January is peak gym time — the month when fitness seekers commit to New Year’s resolutions. By February, however, those goals are often forgotten. That busting of best intentions begs the question: how much exercise do people really need, and what’s the ideal way to get it? Recent research fortunately has some welcome advice for the time-stressed in 2026.

Why is exercise good for you? Scientists are finding answers in our cells

Existing guidelines from most national and global health organizations call for at least 150–300 minutes of moderate physical activity each week, or 75–150 minutes of vigorous activity, for healthy adults, sometimes alongside activities to strengthen muscle and bone. Although those guidelines remain good goals to aim for, newer studies suggest that meaningful health benefits emerge with much less exercise.

Researchers are getting a clearer understanding of the bare minimum amount of exercise needed for health gains thanks to data from wearable devices. These can provide more-reliable measurements than do self-reported data, which form much of the basis for current guidelines. By incorporating wearables into study design, researchers can collect accurate data on physical activity minute by minute, says I-Min Lee, an epidemiologist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts. “And this is when we start to see that even low levels of physical activity are helpful,” she says.

These data are redefining what counts as physical activity and could push future recommendations towards lower targets. But a potential shift in guidelines needs to be considered carefully in terms of the message it might send, says Emmanuel Stamatakis, a researcher specializing in physical activity and population health at the University of Sydney, Australia. No one wants to suggest that people shouldn’t strive to move more, especially when an estimated 31% of people worldwide don’t meet existing recommendations1, and physical inactivity contributes to health problems such as obesity and heart disease.

“We’re in a bit of an awkward situation because if we are to take the wearable-based evidence at face value, we will have to release guidelines that will be recommending lower amounts” of minimum physical activity, says Stamatakis.

Another way in which wearables are changing thinking is by helping to quantify daily inactivity, which might be just as important as how much a person exercises. Some guidelines are already incorporating caps on sedentary time. “Especially if you work from home, you can do very little exercise in a day. It’s quite scary,” says Carol Maher, an exercise researcher at the University of South Australia in Adelaide.

The more, the better — up to a point

Today’s exercise recommendations are born from large epidemiological studies that compare disease and death rates between those who are more and less physically active. Whereas previous guidelines had focused on enhancing athletic performance and relied mostly on studies in young and fit male medical students, studies beginning in the 1980s followed larger groups of people over many years and included women and older people.

Such studies have consistently shown that physical activity offers strong protection against cardiovascular disease, reduces the risk of several types of cancer and lowers the risk of death from any cause, as well as having mental-health benefits. Although observational studies can be limited by potential bias — those who exercise might be healthier to start with — researchers go to great lengths to mitigate this problem. Studies tend to control for variables such as age, smoking status, alcohol consumption and body weight, and adjust for family history of cardiovascular disease and cancer, as well as postmenopausal hormone use, sleep duration and other factors. Some studies exclude participants diagnosed with cardiovascular disease or cancer and those who do not engage in any physical activity. Some also exclude the first years of observation, so that participants with as-yet-undiagnosed diseases can be identified over time. The biases alone cannot explain the findings, says Lee.

Alzheimer’s decline slows with just a few thousand steps a day

A 2011 meta-analysis found that people who met the recommendation of 150 minutes of moderate physical activity a week — defined as movement that raises heart and breathing rates — had a 14% lower risk of coronary heart disease than those who reported no physical activity in their leisure time2. Such moderate activity, during which the exerciser can still talk but would struggle to sing a song, includes brisk walking and light cycling. Those who exercised even more, about 300 minutes a week, had a 20% lower risk than those who didn’t exercise. Heart benefits continued to increase with more exercise, although gains tapered off at higher levels.

Notably, even people exercising for half the recommended 150 minutes a week showed heart-disease risk reductions that were almost the same as for those who met the guideline. The authors concluded that “the biggest bang for the buck for coronary-heart-disease risk reduction occurs at the lower end of the activity spectrum: very modest, achievable levels of physical activity”.

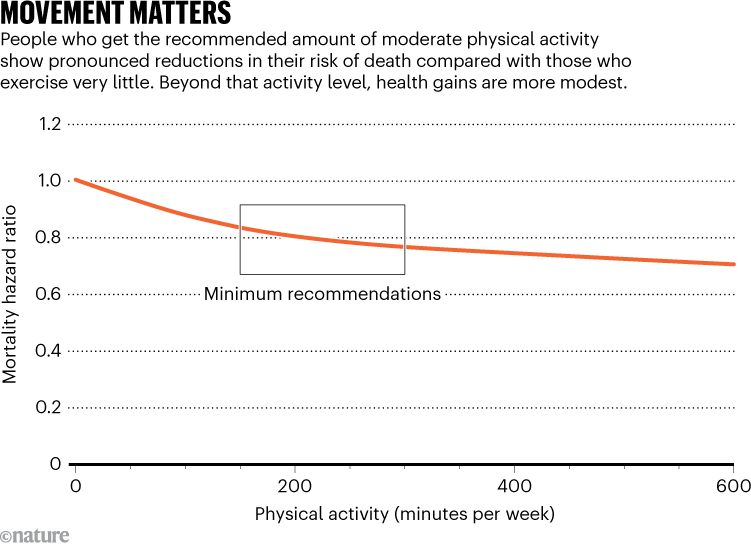

A similar pattern emerges for risk of death (see ‘Movement matters’). A 2022 study analysing 30 years of data from 116,221 adults found that those who did 150–300 minutes of moderate physical activity each week had a 20–21% lower risk of all-cause mortality during the study period than those with almost no moderate activity3. Smaller amounts were already beneficial: 20 to 74 minutes of moderate activity a week resulted in a 9% lower risk of death. People who exercised up to about 600 minutes a week — four times the recommended minimum — had an extra 10–11% reduction in risk. But going beyond that didn’t provide further benefits.

Source: Ref. 3

Lee and her colleagues have also reported, in a meta-analysis published this month that included data from more than 40,000 people, that only five extra minutes of moderate-to-vigorous activity a day could prevent 6% of all deaths among the 20% least active participants. Those participants spent, on average, 2.2 minutes a day in this type of activity4.

“A big part of the benefit comes from going from doing nothing to doing something,” says Leandro Rezende, an epidemiologist at the Federal University of São Paulo, Brazil, and a co-author of the 2022 study.

When it comes to vigorous physical activity — the type of movement that makes speaking difficult, such as cycling uphill or running — as little as 15 minutes each week can be enough to reduce the risk of death. A prospective study, reported in 2022, that followed participants for almost six years revealed that this modest effort resulted in an 18% lower mortality risk over the study period5. The analysis adjusted for how much light and moderate physical activity the participants did overall, as well as other underlying health conditions that could affect their capacity to do vigorous exercise.

Studies using different measures of physical activity come to similar conclusions about the benefits of minimal exercise. A 2019 analysis — which adjusted for factors such as self-rated health and family history of diseases — concluded that, among older women, taking 4,400 steps a day (far below the 10,000 steps that many people aim for) is already associated with a lower mortality risk6. Benefits levelled after 7,500 steps a day. Although there isn’t an exact correspondence between number of steps and minutes of activity, another study using accelerometer data from around 3,500 people found that those who reached 150 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity in a week typically accumulated around 7,000 steps a day (including from intentional exercise and everyday activities)7.

Exercise snacks

The introduction of wearables opened the door to studying exercise sessions that are shorter than 10 minutes, as well as lighter physical activity. Stamatakis is among those who began investigating the effect of short bursts of vigorous activity in people’s daily routines.

He says that he has loved movement since his childhood in Greece, when he spent hours playing football after school. The idea of studying how people can enhance their health with everyday movement occurred to him around 2008. Living in Brighton, UK, he grew sick of the local traffic. “I sold my car, and I started walking everywhere and cycling everywhere,” Stamatakis recalls. “It felt so liberating. It felt so nice. I felt more connected with my community. From that point on, I started converting this into a scientific interest.”

How much protein do you really need? What the science says