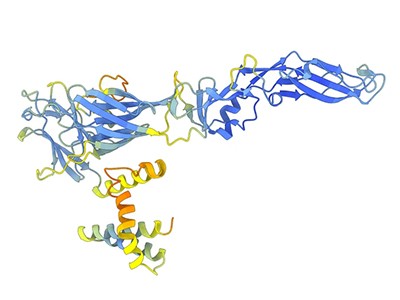

Acanthamoeba polyphaga mimivirus (artist’s impression) is a giant among viruses, both in physical size and because of the size of its genome. Credit: Nanoclustering/Science Photo Library

Scientists report that a type of giant virus multiplies furiously by hijacking its host’s protein-making machinery1 — long-sought experimental evidence that viruses can co-opt a system typically associated with cellular life.

The researchers found that the virus makes a complex of three proteins that takes over its host’s protein-production system, which then churns out viral proteins instead of the host’s own.

Virologists had already suspected that viruses could perform such a feat, says Frederik Schulz, a computational biologist at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California, who was not involved with the work. But the new findings, published in Cell on 17 February, are an important confirmation. Compared with other viruses, he says, this one “has a more powerful toolbox to really replace what the host is doing”.

Big microbe

Giant viruses, which are so named for their massive genomes, might seem exotic, but they are decidedly commonplace. They tend to infect single-celled organisms called protists — a group that includes amoebae and protozoa — that “are all over the place”, says Eugene Koonin, an evolutionary biologist at the US National Center for Biotechnology Information in Bethesda, Maryland.

Scientists glimpse oddball microbe that could help explain rise of complex life

The giant DNA virus used in this study, Acanthamoeba polyphaga mimivirus, has a genome that is about five times larger than those of poxviruses, which have the biggest genomes of any virus that infects humans. Mimivirus is giant in another way too: it is large enough to be seen under a light microscope.

To understand whether the virus affects its host’s protein-assembly line, the researchers isolated viral proteins that interact with host organelles called ribosomes. These structures translate RNA molecules into proteins.

Viral imitation

The scientists identified three viral proteins that seemed likely to be involved in hijacking host protein production. They then genetically engineered the viruses to lack these proteins and found that viruses that were missing any one of the three multiplied 1,000–100,000 times more slowly than those that did have these proteins.

Where did viruses come from? AlphaFold and other AIs are finding answers