Staphylococcus bacteria are responsible for many infectious diseases.Credit: Steve Gschmeissner/SPL

Paul Jensen, a microbial-systems biologist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, wanted to see whether artificial intelligence (AI) tools, such as large language models, could synthesize research on different microorganisms. So he located all the relevant papers on a bacterial species that his laboratory studies — an organism that causes tooth decay called Streptococcus sobrinus — but discovered that he’d already read all of them, a few dozen in total.

Many microbiologists will be in a similar position — or worse. In a study posted on the preprint server bioRxiv last week1, Jensen found that just 10 bacterial species account for half of all publications, whereas nearly three-quarters of all named bacteria don’t have a single paper devoted to them.

“We’ve learnt a lot about a small number of species,” Jensen says. But “for a lot of bacteria, there’s nothing for a language model, for an AI to read”. The microbes important for human — and Earth’s — health are especially understudied, researchers say.

Model microbe

Like other life scientists, microbiologists study model organisms, in the hope that insights gleaned from well-behaved lab darlings such as Escherichia coli will be relevant to other organisms.

In many cases they are: the foundations of molecular biology are built of experiments in E. coli. But as scientists expand the catalogue of microbial life with every skin swab, poo or soil sample they sequence, the chance to uncover new and unusual insights grows.

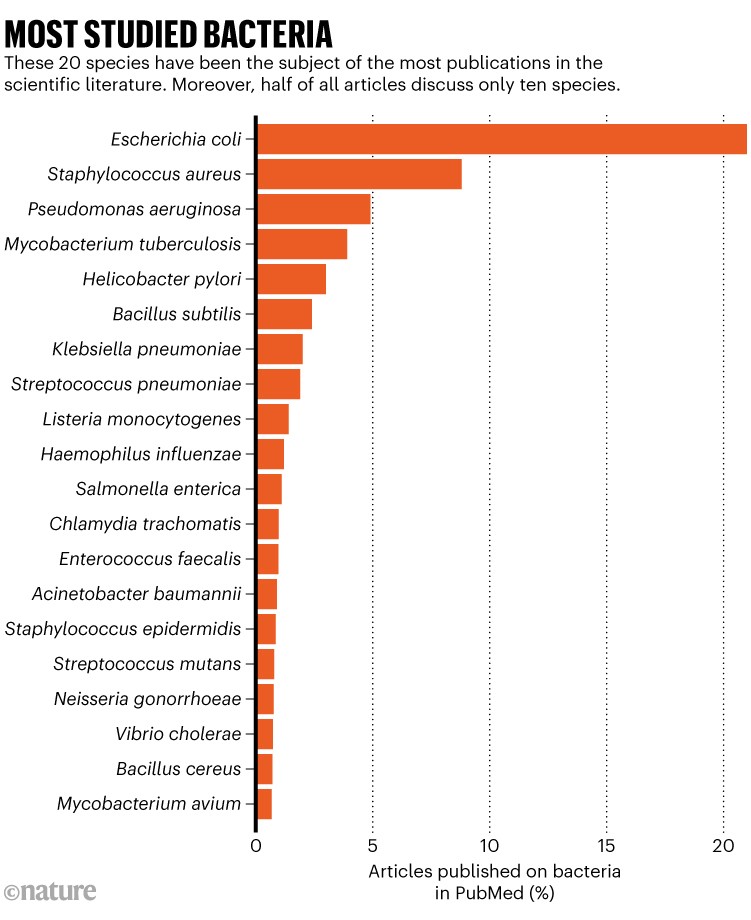

Source: Ref. 1

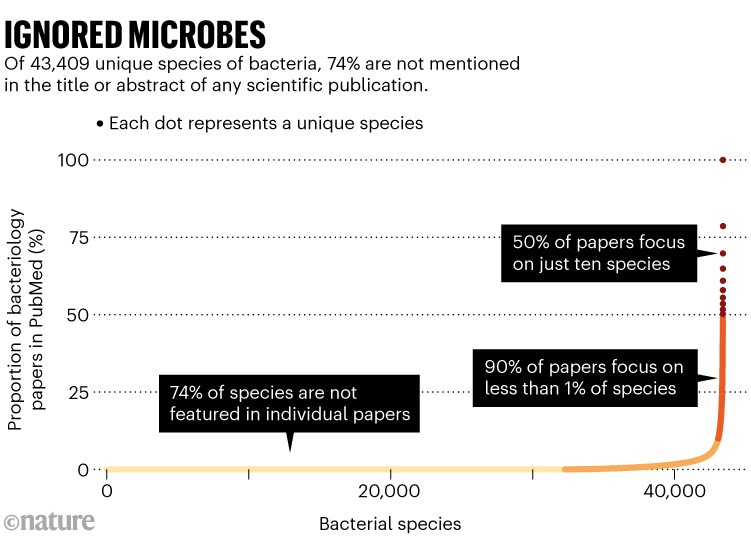

To quantify microbiology’s bias towards a small number of model organisms, Jensen consulted a database of 43,409 unique bacterial species and counted the number of papers indexed by PubMed — a US government-run biomedical literature repository — that mentions each species in the title or abstract.

Unsurprisingly, E. coli came out on top with more than 312,000 publications, 21% of the total. The rest of the top 10 consisted mainly of human pathogens, such as Staphylococcus aureus, an opportunistic infection, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Helicobacter pylori, a stomach microbe that can cause ulcers and even cancer (see ‘Most studied bacteria’).

But 74% of bacterial species were not mentioned in the title or abstract of any indexed paper (‘Ignored microbes’). And the gap between known and studied bacteria has also grown wider in the past 25 years, owing in part to microbiome studies that sequence microbes en masse.

Understudied organisms

Nicola Segata, a microbiome scientist at the University of Trento in Italy, is dismayed by the study’s conclusions — but not surprised. With one or two exceptions, microbes abundant in healthy human microbiomes don’t crack the list of the 50 best studied bacteria. And many organisms important to human health that Segata and others have found haven’t even been named, let alone studied. “These species still have a long way before they will be studied at the level they deserve,” he adds.

Microbes found in diverse ecosystems, such as in oceans and soil, are also conspicuously understudied, notes Brett Baker, a microbial ecologist at the University of Texas at Austin. “None of the dominant organisms in nature are on this list,” he says. “That’s a problem.”

Source: Ref. 1