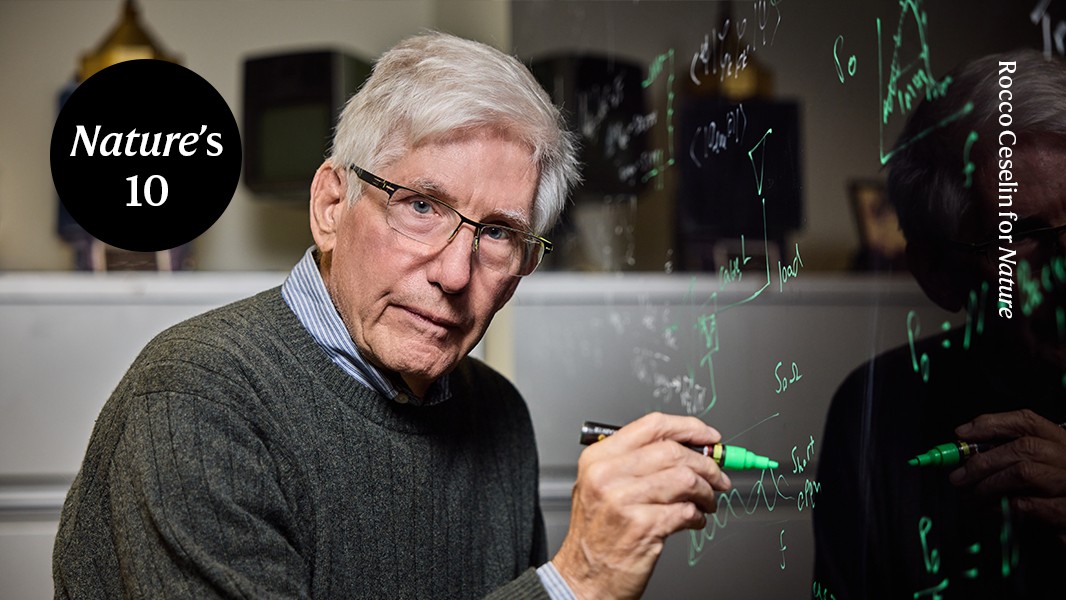

Earlier this year, Tony Tyson got a sneak preview of the first images taken by the brand-new Vera Rubin Observatory in Chile — a project he first dreamt up more than 30 years ago. After he and his team had spent months troubleshooting the telescope’s hardware and control software, thousands of galaxies came into perfect focus. “It’s one thing to know that everything is working, but it’s another thing to see it with your own eyes,” says Tyson. “When I saw that, I said ‘wow’.”

From its perch on Cerro Pachón in the Andes, the Rubin observatory will soon use the largest digital camera in the world to begin making a continuous video of the southern sky. Despite weighing some 350 tonnes, the telescope has a compact design that allows it to move nimbly, capturing a different exposure every 40 seconds. It will map the Universe’s invisible dark matter in 3D, detect millions of pulsating or exploding stars and spot asteroids that could threaten Earth.

Its unprecedented design and the US$810-million cost made the Rubin a huge bet. “It was high-risk, high-reward. We took the risk,” says Tyson, a physicist at the University of California, Davis.

Tyson not only conceived the project, but also pushed it forwards, despite early scepticism. “We wouldn’t have the Rubin Observatory today if he hadn’t had that vision, and also that dogged determination,” says Catherine Heymans, an astrophysicist at the University of Edinburgh, UK, and the Astronomer Royal for Scotland.

Tyson’s interest in science, and building electronic devices, started early. When he was five, a bout of pulmonary disease and rheumatic fever forced him to spend many hours in a steam tent, where he listened to shortwave radio. This experience, he says, kick-started his lifelong interest in getting information out of noisy signals. He also had an early interest in the science of gravity.

Soon after earning a PhD in physics, he joined AT&T Bell Labs in Murray Hill, New Jersey, in 1969. He worked on an early gravitational-wave detector, and then took an interest in charge-coupled device (CCD) sensors — which had just been invented “down the hall”. He realized that the devices’ ability to sense even tiny amounts of light could transform astronomy. He set out to use these sensors to reveal even the faintest, most distant galaxies.

Tyson’s ultimate goal was to image large swathes of the sky, measuring how galaxies’ shapes distorted as their light travelled across a Universe filled with immense lumps of dark matter. He started applying for telescope time to search for the effect in 1973. “I got turned down time after time,” he says.

“A lot of people didn’t think it was possible”, particularly from the ground, says Heymans. But in 2000, Tyson was one of the first researchers to use the technique, called ‘weak gravitational lensing’, to reveal the presence of dark matter (D. M. Wittman et al. Nature 405, 143–148; 2000).

Meanwhile, Tyson continued to use CCDs to build larger and larger digital cameras for telescopes. One that he built in the early 1990s with physicist Gary Bernstein, his postdoc at the time, was installed at a US telescope in Chile and was a key tool in the 1998 discovery of dark energy. While working on that telescope, Tyson got the idea for the Rubin telescope, which he led from the first proposal in 2000 until the main mirror was on its way to completion. He still holds the role of chief scientist, managing the tune-up of the complex apparatus.