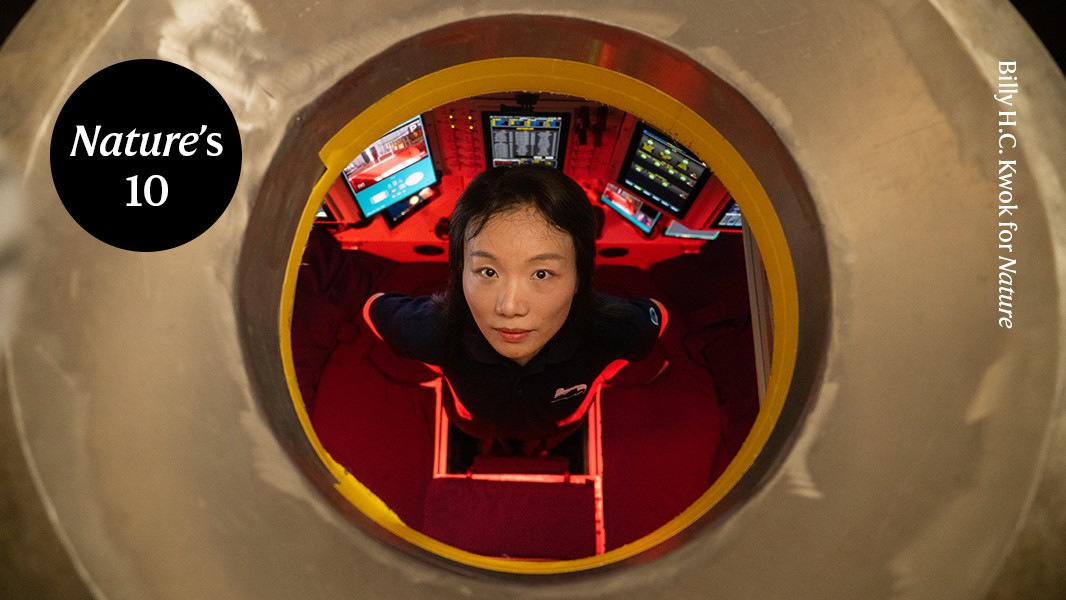

Looking out of the Fendouzhe submersible, more than nine kilometres below the ocean surface, Mengran Du knew she was seeing something totally new to science. The vessel’s lights illuminated a thriving ecosystem in which ghostly bristleworms swim among fields of blood-red tubeworms.

Du and her colleagues were exploring the hadal zone — the lowermost layer of the ocean, found beyond depths of six kilometres. Here, at the bottom of the Kuril–Kamchatka Trench northeast of Japan, Du and her team discovered the deepest-known ecosystem with animals on the planet during dives in 2024, which they described this year (X. Peng et al. Nature 645, 679–685; 2025). “As a diving scientist, I always have the curiosity to know the unknowns about hadal trenches,” says Du, a geoscientist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Deep-sea Science and Engineering in Sanya, China. “The best way to know the unknown is to go there and feel it with your heart and experience, and look at the bottom with your bare eyes.”

The ecosystem discovered by the Fendouzhe crew relies on an unusual source of energy. Unlike most life at the surface, which depends on sunlight, this hadal-zone ecosystem derives energy from methane, hydrogen sulfide and other compounds dissolved in fluids that seep up from the ocean floor. Chemosynthetic microbes use these energy-rich molecules to convert inorganic carbon into carbohydrates that then support the rest of the ecosystem. Du was the first to observe several species of gastropods, tubeworms, clams and other creatures in these ‘cold seeps’, several of which are likely to be new to science, she says.

“Mengran has made a great contribution to these expeditions,” says Xiaotong Peng, deputy director of the Institute of Deep-sea Science and Engineering, who was also in the submersible. He says Du’s experience in coastal research allowed her to identify species found in chemosynthetic communities while they were still on the sea floor, an important skill for determining the significance of findings. “She has a great passion for deep-sea science, and that is one of the reasons why we can find such amazing phenomena at the sea floor,” he adds.

The discovery prompted the team to change its plans during the 2024 expedition, says Peng. The researchers took the Fendouzhe submersible to search for chemosynthetic ecosystems at more sites, including in the nearby Aleutian Trench.

Du, who was the chief scientific officer for the expedition, and her colleagues completed 24 dives in the submersible, which last an average of around 6 hours. Built out of titanium to withstand crushing pressures of 98 megapascals — about 1,000 times the air pressure at sea level — the submersible has an area for the crew that is just 1.8 metres and holds three people.

This year, Du, Peng and their colleagues conducted expeditions to another trench in the southern Pacific Ocean, where they found ecosystems that are similar to those they found in the northern part of the ocean last year. This offers strong evidence that there is a global corridor of chemosynthetic ecosystems across Earth’s oceans, say the researchers.