You have full access to this article via your institution.

Food insecurity worsened after prices surged during the COVID-19 pandemic and following Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine.Credit: Jonathan Torgovnik/Getty

Of the many faltering goals under the umbrella of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), one target did at least look achievable. The aim of eliminating malnutrition among children under the age of five might not have been reached by the SDGs’ 2030 deadline, but the trend was going in the right direction.

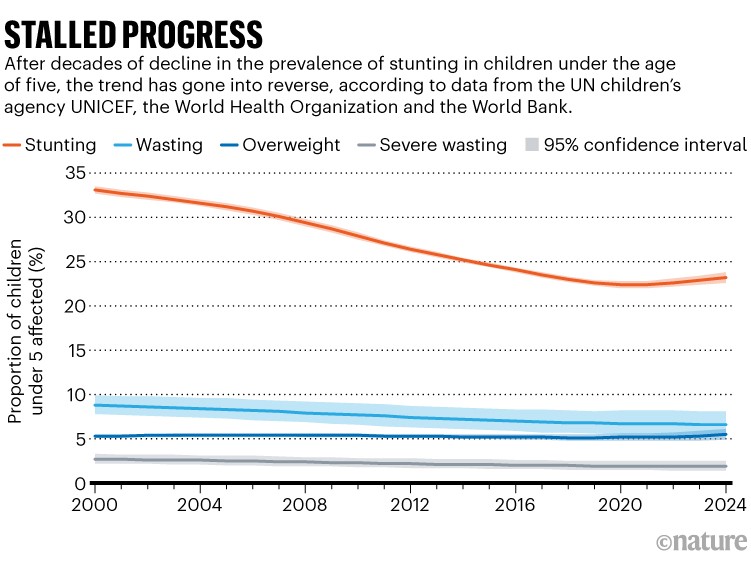

That is no longer the case. In July, an authoritative report called the Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates (JME, see go.nature.com/3jad6db), compiled by the UN children’s organization UNICEF, the World Health Organization and the World Bank, confirmed what many health-care professionals around the world already suspected. Since 2020, there has been an increase in the proportion of children under five affected by stunting (see ‘Stalled progress’). Stunting is one of the main signs of malnutrition, which is defined as deficiencies, excesses or imbalances in nutrient intake. The rise in the prevalence of stunting is a shocking finding, not least because it is a reversal of decades of steady decline.

Source: UNICEF

The question of why so many of the youngest children are not getting enough of the right kind of food should have been a priority for the health leaders who met this week for the World Health Summit in Berlin — yet it wasn’t. This was a missed opportunity, but it isn’t too late to address the problem. Researchers and policymakers must work to better understand what is happening and use this knowledge to act, and act quickly.

Malnutrition manifests in a number of ways. Stunting describes a child who is markedly shorter than expected for their age; wasting describes one who is too thin for their height. Being overweight is also a form of malnutrition, because it increases a child’s risk of developing diet-related non-communicable diseases later in life.

Hunger and famine are not accidents — they are created by the actions of people

The JME report shows that stunting affects around one in three under-fives in South Asia and East and West Africa, and two in five in Central Africa. The figures for Europe, Latin America and North America are much lower, although many countries in these regions seem to have stopped collecting data, so the situation might be worse than it seems to be.

Stunting results from chronic or recurrent malnutrition. Affected children are more prone to disease, perform less well at school and are more likely to have chronic diseases. Wasting is more likely to happen if a child suddenly stops getting sufficient calories, and the consequences can include death. It can be reversed, but stunting is largely irreversible: a child cannot recover their height in the same way that they can regain weight.

The JME report shows that the increase in the prevalence of stunting coincides with the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. The intervening years have also seen the commencement of several armed conflicts. Conflict is a known driver of malnutrition, and some of the nations in which the prevalence of malnutrition is highest are dealing with active conflict or its aftermath.

Imagine a world without hunger, then make it happen with systems thinking

The pandemic had a widespread impact: while countries focused on fighting COVID-19, they diverted resources away from routine but essential health services, such as efforts to tackle malnutrition. Moreover, many people lost jobs as a result of lockdowns, and, at the same time, food prices increased, making food increasingly unaffordable. The report doesn’t examine the relationships between these and other factors, or their role in malnutrition, but it’s clear that answers are needed so that policymakers can work to halt and reverse the current trend. This is where researchers, from health-care economists to nutritionists to health-policy analysts, could make a difference.

It is important, for example, to better understand how increases in stunting are linked to food price rises. Globally, median food-price inflation surged from 2.3% in December 2020 to 13.6% in January 2023, according to The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World report, which was published this year by a consortium of UN agencies, including the WHO and the Food and Agriculture Organization (see go.nature.com/48ump2u). During this period, the report finds, food-price inflation was considerably higher than total inflation.

Counting the cost

Some of the reasons why food-price inflation reached such heights are well understood. Prices rose during the pandemic, in part because lockdowns disrupted food supply chains, creating shortages. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine also played a part: Ukraine is one of the world’s main sources of sunflower oil, wheat and maize (corn). What it is less clear is why prices remained high for so long. Some researchers think that suppliers kept prices artificially high to maintain or increase their profits — a phenomenon dubbed ‘seller’s inflation’ (I. M. Weber et al. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 74, 690–712; 2025).

Ending Hunger: Science must stop neglecting smallholder farmers

Scientists must interrogate how inflation affects malnutrition at the level of individual households. The food-insecurity report says that, in under-fives, a 10% hike in food prices is associated with a 2.7–4.3% rise in wasting and a 4.8–6.1% increase in severe wasting. But this knowledge needs to be available at a more fine-grained level to be useful to those looking to implement effective interventions.

Researchers must also assess whether nutrition services are getting back to pre-COVID levels. This and other knowledge will help policymakers to understand longer-term trends in stunting prevalence. It will put them in a stronger position to prepare for future shocks, and give them more idea of how to manage such events. The rise in child malnutrition is not a statistic that can be ignored; the trend needs to be reversed. If decision-makers are unable to achieve this, the consequences will blight the lives of these children for decades to come.