Ellen was on a cycling holiday in September 2023 when her memory and thinking skills began to falter. Riding behind her husband on their bright green tandem bike through the rolling hills of Europe’s Iberian Peninsula, Ellen found herself struggling to follow simple navigation cues.

When she returned home to Missouri, Ellen (who asked that only her middle name be used) underwent a comprehensive evaluation, including a new blood test designed to detect proteins linked to the plaques and tangles in the brain that characterize Alzheimer’s disease. The results confirmed what her friends and family had quietly feared: Ellen was in the early stages of Alzheimer’s, a devastating form of dementia that erodes memory and affects millions of people worldwide.

Nature Outlook: Alzheimer’s disease

Her clinician quickly prescribed her an antibody therapy designed to impede the disease’s progression. Now, Ellen’s cognitive decline has slowed, and she is looking forward to another tandem cycling adventure this year, ahead of her 71st birthday. “We feel really fortunate,” says her husband. The timely diagnosis, accelerated by the speed and convenience of blood testing, enabled prompt treatment that has given Ellen a chance to maintain her quality of life for longer.

Ellen’s experience highlights the growing promise of blood-based testing for Alzheimer’s. By identifying disease-specific biomarkers in the bloodstream, these tests offer a minimally invasive, affordable alternative to conventional diagnostic methods, such as those that involve a lumbar puncture or brain imaging. They enable physicians to swiftly pinpoint the cause of cognitive issues and provide timely interventions that can help to slow disease progression and preserve quality of life.

“There’s really a sense of momentum in the field now,” says Lawren VandeVrede, a neurologist at the Memory and Aging Center at the University of California, San Francisco.

Yet, obstacles remain on the path to widespread adoption of these tests. Further to working out how they can be integrated into health-care systems, questions swirl around the tests’ real-world performance — not to mention the psychological toll for people who discover they are at risk of a disease that still has no cure.

What’s more, these tests have been rigorously validated for diagnosing Alzheimer’s only in people who are already experiencing symptoms. They are being used increasingly, however, for a range of other applications. These include screening asymptomatic individuals, tracking disease progression and even predicting future risk — uses that, some argue, are outpacing current clinical guidelines and scientific consensus. “The risk we have is asking the blood biomarker to do too much,” cautions Nicholas Ashton, a neuroscientist who leads the biomarker programme at the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute in Phoenix, Arizona.

A tangled history

Alzheimer’s was first described in 1906. For the century that followed, diagnoses were confirmed only after a person died, when clinicians could search a person’s brain for the hallmark plaques of sticky amyloid-β proteins and tangles of tau proteins.

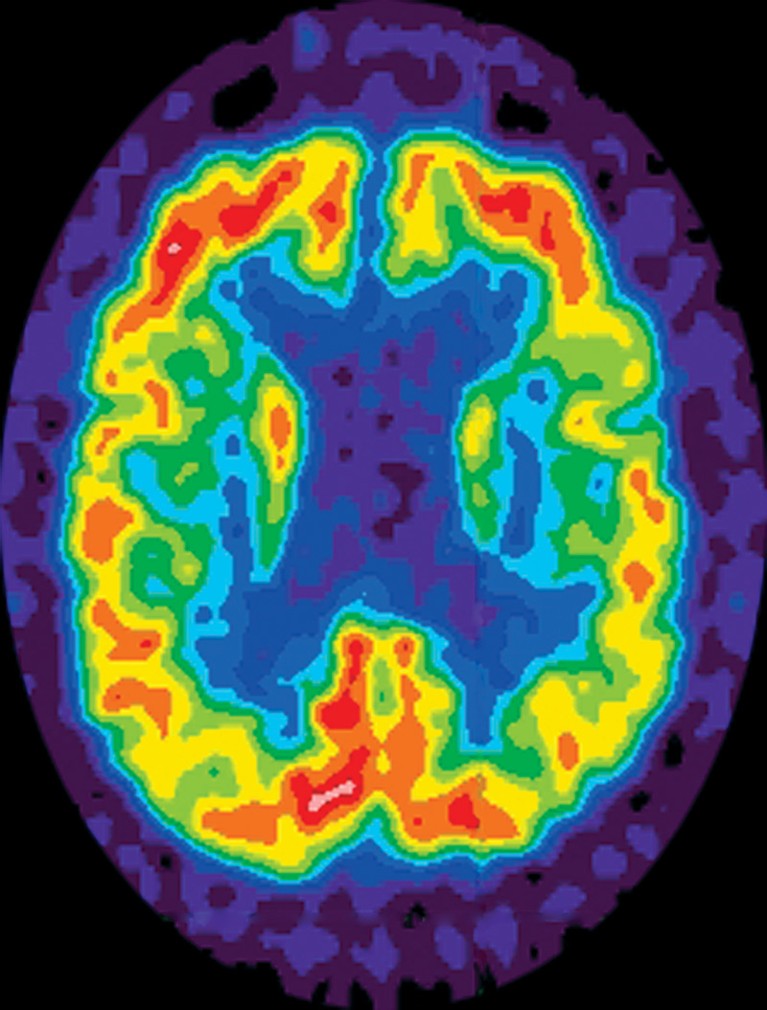

Eventually, methods emerged that allowed for more definitive diagnoses during a person’s lifetime. In the 2000s, clinicians began to test cerebrospinal fluid for disease-related biomarkers — an invasive and uncomfortable procedure, but one that most people can withstand. The next decade saw the rise of neuroimaging techniques such as positron emission tomography (PET), which enabled non-invasive visualization of amyloid-β plaques in the brain.

Yet, these diagnostic techniques remain costly, are often slow and are not available to everyone. As a result, neurologists have continued to rely heavily on clinical assessments, such as memory tests and observing behaviour — methods that leave ample room for error, particularly when distinguishing Alzheimer’s from other forms of dementia.

A large study1 conducted in Sweden underscores the point. When relying solely on physical examinations, cognitive testing and brain scans that can find structural changes such as brain shrinkage but not plaques and tangles, dementia specialists correctly diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease 73% of the time, whereas primary-care physicians had an accuracy of only 61%. By contrast, one of the latest commercial blood tests — designed to measure minute levels of amyloid-β and tau that have exited the brain and begun circulating in the bloodstream — was more than 90% accurate at identifying Alzheimer’s-related pathology.

“It turns out that doctors like me are not very good,” admits co-author Suzanne Schindler, a neurologist at Washington University in St. Louis’s School of Medicine in Missouri. That’s why the rise of quick, minimally invasive blood-based tests for Alzheimer’s is so transformative, she says. “These tests are really helpful in telling us whether people have this in their brain.”

When researchers first started exploring whether blood tests could help to identify individuals with Alzheimer’s, about 25 years ago, the results were underwhelming. The analytical tools available at the time lacked the necessary sensitivity and precision, resulting in inconsistent and often inconclusive findings. It wasn’t until higher-sensitivity assays emerged in the 2010s that consistent and predictive results began to emerge.

A turning point

Advances in mass spectrometry and antibody-based detection methods made it possible to precisely measure even trace amounts of target molecules in blood. Researchers applied these methods first to amyloid-β, then to various forms of tau, paving the way for today’s blood-based diagnostics.

Examining human brain tissue was once the only way to make a firm Alzheimer’s diagnosis.Credit: Westend61/ Getty Images

The arrival of these technologies “was really a turning point”, Ashton says. The results obtained with these improved assays demonstrated consistent, disease-specific changes that could distinguish Alzheimer’s from other conditions. These convinced Ashton that a new standard for Alzheimer’s diagnosis had arrived. “This is not a fad,” he says.

Numerous blood tests that detect various forms of amyloid-β or tau are now approved for use in Japan, the United Kingdom and across the European Union. In the United States, they are offered currently as laboratory-developed tests — a designation that allows for clinical use without full regulatory authorization. However, in the coming months, US officials are expected to give a test the thumbs up for the first time, which could accelerate their adoption.

That product, from a subsidiary of biotechnology company Fujirebio in Tokyo, is one of many that measures a specific ‘phosphorylated’ form of tau, known as p-tau217 — a tau protein that has been modified, as a result of disease, by the addition of a phosphate group to an amino acid at site 217 of the protein.

Duelling diagnostics

P-tau217 is a particularly reliable marker of Alzheimer’s pathology, says Schindler, who led a large comparison of blood tests from seven leading diagnostic companies. The study2, published last October, found that p-tau217 levels reflected the disease state that was visible on amyloid-β PET scans more accurately and reliably than did other variants of tau or amyloid-β in the blood. “The p-tau217 tests are outperforming everything else,” says Schindler, who used one of these tests to help confirm Ellen’s diagnosis. “We just kind of need to get that message out to everyone.”

Many developers of p-tau217 tests are still not satisfied with their accuracy, however. Blood tests for Alzheimer’s are designed to distinguish confidently between people with and without disease pathology, while deliberately allowing for an ‘intermediate zone’ of uncertainty that merits further investigation. However, this diagnostic grey zone is often large. For example, it accounted for more than 30% of all sample results3 determined using a p-tau217 commercial test from Quanterix, a life-sciences company in Billerica, Massachusetts.

To reduce the frequency of ambiguous results, some companies are trying to incorporate extra biomarkers into their tests. Quanterix scientists, for example, have created a multi-marker panel that looks for p-tau217 alongside two forms of amyloid-β and two other proteins linked to brain degeneration and injury. The addition of these biomarkers more than halved the proportion of ambiguous results, to less than 15%, while maintaining overall diagnostic accuracy above 90%3.

Context is key

The reliability of test results rests on more than just biological factors, however. Pedro Rosa-Neto, a neurologist at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, and his colleagues reported last year4 that accuracy is heavily shaped by the prevalence of Alzheimer’s pathology in the population tested.

For example, in people with clear symptoms of dementia, blood tests can confidently identify Alzheimer’s disease. The same goes for adults over the age of 80 who have less severe cognitive impairment. However, in younger people with only mild cognitive issues — a population in which neurological problems are less likely to be caused by Alzheimer’s — Rosa-Neto’s team found that although blood tests are effective at ruling out Alzheimer’s disease, they are less dependable for confirming it. “The interpretation of the test depends on the context in which it’s going to be applied,” Rosa-Neto says.

In Ellen’s case, the interpretation was straightforward — her blood-test results were “as clearly positive as it gets”, Schindler says. Paired with her consistent symptom profile, Schindler and her team determined that Ellen should begin antibody therapy immediately. But such confidence in blood biomarkers is not yet the norm. Most clinicians and insurance companies still rely on extra tests to confirm the diagnosis and assess treatment eligibility.

Positron emission tomography scans are used to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease.Credit: Steven Needell/Science Photo Library

“I’m hopeful that we’ll get to the point where this biomarker stands alone,” says Alicia Algeciras-Schimnich, a laboratory-medicine specialist at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. To get there, she and her colleagues are validating the real-world performance of these assays to ensure that they meet the standards needed for broader clinical adoption. As part of this effort, every person undergoing cerebrospinal fluid testing or receiving an amyloid-β PET scan at Mayo Clinic’s Alzheimer’s treatment centre is invited to provide a blood sample that researchers can use to assess the p-tau217 test.

Such research is crucial because most studies on Alzheimer’s blood tests have been conducted in cohorts that are typically healthier, wealthier and less ethnically diverse than the general population, says Chinedu Udeh-Momoh, a neuroepidemiologist at Wake Forest University School of Medicine in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. “These tests have not been fully tested and validated within diverse contexts,” she says.

Limited research in more diverse populations has revealed that sex, race and ethnic group, as well as medical conditions such as chronic kidney disease and hypertension, can affect biomarker concentrations, potentially complicating their interpretation in Alzheimer’s diagnosis. This variability underscores the need for further study, Udeh-Momoh says. “There is still a need to for us to understand the impact of different environmental, social, demographic and health factors on the performance of these biomarkers before they are implemented widely.”

Primary focus

As Alzheimer’s blood tests establish a foothold in specialty clinics, where they are mainly being used to help to diagnose people who are already showing cognitive symptoms, clinicians are increasingly eyeing the potential to expand their use. The next logical step is to introduce the tests to primary-care settings, where they could serve as an initial screening tool for people who are presenting with vague or early-stage symptoms, to determine whether a referral to a specialist is warranted. However, several challenges need to be addressed for this to be feasible, says Jeffrey Burns, a neurologist at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City.

Primary-care physicians will require clear guidelines on how to interpret test results, he points out, and it will be important to ensure that people can quickly access further care when needed. “We’re expecting this to be something that’s used widely in primary care, but it’s going to take a lot of effort,” Burns says. “The tests are ready, but our system is not.”

Another potential use of the tests is in population-wide screening: identifying Alzheimer’s pathology at its earliest stages, before cognitive symptoms emerge. In theory, this might allow for interventions that delay or even prevent the onset of symptoms. However, no treatments have yet proved effective at such an early juncture in the disease, and screening apparently healthy people has its risks.

A positive test result could cause emotional distress, for instance, or make it harder to secure life or health insurance. When a direct-to-consumer blood test arrived in the United States in 2023, enabling anyone to purchase it without visiting a physician first, it was met with fierce criticism from clinicians, who raised concerns about the product’s reliability and the potential for misinterpretation of results. The test must now be requested by a physician.

Blood tests for cognitively healthy individuals have been transformative for researchers seeking volunteers for trials of treatments for pre-clinical Alzheimer’s — the stage when brain changes are under way but symptoms have yet to appear. “It has saved millions of dollars, and made enrolment much, much faster,” says Robert Rissman, a neuroscientist at the University of Southern California’s Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute in San Diego.

Rissman is leading blood-testing efforts for a clinical trial, called Ahead, which is testing whether the antibody therapy lecanemab can slow or prevent cognitive impairment in people with some amyloid-β build up but no cognitive symptoms — the drug is already approved for treating people with mild Alzheimer’s.

In the first two years of the study, when Rissman and his colleagues relied solely on PET scans to determine trial eligibility, more than 70% of prospective participants would be turned away after the scan, owing to insufficient quantities of amyloid-β in their brains. Since introducing blood tests as an initial screening step, less than 30% of people receiving PET scans have been deemed ineligible. The comparative simplicity of blood testing has also made it easier to enrol a more ethnically diverse and representative cohort, Rissman says.

Ahead of the science?

As the use of these blood tests rapidly expands to various applications, including p-tau217 testing offered directly to consumers, some clinicians fear that real-world practice might be getting ahead of the science.

BetterBrain, a start-up company in New York City, integrates cognitive testing with a suite of blood tests that are designed to assess factors such as vascular health, inflammation, metabolism and nutrient status. For an extra fee, users can opt to receive a p-tau217 test, the results of which are interpreted by ‘brain health coaches’ — typically physicians or nurses — who provide personalized treatment and lifestyle recommendations. Follow-up testing and consultations are then available several months later to track whether interventions have led to measurable improvements in markers of brain health.

“We acknowledge it’s a newer use case” of Alzheimer’s blood testing, says BetterBrain co-founder Tom Latkovic. Some say that it has not yet been validated. “Are we expecting a blood biomarker to be sensitive enough to track change over time?” asks Ashton. “I don’t think we have the evidence for that.”

More from Nature Outlooks

Still, Latkovic stands by the decision to offer p-tau217 testing — responsibly, he argues, as part of the company’s broader, comprehensive brain-health assessment programme — even before its full clinical utility is established. “Our philosophy is to respect the autonomy and the preferences of the people we serve,” he says.

Some people are even turning to these tests for self-experimentation. Last May, 46-year-old Nicholas from Rhode Island took a tau-specific blood test just before he started a diabetes treatment that studies suggest could delay the onset of Alzheimer’s. With a family history of Alzheimer’s and confirmed genetic risk factors, Nicholas (who requested that only his first name be used) saw the medication as a proactive step towards reducing his chances of dementia in later life — and p-tau217 tests as a way to monitor whether the drug is working.

“I don’t necessarily want to take it if it’s not doing anything,” he says of the diabetes drug. “I think a reduction in my next tau test would be a good enough sign that it’s probably moving in the right direction.”

Whether Nicholas’s approach represents a glimpse of the future or an overreach beyond the test’s intended use remains to be seen. But with blood testing for Alzheimer’s becoming increasingly accessible to consumers and physicians alike — and with an increasing number of disease-modifying therapies securing regulatory approval and entering clinical practice — many people in the field stress the urgent need for the research community to establish clear guidelines on the capabilities and limitations of these tests. “These are things that we need to do as soon as possible,” Rosa-Neto says.