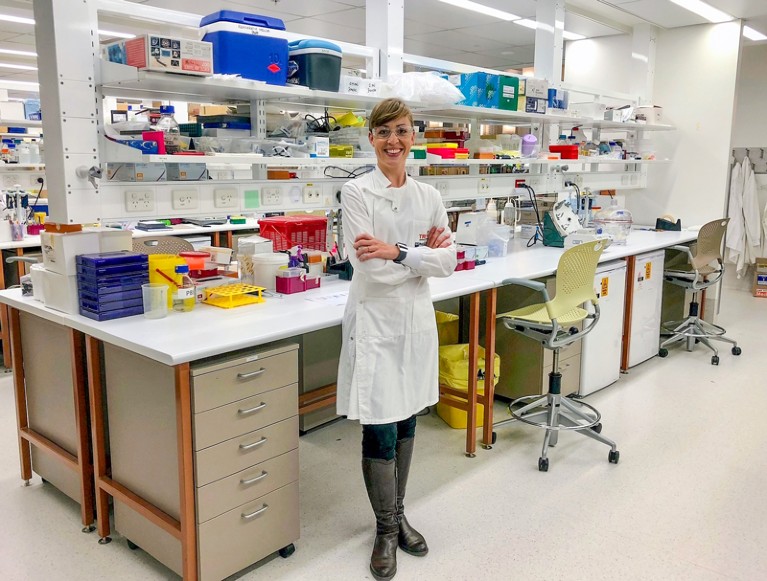

Nathalie Bock and her partner juggled childcare, hospital visits and work commitments after their twin sons were born. Credit: Nathalie Bock

In January 2021, my partner and I were on fixed-term postdoctoral fellowships in Australia when life threw us a rapid sequence of curveballs. We hadn’t planned on four children, but our third pregnancy became twins. Elio, one of our twin boys, was born with intestinal atresia: his small intestine wasn’t connected to his large intestine. A day after birth, surgeons made a life-saving stoma.

Six weeks later, while he was still in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), a biopsy revealed that he had total colonic Hirschsprung disease (TCHD). Elio’s colon would never function, meaning that the stoma bag was going to stay for a few years. Living with TCHD entails chronic diarrhoea, vitamin supplementation and a constant risk of dehydration.

Being in a neonatal care unit is hard at any time, but Australia’s strict pandemic border closures meant that our relatives from abroad — we’re from France and Italy — could not fly in to help. After eight weeks, Elio moved from the NICU to the children’s hospital, where a parent had to remain with him at all times. My partner packed a suitcase; he lived in hospital for another three months while we waited for Elio’s stomal output to stabilize. At home I juggled looking after our two older children, aged five and eight, breastfeeding Elio’s brother Enzo, and a daily 45-kilometre commute between our home and the hospital.

Luckily, our institutions granted us extra personal leave, which helped considerably. Still, we were two materials scientists on fixed-term contracts, now a family of six, including a disabled child. We made a pact: we would be there fully for Elio and would not sacrifice one of our careers to save the other, as many others (typically women) are forced to do. We’d spent years of our professional lives pursuing these career paths and, as stubborn optimists, we believed that with the right mindset we could both keep our careers going. We thought this would be the best way to provide our family with stability and fulfilment. Our plan was the same as those we’d put in place during frantic grant-writing seasons — to take turns advancing our work, to keep both of our research careers alive.

I won three competitive grants in a row. Here’s how I learnt what to do

From March to June 2021, my partner continued with his fellowship — developing sustainable, biodegradable materials for Australian commercial packaging products — while juggling nasogastric feeds, stoma care and baby cuddles. I advanced my fellowship work on the development of new biomaterials that can be used to culture and test cancer tissue in the laboratory, while running the rest of the family, buoyed by the support of my colleagues and friends.

We made it work from June to December. Elio’s disability was not eligible for government support, however, and despite donations from relatives and friends, we couldn’t afford a specialized carer. So, by late 2021, we started trialling the only nursery that would take Elio. His medical team helped us to adapt his daytime feeding so that he no longer needed nasogastric feeds. Nurses trained the nursery staff to empty his stoma bag and give him multiple medications. Soon after, Elio was fully enrolled at nursery: no more isolation and plenty of fun alongside Enzo and the other toddlers. One of our biggest successes as a family.

Then came a new hurdle: how to respond to questions around career disruption on our grant applications. Many Australian funders offer applicants the opportunity to describe their personal circumstances, so that an individual’s track record of research can be judged fairly, which is a well-meaning attempt to balance the playing field for scientists whose careers have been thrown off course by life events.

Nathalie Bock develops biomaterials to study the role of cellular microenvironments in normal and pathological tissue states.Credit: Nathalie Bock

In practice, however, this meant disclosing intimate details about my family’s and my life to people who were unqualified to assess them. This information gets sent to peer reviewers, who are often colleagues, whose expertise is in science, not socio-medical assessment.

When my partner encountered this request in an important grant submission, he chose not to disclose this information. He felt that it was too personal and with hospital life in full swing, he also knew that he didn’t have the capacity to bring this funding application to a more competitive level. He asked a senior colleague, originally a co-investigator, to step up as the lead applicant. The grant succeeded — a collective win — but my partner relinquished leadership.

I felt similarly reluctant to disclose my recent personal trials. As a grant reviewer myself, I had read deeply personal accounts from others that I had no training to evaluate. In our small research community, I would sometimes find myself working with those same researchers who had shared their experiences in their applications. I’ve made the difficult decision to share personal details here to raise awareness of these issues. But, in the context of grant assessment, I doubt any reseacher wants their colleagues to know such details about them.