Women in the History of Quantum Physics: Beyond Knabenphysik Edited by Patrick Charbonneau et al. Cambridge Univ. Press (2025)

Have you ever doubted your knowledge or expertise? Noticed, if you’re a woman, that you receive less recognition than your male colleagues do, that your ideas were unheard in a discussion until they were echoed by a man — who then received credit for them? Have you observed a gendered division of labour in your workplace; a pay gap; gender, racial or class prejudices? Have you felt pressured to choose between being a wife, a mother and a scientist? Most women in science have.

Against the odds: 12 women who beat bias to succeed in science

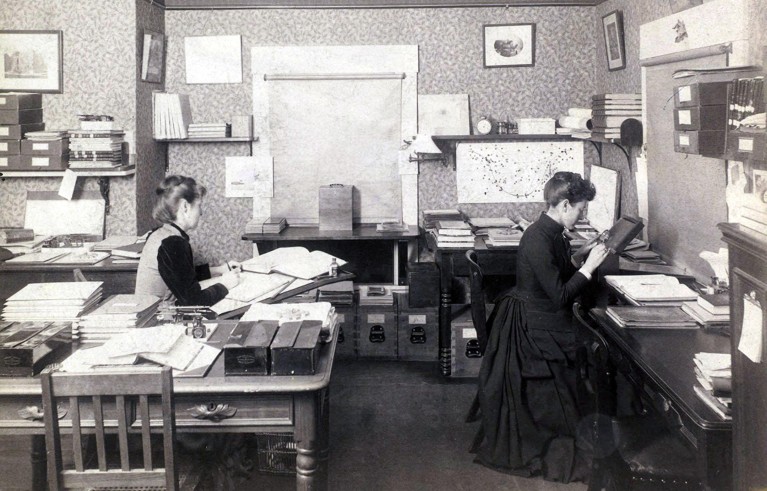

One such scientist was Scottish astronomer Williamina Fleming. She had moved to Massachusetts with her husband, James Fleming, in 1878. Soon after, he left her — pregnant and alone in a foreign land. To survive, she found work in the household of Edward Pickering, director of Harvard College Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His wife, Lizzie Sparks Pickering, recognized Fleming’s scientific aptitude. The observatory employed Fleming in 1881 as one of its ‘computers’ — a role only women could have, under the institution’s strict gender division of labour. The women performed extensive calculations and difficult spectral classifications that provided insights into the physical nature and composition of stars.

Rather than directing her own studies, Fleming performed repetitive tasks, prepared research by her male colleagues for publication and edited the observatory’s reports and articles. Nevertheless, she discovered a set of spectral lines from a helium ion found in the spectrum of hot stars that later became instrumental evidence for extending Danish physicist Niels Bohr’s model of the atom beyond neutral hydrogen. Yet, rather than bearing her name, the set is known as the ‘Pickering series’. Fleming died of pneumonia in 1911. An immigrant, a woman, a mother and an astronomer, she deserves a place in the history of quantum theory and astronomy.

Williamina Fleming (right) was instrumental in the discovery of several types of star.Credit: Science History Images/Alamy

Fleming is one of 16 pioneers recognized in Women in the History of Quantum Physics, an insightful, meticulously researched collection of essays edited by physicists Patrick Charbonneau and Margriet van der Heijden, science writer Michelle Frank and historian of science Daniela Monaldi. In highlighting the contributions of women from diverse backgrounds and nationalities, this bold anthology rewrites the history of quantum physics and challenges its image of Knabenphysik — or boys’ physics, as it became known as in the 1920s because of the prominent work of a small group of young men, including Paul Dirac, Werner Heisenberg, Pascual Jordan and Wolfgang Pauli. The name reflects the view that took hold in a generation of physicists, regardless of their gender.

The people behind the science

The book invites readers to explore what I call a situated–relational history of physics. Situated because researchers viewed themselves, scientific contributions and the field of quantum physics through the lens of their own subjectivity, experience and social position. And relational because knowing how physicists interacted with people, experiments, theories, objects and institutions can help us to understand them and their contributions.

Black women on the academic tightrope: four scholars weigh in

For example, the book shows that to fully understand the research that earned US physicist John Clauser the 2022 physics Nobel prize, one needs to also understand the work of Chinese–US experimental physicist Chien-Shiung Wu. In the 1970s, Clauser performed experiments on entangled photons, in which particles of light become inextricably linked. But in 1950, together with her graduate student Irving Shaknov, Wu had already published what later became recognized as the first documented experimental evidence of entanglement between photons. In the 1970s, Wu turned to experimental philosophy and, together with her student Leonard Kasday at Columbia University in New York City, performed a technically improved version of the 1950 experiment to test local hidden-variable theories in quantum mechanics. Clauser and Wu’s paths intersected in the quantum foundations. Clauser’s criticism of the Columbia group regarding their assumptions and experimental design reveals the greater complexity Wu and her team brought to quantum philosophy. Yet quantum history remembers Clauser more prominently than Wu.

Hurdles and perseverance

As historians, we too need to acknowledge our involvement in the histories we write. We must consider what we might have overlooked because of who we are and our situated knowledge.

The book gives the field of science history a challenge. How do the experiences of these quantum women support or upset our previous knowledge and our historical, sociological and philosophical theses? Until now, we have only had a partial history of quantum physics. This anthology invites historians, and readers, to keep searching for a more complex and situated–relational picture.