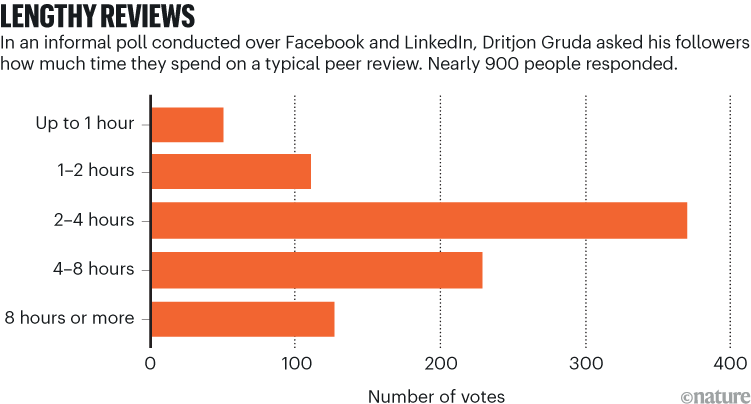

To find out more, I conducted an informal poll over social media. In posts on Facebook and LinkedIn in January, I asked how much time academic colleagues spend reviewing papers. Close to 900 academics responded, with more than 40% saying they typically spend two to four hours on a single review, over 25% indicating that they spend more than four hours on the task, and a remarkable 14% admitting that they put in significantly more than four hours — sometimes a full eight-hour day or even more (see ‘Lengthy reviews’). Some respondents were stunned by those numbers, especially considering how fragmented or shallow reviewer feedback can seem to authors trying to make sense of it.

What if there were a more efficient way to review a paper — without jeopardizing the quality and integrity of the process? Over the years, I’ve fine-tuned a method that has helped me to drastically cut the amount of time I spend on each review, while still providing thorough, constructive critiques. Here’s how it works.

Scan, dictate, refine

I break the review process down into three simple steps:

Scan. Quickly browse the abstract, introduction, methods and results, focusing on the big picture. If the analysis looks solid, read the rest of the paper. If you detect glaring flaws, however, you’ll know it’s probably one to reject — no need to line-edit the entire manuscript.

Dictate. Use dictation in the text-editing tool of your choice (for example, Voice Access in Windows or Voice Control on the Mac) to capture real-time thoughts as you read. This way, you avoid having to scribble notes or needing to recall and type up your feedback later — a major time-saver.

Refine. Feed your dictated notes into an offline large language model (LLM) to clarify and organize your feedback. A simple prompt such as “Write a critical reviewer letter based on the following notes. Maintain a professional tone throughout” will do. Don’t know how to code? No problem. Tools such as GPT4ALL (see ‘How to set up and run a local LLM’) allow you to load and run LLMs locally and offline, so there’s no need to upload sensitive manuscripts to the cloud. Confidentiality is non-negotiable when it comes to unpublished research, and uploading content externally can invite ethical or even legal trouble.

But let’s be clear: LLMs aren’t there to crank out a full review on your behalf. Although survey data published on the arXiv preprint server in January suggest that automated scholarly paper review (ASPR) can help to speed up evaluations and sharpen structure, ASPR tools still struggle with domain-specific expertise, bias and data-security issues1. Instead, use the LLM to spot redundancy, refine phrasing and organize suggestions (for prompts, see my previous column). You — the reviewer — must make the final judgement on the paper’s methodology, findings and overall contribution to the field.

By the end of this process, you should have a set of structured, section-by-section comments that can be quickly refined into a coherent reviewer report. But be sure to check the publisher’s policy on generative artificial intelligence (AI) before you get started. Some are fine with reviewers using generative AI tools to tidy up written feedback. But uploading a manuscript or review text to the cloud is usually a hard ‘no’ — confidentiality is on the line. Running an LLM offline locally keeps you within policy restrictions and safeguards the authors’ anonymity. Plus, it prevents their work from being scooped up for training future LLMs.

Outcomes and lessons

This workflow has helped me to reclaim countless hours in my schedule: I used to spend half a day on one manuscript; now 30–40 minutes suffice if the paper’s methods are sound. If there are serious flaws, it’s even faster — there’s no need to polish an unpublishable paper.

The comments I do make are generally more thorough than before: dictating comments in real time forces me to ‘talk through’ the paper rather than scribble notes, and to articulate critiques on the spot, often exposing logical gaps I would otherwise have missed. It also deepens my engagement with the paper, resulting in clearer, more focused feedback.