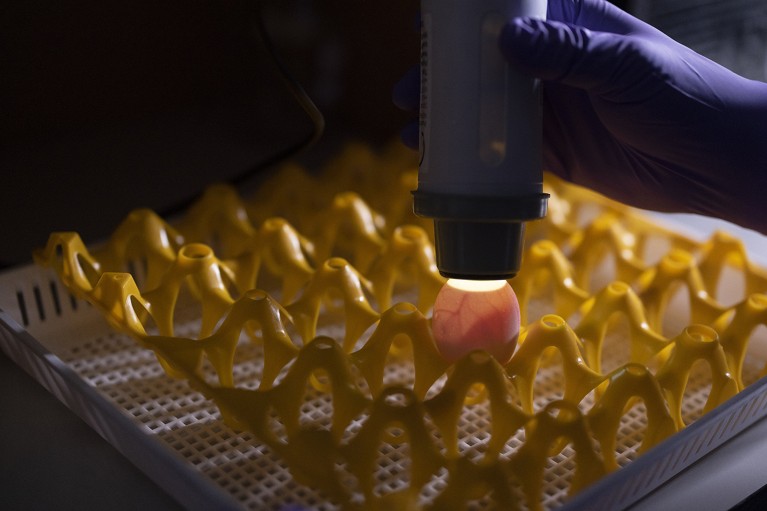

Fertilized chicken eggs are used to manufacture flu vaccines. Credit: Jason Alden/Bloomberg via Getty

During the summer of 2023, fur farms in Finland that raise mink, foxes and raccoon dogs were hit by an outbreak of H5N1 avian influenza. Nearly half a million animals were culled during the outbreak, and Finnish health officials were on high alert. “We worried that under circumstances where many animals are confined in small places, the pathogen might rearrange genetically into a new pandemic virus,” says Hanna Nohynek, a vaccinologist and chief physician at the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare in Helsinki.

Finnish authorities responded by offering to vaccinate groups at high risk of H5N1 exposure, including fur-farm workers, laboratory technicians and veterinarians — the first and only country to do so.

Nature Spotlight: Influenza

This was a precautionary measure: although H5N1 is spreading among birds and other animals all over the world, human cases are still rare. But this state of affairs could change. An H5N1 pandemic “might be the big one that many of us have worried about”, says Ashish Jha, a physician and dean of public health at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island.

The bird-flu shot used in Finland was developed by CSL Seqirus in Holly Springs, North Carolina — one of a handful of companies developing vaccines against H5N1. Amassing a global arsenal of vaccines for the virus is a tricky proposition. Like most other influenza vaccines, the shots are manufactured in chicken eggs or cell lines. New batches take up to six months to produce, which is a long wait if a pandemic starts to rage.

And there is no guarantee that H5N1 will ever be a deadly threat. By the time Finland implemented its vaccine programme, having waited until the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in Amsterdam licensed the Seqirus shot in July 2024, the outbreak in its fur industry had ended without a single human infection. “You don’t want to stockpile millions of vaccine doses that you may never need,” says Marco Cavaleri, head of the EMA’s Office of Biological Health Threats and Vaccine Strategy.

Bird flu in brief

There are four basic types of influenza virus: A, B, C and D. Influenza A and B both cause seasonal flu in people, but only the A type has a history of causing human pandemics. The virus is further broken out into subtypes based on two surface proteins. One of the proteins, haemagglutinin, binds to receptors on host cells and has 18 subtypes (H1–18). The other protein, neuraminidase, has roles in the spread of the virus and has 11 N subtypes.

Influenza A viruses circulate in various animal species. And when the virus jumps from birds to humans, the consequences can be deadly. H7N9 bird flu, which emerged in China in 2013 and has so far infected nearly 1,600 people, has a fatality rate in humans of around 40%. Nearly 1,000 people have been infected with H5N1 since 2003, mostly through direct contact with infected animals. Roughly half of the people affected died. Human-to-human bird flu transmission has been documented only in rare instances involving prolonged exposure to a seriously ill person.

The current dominant form of H5N1 — the 2.3.4.4b clade — became widespread after 2018. It has infected a greater variety of birds and mammals than any other known avian flu virus, “which is why it’s so alarming”, says Scott Hensley, a microbiologist who specializes in influenza at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. But the virus doesn’t easily infect people. Only 70 cases of H5N1 influenza, all of them in cattle and poultry workers, have been reported in the United States, as of July 2025.

Most of the infections with this clade have produced mild illness akin to the common cold. The one person who died was over 65 and had underlying health problems. Why the 2.3.4.4b clade isn’t as lethal as its predecessors isn’t clear. “Cross-reactive immunity from prior H1N1 [seasonal flu] infections might play a role, and the route of transmission may also have had an effect,” says Gigi Gronvall, an immunologist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, Maryland. Still, even mortality of one person in 70 “does not bode well for how H5N1 could affect the whole population”, Gronvall adds.

Currently, H5N1 doesn’t bind well with cell receptors in the upper airway of people. But that could change. In 2024, scientists reported1 that a single mutation in the viral genome could enable H5N1 to readily attach to human lung cells. If the virus were able to replicate efficiently in the lung, it would transmit through the air, potentially spawning a large outbreak.

Paul Offit, a paediatrician at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania, describes H5N1 as an unrealized threat that needs monitoring. The good news, he says, is that even after almost 30 years, the bird virus still doesn’t readily infect human lungs “and maybe never will”. But with repeat ‘spillovers’ into different species, H5N1 might be edging closer to a random mutation that facilitates airborne transmission of a pathogen that seasonal-flu vaccines would not protect against.

H5N1 shares sequence similarities with the seasonal-flu virus H1N1. But for vaccination, the genetic overlaps occur in the wrong place. The seasonal shot prompts immune reactions against the ‘head’ of haemagglutinin — the part that binds directly with human cell receptors. H5N1 and H1N1 overlap on the ‘stalk’ part of haemagglutinin. As a result, Hensley says, “you need H5-specific vaccines”.

Amassing an arsenal

Vaccine makers are providing those shots. As well as Seqirus, companies, including GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi Pasteur and AstraZeneca, have developed H5-targeted vaccines for human use in the United States, Europe, Asia and Australia. All the shots are produced in fertilized chicken eggs or mammalian cell lines, with the same processes that are used to make vaccines for seasonal influenza.

According to a March 2025 document published by the non-partisan Congressional Research Service, the United States planned to stockpile 10 million doses of H5N1 vaccine by early 2025. It takes two doses given weeks apart to fully vaccinate someone against a new strain of influenza, according to Jha, so that would be enough to inoculate about 1.5% of the US population.

It’s unclear, however, whether that target was reached, or even whether it remained a goal. When asked, the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR) — the agency that coordinates US responses to and recovery from public-health emergencies — did not confirm the size of the stockpile.

H5N1 remains widespread on US dairy farms and some scientists say that it poses an existential threat to certain wildlife species. But an ASPR spokesperson says that with reports of animal infections declining and no new human cases since February 2025, the emergency bird-flu response put in place by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) had been deactivated, adding that “millions of doses are already filled and could be made available” if that became necessary.

Prominent public-health scientists criticize this move. Given these cuts, Offit says, “I’m concerned that we won’t have enough vaccine doses should a pandemic occur”. Peter Hotez, who directs the Center for Vaccine Development at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston, says that this latest decision reflects a “broader absence of situational awareness and pandemic preparedness” by the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

Elsewhere, preparations for an H5N1 outbreak are taking place. Fifteen European Union countries have collectively stockpiled 665,000 doses of the same Seqirus vaccine that was made available in Finland. The shots were authorized through an EMA programme that makes vaccines available to protect high-risk individuals “in case H5 strains start getting worse”, Cavaleri says. Seqirus has further contracts to provide millions of doses to the United Kingdom, the United States and the Asia Pacific region, according to Ray Longstaff, the company’s director for pandemic preparedness and response in Maidenhead, UK.

The zoonotic shot targets the 2.3.4.4b clade of the variant H5N8, which is closely related to H5N1 but has not spread as far. H5N8 isn’t typically encountered in people, but it has been detected in several animal species and is widely distributed in birds. Blood samples from volunteers who were vaccinated with the shot produce immune antibodies against H5N1 in lab assays. According to an EMA report of experimental results, between 64% and 90% of people produce antibodies that prevent infection in sufficient amounts to protect against a variety of H5N1 clades — including some that were common decades ago.

Nohynek and her colleagues in Finland tested the Seqirus zoonotic vaccine specifically against the 2.3.4.4b clade of H5N1 and found that 83–97% of vaccinated volunteers developed enough neutralizing antibodies to ward off infection2.

Meanwhile, European Union countries have signed up to purchase 112 million doses of pandemic-preparedness vaccines manufactured by Seqirus and GlaxoSmithKline. These shots cannot be distributed, however, until a pandemic is declared. Companies want to avoid mass production until they know which virus to target, and this EU agreement ensures that if a pandemic does strike, vaccine manufacturers “can get a rapid approval without additional clinical data”, Cavaleri says.