This Is for Everyone: The Unfinished Story of the World Wide Web Tim Berners-Lee Farrar, Straus and Giroux (2025)

The World Wide Web is one of those rare innovations that truly reshaped the world. It is now so deeply embedded in our daily lives that it is difficult to imagine a time before it existed or even remember how it all began. So, who better to re-examine the state of the modern Internet ecosystem, and champion reform, than the web’s creator himself: computer scientist Tim Berners-Lee? However, he is not the kind of charismatic leader who can inspire a revolution, at least not through his writing.

How AI is reshaping science and society

This Is for Everyone reads like a family newsletter: it tells you what happened, recounting the Internet’s origin and evolution in great detail, but rarely explaining why the ideal of a decentralized Internet was not realized. Berners-Lee’s central argument is that the web has strayed from its founding principles and been corrupted by profit-driven companies that seek to monetize our attention. But it’s still possible to “fix the internet”, he argues, outlining a utopian vision for how that might be done. In it, social media would be designed to “maximize the joy” the user experiences instead of fuelling division, and technical standards would be introduced to prevent the mistakes of the social-media era from being repeated in the age of artificial intelligence. Both ideas are optimistic — some might say naive — but coming from someone so integral to the web’s creation, they carry particular weight.

In this personal history of the Internet, penned with co-writer Stephen Witt, Berners-Lee recounts decades of his career at various institutions, most notably CERN — the European centre for particle physics in Geneva, Switzerland. Here, his seminal invention, the World Wide Web, began as a side project that his managers tolerated grudgingly. Much of this is a well-known tale, both because the web is so prevalent in our lives and because Berners-Lee has given plenty of interviews about how it came to be.

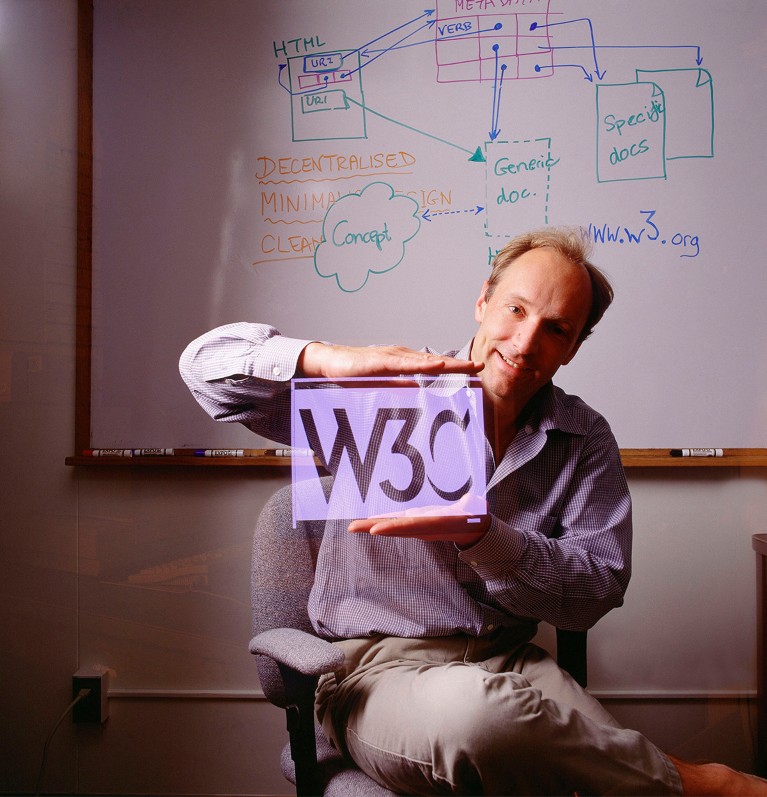

Computer scientist Tim Berners-Lee.Credit: Sam Ogden/SPL

As an author, Berners-Lee is most powerful and persuasive when he looks beyond his own life to examine the web’s exploitative corners. For instance, he notes that some US Democrats — such as senator Ed Markey and former vice-president Al Gore, who both advocated for well-thought-out technology regulations — were more willing than Republicans to engage with the web’s inner workings. He argues that this imbalance partly shaped the web’s early development in the 2000s, establishing harmful norms that still persist today.

Berners-Lee criticizes cookies — small pieces of data that websites store on users’ computers, often to track browsing behaviour — for needlessly spying on users. And he laments that the web is controlled by “a handful of providers” that “grew into dominant, unregulated monopolies”. He suggests that they ought to be brought into check.

Are the Internet and AI affecting our memory? What the science says

In the later sections of the book, Berners-Lee is refreshingly candid. He criticizes Google for attempting to dominate the World Wide Web Consortium — the non-profit organization in Cambridge, Massachusetts, that sets web standards — by embedding its preferred coding language into its Chrome browser, effectively making this language the default choice. This fight over standards is comparable to his earlier run-ins with the creators of the Mosaic browser, including entrepreneur Marc Andreessen, whose profit-driven vision for the web clashed with Berners-Lee’s original ideal of a distributed, decentralized and open system. Berners-Lee seems to have a grudging admiration for Andreessen’s success in commercializing early web browsing by ignoring the niceties of the online community that had been the norm until this point. He made changes to how browsers render images, “as was his right, I suppose”, Berners-Lee writes. Mosaic quickly became “a dominant monopoly” in the 1990s, making its rendering method the standard. Another firm Berners-Lee condemns is Apple — for steering users towards its tightly controlled app store and making it virtually impossible to download apps that are outside Apple’s ecosystem. Social-media algorithms also draw his ire; he warns that they act like “an undercover megaphone”, distorting and polluting public discourse.

His solution is as radical today as the web was in 1989. Alongside his colleagues at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, he has created a data protocol called Solid. This data-management framework gives users control over their personal information through secure ‘pods’ — individual data stores that let them decide which apps or services can access their data. This approach flips the power dynamic: sharing data with tech companies is possible, but only on the user’s terms.