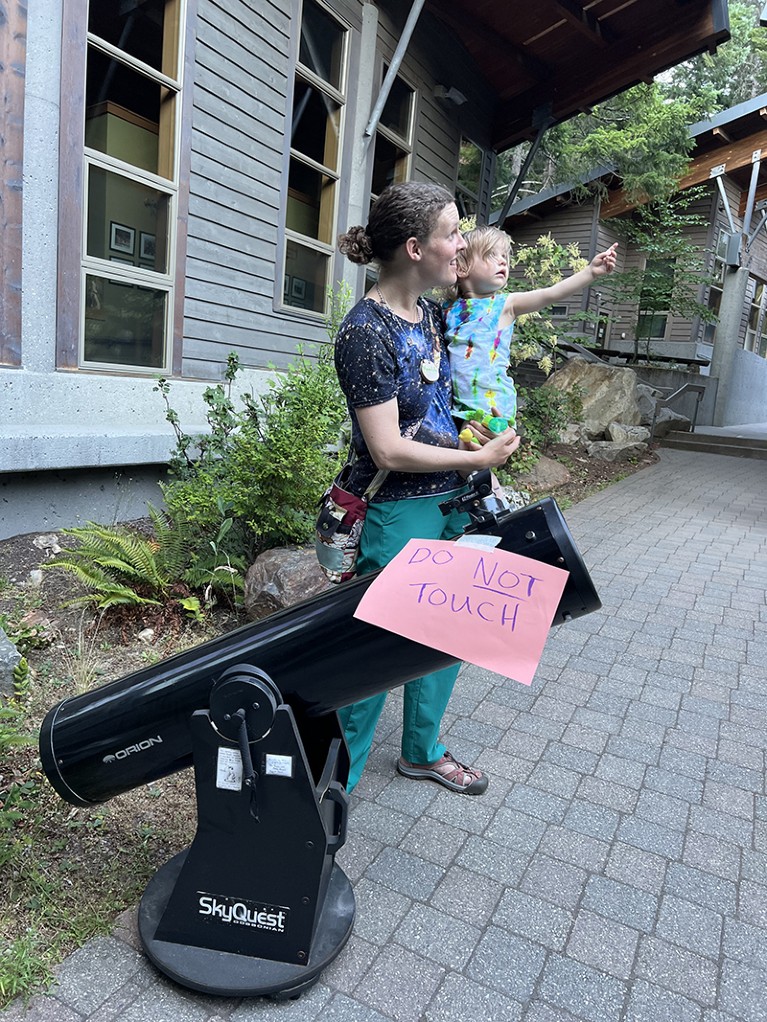

Geographer Mette Bendixen, with her son Bille near Wyoming’s Grand Teton mountains, says her PhD was a flexible time to become a parent.Credit: Lars Lønsmann Iversen

Neuroscientist Ewa Bomba-Warczak knew she wanted to have children, and in the fourth year of her doctoral studies she remembers asking her aunt, “When is a good time?” Her aunt countered with, “When is a bad time?” Others told Bomba-Warczak to wait until she passed her qualifying exams for the PhD or reached another milestone, but she realized there was always going to be a new bar to clear. She became pregnant soon after that conversation with her aunt and defended her thesis at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 2016 when her daughter was four months old. “My mum was taking her around the hallways so she wouldn’t cry,” she recalls.

I had three children during my PhD: here’s what I learnt

Many PhD students find themselves contemplating whether to have a child during their PhD or wait until afterwards. The considerations vary between countries, institutions and individual research groups, depending on graduate-student pay, the cost of childcare, parental leave policies, the length of a PhD, support from colleagues and other factors.

Nature’s careers team asked several early-career-researcher parents how they planned with their advisers and made finances work. “You don’t have to do it exactly how other people do it,” says astronomer Meredith Rawls at the University of Washington in Seattle, who waited until starting her postdoc to have her first child. “You can find your own creative combination of things that works for you.”

Set clear expectations

Bomba-Warczak, now an assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, was the first female student in her PhD laboratory to have a child during her studies, she says. Being a scientist mum was not normalized in her PhD department at Wisconsin: she didn’t even know which professors in the department had children, because they never talked about it.

Bomba-Warczak encountered a pervasive assumption that because she had become pregnant when she was a graduate student, “that means I’m done. I’m going to leave science,” she says. One principal investigator (PI) who wrote her a letter of recommendation for a postdoc position blurted, “Oh no, what are you going to do now?” when they first saw her with her daughter.

Grass-roots pressure grows to boost support for breastfeeding scientists

She pushed back on this narrative by always being vocal about her determination to continue in science. When she sat down with her PhD adviser to discuss her pregnancy, she said, “It’s going to take me longer, but I will get there. My plans have not changed, don’t give up, don’t step away from mentorship.” Her adviser was extremely supportive.

The University of Wisconsin–Madison did not guarantee paid parental leave for graduate students until 2024. So in 2015, her department didn’t know which laws applied to her situation, if any, she says. Bomba-Warczak and her adviser mutually decided that she would take eight weeks of paid leave. For the most part she did not work, but when reviews for a paper came back a couple of weeks into her maternity leave, she responded to those e-mails to keep the publication moving forwards.

By contrast, in Mette Bendixen’s PhD programme at the University of Copenhagen, it was “way more common for women to have a kid during their PhDs than to not”, she says. PhD students at the institution get a year of paid parental leave, and several women had multiple children during their PhDs. Bendixen, who is now at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, had her son in 2014, two years into her three-year PhD programme.

Meredith Rawls with her youngest child.Credit: Mike Bigelow and Meredith Rawls

Bendixen’s geography research involves fieldwork, so she tried to time her pregnancy so that her maternity leave would end just before the summer. But “it took a while for me to get pregnant”, she says, so the baby ended up being due in July and she missed a season of fieldwork. “At the time, it seemed very problematic,” she says, but becoming a parent made her reconfigure her priorities.

When she came back from her parental leave, the first thing she did was apply to work 32 hours a week, a slightly part-time schedule compared with her usual 37 hours, with full support from her supervisor. Having a child “definitely made me reconsider what’s important”, she says. “Academia swallows up your whole life if you let it.” Carving out even five hours a week was a good work–life boundary to set for herself.

Collection: Juggling scientific careers and family life

Bendixen felt that her PhD was a good time to have a child. “A PhD is when you’re the most flexible,” she says. “If you can get five or six good, productive hours [in per day], that’s fine. If the kid is sick, no one’s going to mind if you work from home.”

Bomba-Warczak agrees. She had her second child during her postdoc and experienced more pressure and less flexibility over deadlines than she did throughout her PhD. During a postdoc, “you want to build your network, go to conferences. At times, I was travelling every week,” she says. There are some postdoctoral fellowships, for example through the US National Institutes of Health, that are available only for a limited time — for example, two different fellowships are open to those who are within 18 months or 4 years of receiving a PhD. And although extensions to account for parental leave are available, this increased the time pressure that Bomba-Warczak felt during her postdoc.

Too much PhD pressure

Some early-career researchers, however, found that the pressures of PhD student life were not ideal for starting a family. Priscila Cunha, an ecologist at the State University of Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, found the time spent doing her PhD, when she had her first child, to be less flexible than that during her postdoc, which she did after her second child was born.

Cunha’s first pregnancy was unplanned, and she panicked when she found out, in part because, just a week before, she had received a scholarship to do part of her PhD abroad, at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. “I thought, I’m not going to be able to go,” she says. At first, she told only three people about the pregnancy: her husband, her sister and her adviser, who helped to calm her fears. “I knew that my adviser would understand because she was already a mother of two and was an advocate for women in science,” she says. In the end, Cunha was still able to study abroad for four months.

Ecologist Priscila Cunha did fieldwork for her PhD while pregnant with her first child in 2019.Credit: Eugenia Zandonà

After her son was born in 2019, her programme guaranteed four months of paid maternity leave, but she worked whenever she could to improve her chances of getting a good postdoc position. By contrast, her husband had only five days of leave after their son was born, including the weekend.

The newborn phase was rough for Cunha and her husband. Their son “would only fall asleep in my lap or my husband’s lap, so for months we were like zombies”, she says. The baby struggled with breastfeeding and failed to gain weight in his first month. The early months of breastfeeding were almost as hard for Cunha as completing a PhD, she says, but she persisted. Because Cunha was still attending university classes when she was pregnant, she “had very strict deadlines” for her courses, she says. Fortunately, her mother and mother-in-law watched her son often so she could work.

She graduated from her PhD and her daughter was born in 2022. That year, she applied for postdoc positions and started one at the State University of Rio de Janeiro. Cunha found her postdoc, with its lack of coursework and freedom to focus on research, to be much more flexible for raising a family.

The huge toll that PhD studies take on people’s mental health is well-documented, and for some graduate students, parenting can add to those struggles. Marine geologist and data scientist James Bramante had two children during his PhD at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge. His son was born four months into his PhD in 2015, and his daughter in 2018, a year before he finished.

Juggling research and family life: honest reflections from scientist dads

He was lucky that his three main advisers, all relatively young fathers themselves, were supportive. “When I told my primary adviser,” Bramante says, “his face lit up and he was like ‘Jimmy, this is going to be the best time of your life!’”