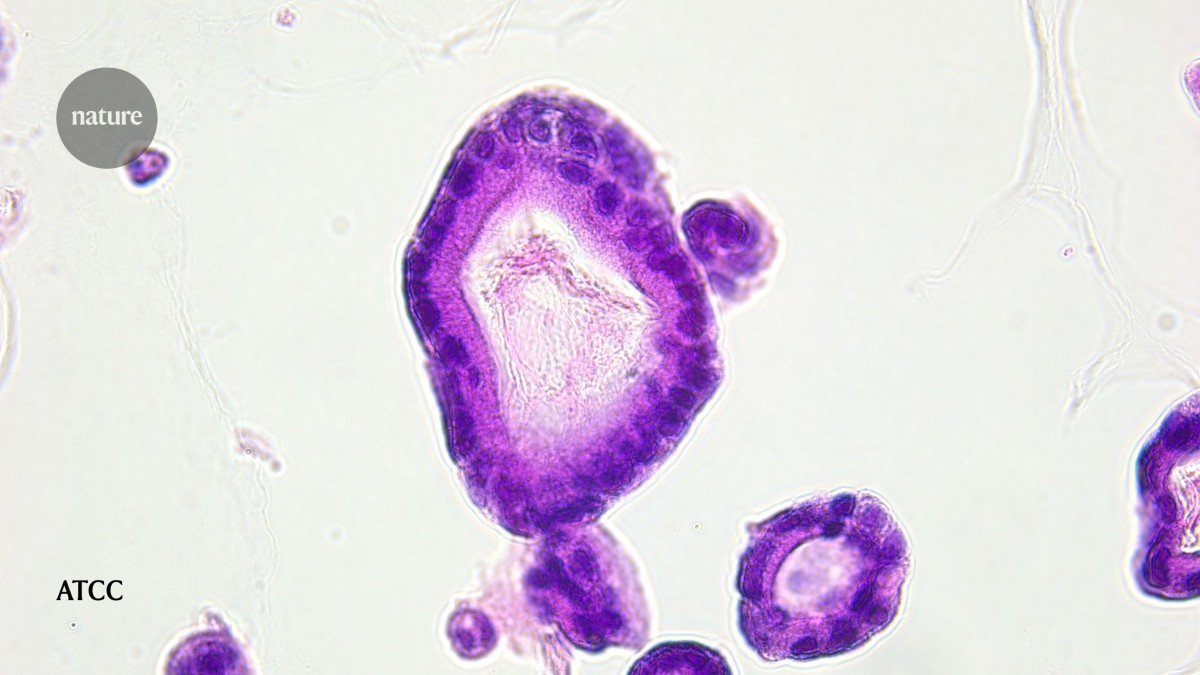

Organoids derived from people with pancreatic cancer can help to determine whether potential drugs will be effective. Credit: ATCC

Christian Pilarsky vividly remembers the moment, in 2022, when he realized that his technique for modelling pancreatic cancer had finally worked. A molecular biologist at the University Hospital Erlangen in Germany, Pilarsky had been struggling for three years to perfect the method, which involves growing miniature 3D replicas of pancreatic tumours derived from a person’s cells. “Trying this and trying that” and correcting errors along the way, he and his colleagues could eventually grow organoids from six out of every ten people they took cells from. The results produced “a kind of happiness only experimental scientists understand,” Pilarsky says. “It’s nearly as good as the moment after a child is born.”

Robust models of pancreatic cancer, such as Pilarsky’s organoids, are increasingly a key component of developing treatments for pancreatic cancer, which has one of the lowest survival rates of all major cancers. Models are used in research to improve treatments and detect the disease before it spreads beyond the pancreas. They are also used to investigate fundamental questions about the cancer’s aggressive nature and its resistance to therapies. Ultimately, they “are a way of understanding the biology of a tumour without doing clinical research on patients”, says Ben Stanger, a gastroenterologist at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. This allows researchers to capture the diversity of pancreatic cancer much more quickly and cheaply than they ever could with older techniques.

Nature Outlook: Pancreatic cancer

Organoids are only one of a growing number of modelling tools. Other experimental systems include specialized animal models that have been engineered to develop pancreatic cancer, or that are injected with human tumour cells. Researchers are also turning to computer models and artificial intelligence to discern patterns in patient records that might help to predict which individuals will go on to develop the disease.

These efforts have the support of governments on both sides of the Atlantic. In Europe, an initiative across nine countries called Pancreatic Cancer Organoids Research, known as PRECODE, has established 13 centres of excellence for organoid research. Since 2020, this has led to at least 80 new pancreatic cancer organoids. In September, the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) announced plans for a centre dedicated to organoid-based modelling, following an earlier US announcement that called for a move away from animal models.

“The disease is tough but not unbeatable, and the models are going to help us win,” says David Tuveson, a cancer biologist at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York. “I’m the most excited I’ve ever been about our field.”

Microtumours and mini-organs

Tuveson has had a front-row view of progress in the field since 2015, when he and his colleagues developed the first pancreatic cancer organoids1. This breakthrough began to address issues that scientists working with pancreatic cancer cells in a dish had been facing for decades: the cells did not represent the complex, 3D nature of how tumours function in a body, says Carolina Lucchesi, head of microphysiological systems at the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) in Manassas, Virginia, a non-profit organization that provides cells and microorganisms for research.

Organoids got around these limitations. Unlike 2D cell lines, their 3D structure preserved the architecture, heterogeneity and drug responses of an individual’s tumour.

In 2018, Tuveson and his colleagues created an entire library of organoids using cells taken from enough people with cancer to represent much of the diversity of the disease, including gene mutations and genes that are turned on or off2. By administering a variety of drugs to the models and comparing the results with patient data, the team found that the organoids responded to chemotherapy in much the same way as the people from whom the cells came. This sealed organoids’ place as a testing ground for treatments. “It was that research that changed the field in terms of how we can use these models,” says Naomi Walsh, a cancer researcher at Dublin City University.

Patient-derived pancreatic cancer organoids now provide researchers with a way to find drugs and gauge how they might work in people. In a study3 published in April, for example, Pilarsky and his colleagues used organoids to test a potential treatment made from a compound found in marine sponges (Xestospongia). They found that the compound inhibited organoid growth, especially when combined with chemotherapy, and that the response varied depending on which mutations the organoids expressed.

Organoids are also helping to reveal why pancreatic cancer is so deadly. In March, researcher Vincenzo Corbo at the University of Verona, Italy, and his colleagues used patient-derived organoids and matched tumours to show that circular fragments of DNA that occur outside chromosomes — known as extrachromosomal DNA (ecDNA) — can carry a specific tumour-promoting gene4. The team found that ecDNA carrying this gene, depending on variations in its expression and number of copies, can cause striking differences between cancer cells in terms of their shape and response to their surrounding environment. The researchers also demonstrated that low levels of ecDNA allow cancer cells to adapt quickly when the environment changes, but that high levels affect the cells’ ability to survive. Therapies could exploit the weakness caused by having high levels of ecDNA or directly target the cancer-driving gene in ecDNA, Corbo says.

Scientists have gleaned much from organoids on their own. However, “we know that cancer doesn’t exist by itself, but is in this microenvironment with all these other cells that are in tune with each other”, Walsh says. Scientists are adding elements to the network of proteins and carbohydrates that organoids are cultured in to mimic this environment. Some researchers are also using specialized devices called organs-on-a-chip that allow cells to grow in an environment that mimics the functional and physiological conditions of human tissues, such as the pancreatic ductal network that transports digestive fluids.

Creating lab-grown pancreatic cancer organoids is time consuming, but researchers are increasingly able to purchase them ready-made. “Just a few years ago, organoids were dependent on a group having access to hospitals and all the resources needed to develop and bank their own cultures,” says Karla Queiroz, a cancer biologist at Mimetas in Leiden, the Netherlands, which develops human 3D disease models. Now, researchers can choose from a growing number of customizable commercial options, she says.

The ATCC, in partnership with the international consortium the Human Cancer Models Initiative, has developed more than 50 pancreatic cancer organoids, with 40 more in development. Each organoid comes with clinical and demographic information, and the full genomic characterization of the person from whom the tumour was taken to derive the organoid. “You can pick and choose what models you’re interested in,” Walsh says. “It’s made a huge difference, because it means that researchers aren’t bogged down in trying to develop their own.”

Fancy mice

Organoids have several advantages over animal models, including that they represent the unique qualities of different people’s tumours. But mouse models still offer certain benefits. Typically, patient-derived organoids are made from tumours that have already formed, which means that all the steps leading up to that point have already happened. “The advantage in mice is you can really study progression, which gives you the opportunity to intervene before the tumour develops,” says Stanger.

One animal model that has been used extensively is known as the KPC mouse. These animals are genetically engineered to have mutations implicated in pancreatic cancer. In 2024, researchers, including Stanger, used KPC mice to test an experimental drug that targets proteins known to drive the growth of pancreatic cancer5. Positive results from that work — the drug slowed tumour growth, killed cancer cells and kept the mice alive for longer than control animals — provided preclinical validation for the drug, which is now being tested in people.

Pilarsky and his colleagues have used KPC mice to investigate the effect of blocking the gene that encodes CDK7, which helps to control how cells grow and divide6. When they blocked the gene with a drug and administered chemotherapy to the mice, the team found that pancreatic cancer cells became damaged, stopped dividing and were more likely to die.

Christian Pilarsky has developed organoids for pancreatic cancer.Credit: Shuwen Zheng

Another approach to modelling the disease in animals is to implant mice with human pancreatic cancer cells. The idea is that this should more closely mimic human disease. In 2020, Tuveson and his colleagues developed a specialized version of this model in which, rather than the usual method of transplanting a piece of fully formed human tumour, they instead delivered several pancreatic cancer organoids7. This allows the clusters of cells to grow and evolve over time, which better mimics the tumour progression seen in people. Tuveson’s team also delivered the cells directly into pancreatic ducts — which connect the organ to the duodenum — rather than just under the skin or directly into the pancreas. Pancreatic cancer usually begins in these ducts, so this enables the tumours to grow in an environment that is as similar as possible to the one in which they would naturally develop. “I think it would be a great model system,” Tuveson says of the new mice.

There are downsides to the various mouse models. Administering human pancreatic cancer cells to mice requires specialized training, potentially limiting its adoption. And because transplanting human cells into mice requires their immune system to be suppressed, studying the system’s influence on tumours is not currently possible in these models. Researchers are working on ways around this, including engineering mice to have human genes that bestow them with a human-like immune system.

For KPC mice, specifically, the constant breeding that is required to maintain a colony with two cancer-causing mutations programmed to be turned on can be a challenge. One workaround is to engineer mouse embryonic stem cells to carry the desired mutations and then use those cells to generate embryos. This way, researchers can produce mice with the genetic changes that predispose them to pancreatic cancer, reducing the number of breeding steps required.

Big data for personalized care

While animal and organoid models advance, AI is being quickly adopted by pancreatic cancer researchers. Compared with mice and organoids, AI models have the advantage of delivering real-time predictions that capture the disease’s complexity. “The AI algorithms can model highly different routes to the disease, and I, therefore, see them as complementary to more generic wet-lab models,” says Søren Brunak, a disease systems biologist at the University of Copenhagen.

AI researchers use retrospective data from thousands of individuals to train and test a model. If successful, the model can then be used to remove the guesswork and subjective interpretation about who is likely to develop cancer — and thus needs to undergo more-invasive follow-up tests. “AI does not replace my opinion, and we still have another decade at least to go before we have super intelligence in medicine,” says Azadeh Tabari, a radiologist who studies AI at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. But AI can “confirm a suspicion you have and make sure you do not lose time for your patients”.

This is because AI excels at analysing large sets of information — genetic and protein data or medical images, for example — to uncover patterns that are hard for people to spot. AI can also find subtle connections between symptoms in electronic medical records. “AI is generally good at reacting to small changes,” Brunak says. This makes it a great candidate for pancreatic cancer, for which telltale signs often show up too late.

In 2023, Brunak and his colleagues used AI to analyse the medical records of millions of people in Denmark and the United States to predict who would go on to develop pancreatic cancer8. The model identified people at high risk up to three years before their actual diagnosis. Brunak and his colleagues are now mining the text of clinical records for leads on which symptoms are linked to disease development. So far, their work suggests that heart beat abnormalities and intestinal obstructions might hold clues, although further research is needed to understand exactly how these anomalies are involved9.

Other groups are also leveraging AI to diagnose people earlier. In unpublished work, Tabari and her team used clinical data such as biopsies and imaging from 355 people with confirmed precancerous pancreatic lesions to train a deep-learning model to retroactively predict whether a lesion would become cancerous. The model achieved around 80% accuracy, suggesting that it could be used to identify at-risk individuals earlier and flag them for follow-up testing. The next step, Tabari says, is to test the model by asking it to make predictions immediately after biopsies, and then for researchers to track those individuals to see which of them go on to develop cancer.

The hardest part of the study, Tabari adds, was not building the model itself but rather finding enough high-quality data to do so. “Data curation took forever,” she says. This is a common challenge. In 2020, for example, a pilot study, supported by the US National Cancer Institute, to build a digital twin for pancreatic cancer — a computer simulation of an individual’s biology and state of disease — was stymied by the sparsity of the data that the research team were able to collect.

This resulted in “a lot of uncertainty in the model predictions”, says Matthew McCoy, a bioinformatician and computational biologist at Georgetown University in Washington, DC, who led the project. He and his colleagues have since switched their focus to breast cancer, given the better availability of data.

As high-quality data become available — and with the eventual regulatory approval of clinical protocols for use of AI systems — the hope is that the tool will provide a more holistic view of a person’s conditions, not just pancreatic cancer, Tabari says. Such an approach would combine data such as medical imaging, genetic profiling, and family and clinical history to help diagnose and predict the best treatments. “I think this is the future,” Lucchesi says.

Improvements in both modelling and therapies for pancreatic cancer will continue to go hand in hand, Tuveson says. As treatments allow people to live longer, for example, the models will need to evolve to capture the mechanisms of any emerging resistance and relapse.

Pilarsky says that he is very optimistic about the future. “With the improvement of model systems, we will be able to provide precision medicine and successfully treat a patient’s disease,” he says.