Chemical oxidation of CH4

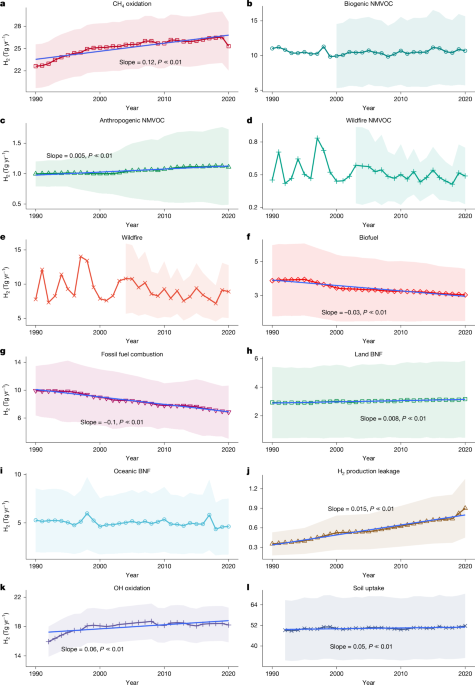

The H2 production rate from the chemical oxidation of CH4 was estimated based on its temperature-dependent reaction rates with OH (ref. 60), which produces HCHO that subsequently forms H2 through further photolysis (Supplementary Note 3). We ignored H2 produced from the CH4 + O one-dimensional reaction pathway61,62, which accounts for less than 5% of CH4 loss in the atmosphere63.

The overall fraction of H2 produced in the global CH4 reaction chain can be calculated for each time step as

$${P}_{{{\rm{CH}}}_{4}:{{\rm{H}}}_{2}}=\int {k}_{1}(T)\times [{\rm{OH}}]\times [{{\rm{CH}}}_{4}]\times {F}_{{{\rm{H}}}_{2}}$$

(1)

where k1(T) is the temperature-dependent reaction rate between CH4 and OH, \({F}_{{{\rm{H}}}_{2}}\) is the total yield factor of H2 within the whole chain, and [OH] and [CH4] are the tropospheric OH and CH4 concentrations, respectively. \({P}_{{{\rm{CH}}}_{4}:{{\rm{H}}}_{2}}\) is usually simplified by applying a global mean of [OH], k1(T), [CH4] and \({F}_{{{\rm{H}}}_{2}}\) in previous studies17,21, which can lead to large uncertainty and bias because a large variation of the global mean must be included, considering the inhomogeneous distribution of the chemical species and the reaction rates. Here, we improved the estimation by considering spatial distribution and temporal variations of H2 production from CH4 oxidation using available data from data assimilation and atmospheric chemistry model simulations. The \({P}_{{{\rm{CH}}}_{4}:{{\rm{H}}}_{2}}\) was estimated by integrating global grids with a spatial resolution at 3.75° (longitude) × 1.875°(latitude) and a temporal resolution of 3 h (3-D), which substantially reduced the uncertainty of our estimates.

The 3-D distribution of \({k}_{1}(T)\) was estimated using the temperature field from ERA-Interim reanalysis meteorology data64. We used eight [OH] fields and three [CH4] fields to produce 24-member estimates to obtain an ensemble-based mean estimate. The eight [OH] fields were obtained from the INVAST model and seven CMIP6 (refs. 65,66) models: CESM2-WACCM (ref. 67), EC-Earth3-AerChem (ref. 68), GISS-E2.1-G (ref. 69), GISS-E2.1-H (ref. 70), GISS-E2.2-G (ref. 71), MPI-ESM-1.2-HAM (ref. 72) and MRI-ESM2.0 (ref. 73). For the CMIP6 runs, we used the historical simulations that cover 1990–2014 supplemented with the SSP3-70 scenario simulation for the 2015–2020 period. The SSP3-70 scenario simulation did not consider the impact of COVID-19 on OH changes 2020, which was corrected using change ratios from INVAST. The three 3D distributions of tropospheric CH4 were produced by atmospheric transport models after surface measurement assimilation, which are CIF-LMDz (ref. 74), MIROC4-ACTM (ref. 63) and NISMON (ref. 75), respectively. The 3D \({F}_{{{\rm{H}}}_{2}}\) was computed based on the reaction chain, in which grid level values range from 0.25 to 0.7 and global mean ranges from 0.41 to 0.43 (Supplementary Note 3).

We found that our ensemble of OH fields overestimates CH4 oxidation, yielding a global mean oxidation of 517 Tg CH4 yr−1 over 2007–2018, compared with the IPCC AR6 top-down estimate of 472 Tg CH4 yr−1. Furthermore, our ensemble underestimates the uncertainty associated with OH-driven CH4 oxidation (about 8%) and H2 production (about 10%) when compared with the approximately 11% uncertainty in CH4 lifetime reported in AR6. Notably, our estimate is bottom-up, and the tendency of bottom-up models to overestimate oxidation fluxes is well-documented51, which is one reason why IPCC AR6 prioritizes top-down values for CH4 budget assessments. To reconcile these differences, we corrected the H2 production from CH4 oxidation by scaling our bottom-up H2 fluxes to match the AR6 CH4 oxidation value. Specifically, we applied a constant scaling factor of 472/519 ≈ 0.913 to the H2 production from CH4 oxidation.

To propagate the uncertainty in CH4 oxidation into the H2 production estimate, we estimated the new standard deviation (SD) as

$${{\rm{SD}}}_{{{\rm{H}}}_{2}-{\rm{production}}}^{{\prime} }={\rm{sqrt}}({\left(\frac{{{\rm{SD}}}_{{{\rm{H}}}_{2}-{\rm{production}}}}{{{\rm{SD}}}_{{{\rm{CH}}}_{4}{\rm{oxidation}}}}\right)}^{2}+{\left(\frac{{{\rm{SD}}}_{{{\rm{IPCC\; CH}}}_{4}{\rm{lifetime}}}}{{{\rm{Mean}}}_{{{\rm{IPCC\; CH}}}_{4}{\rm{liftime}}}}\right)}^{2})$$

(2)

where \({{\rm{SD}}}_{{{\rm{H}}}_{2}-{\rm{production}}}^{{\prime} }\) is the new SD for H2 production from CH4–OH oxidation, \({{\rm{SD}}}_{{{\rm{H}}}_{2}-{\rm{production}}}\) is the old SD for H2 production from CH4–OH oxidation and \({{\rm{SD}}}_{{{\rm{CH}}}_{4}{\rm{oxidation}}}\) is the SD for oxidized CH4 through reacting with OH estimated using our ensemble of OH and CH4 fields. \({{\rm{SD}}}_{{{\rm{IPCC\; CH}}}_{4}{\rm{lifetime}}}\) and \({{\rm{Mean}}}_{{{\rm{IPCC\; CH}}}_{4}{\rm{liftime}}}\) are taken from IPCC AR6, which are 1.1 years and 9.7 years, respectively.

Oxidation of NMVOC

NMVOCs are more reactive than CH4, and their chemical reaction chains to produce H2 are also more complicated and less understood. Moreover, estimates of precursor NMVOC emissions for many species are more uncertain than for CH4 because the emissions are smaller than CH4 and the sources are less clear. Owing to these uncertainties, the estimates of their contribution to the global production of H2 are more difficult and uncertain. We adopted global emission data of NMVOC from a few recently improved dataset76,77,78 (Supplementary Notes 4 and 5) to estimate H2 production from the oxidation of NMVOC.

We used the method in ref. 21, later adopted in ref. 17. Briefly, the global production rate of H2 from the oxidation of a given species of NMVOC can be approximated by

$$\underline{{P}_{{\text{NMVOC}}_{i},{{\rm{H}}}_{2}}}={S}_{i}\times \underline{{Y}_{i}}\times \underline{{F}_{{{\rm{H}}}_{2}}^{{\rm{{\prime} }}}}\times ({m}_{{{\rm{H}}}_{2}}/{m}_{{\rm{C}}})$$

(3)

where Si is the global emission rate of NMVOCi in Tg C yr−1,\(\underline{{Y}_{i}}\) is the global average yield of HCHO per carbon atom in NMVOCi. \(\underline{{F}_{{{\rm{H}}}_{2}}^{{\rm{{\prime} }}}}\) is the average fraction of HCHO that forms H2, which is 0.31 ± 0.1 (ref. 17), \({m}_{{{\rm{H}}}_{2}}/{m}_{{\rm{C}}}\) is the mass ratio between hydrogen and the carbon atom, that is, ⅙. We adopted \(\underline{{Y}_{i}}\) that is compiled based on refs. 17,21,31 (Supplementary Note 6).

The most important NMVOCs for H2 production are isoprene (C5H8), monoterpenes (C10Hx) and methanol (CH3OH), mostly from biogenic sources. We, therefore, provided an estimate of H2 production from biogenic isoprene, monoterpenes and methanol individually, and for all other minor biogenic NMVOCs collectively. We used CAMS-GLOB-BIO v.3.1, v.3.0 and v.1.2 (refs. 48,79), MEGAN_MACC (ref. 79) and MEGAN v.3.2 (ref. 80) as our main datasets to obtain global total and gridded biogenic NMVOC emissions (Supplementary Note 4).

We also consider H2 production from the oxidation of NMVOCs released from biomass burning and anthropogenic sources. The total NMVOC emission from wildfires is estimated using NMVOC emission factors computed based on species-level emission factors reported in ref. 81 and databases of grand total dry biomass burnt in different categories (Supplementary Note 5).

The total other anthropogenic NMVOC from fossil fuel combustion, biofuel combustion and other processes were acquired from three datasets. The three datasets are the widely used Emission Database for Global Atmospheric Research (EDGAR) v.8.1 (ref. 82), Community Emissions Data System (CEDS) v_2021_11_25 (ref. 77) and ECLIPSE v.6b (ref. 83) (Supplementary Note 5).

To cross-validate our estimate of total photochemical sources of H2, we also used a second method based on satellite-observed formaldehyde (HCHO) (ref. 26) to estimate total H2 production rates from photochemical oxidation (Supplementary Note 7). Both estimates show a similar increasing trend (r = 0.87) during 2005–2017, and both estimates are similar (40.5 ± 5.1 Tg yr−1 compared with 38.6 ± 1.6 Tg yr−1) during the common period 2008–2017.

Given that not all biogenic and fire NMVOC emission datasets provided data before 2000, we used a reduced number of datasets for the period 1990–2000 to ensure a complete three-decade series estimate. For biogenic NMVOC emissions, we used the single MEGAN_MACC dataset for years before 2000, but we scaled the data with a constant so its 2010–2020 mean equals the 2010–2020 ensemble mean based on all biogenic emission datasets. For fire emissions, we used the historic global biomass burning emissions for CMIP6 (BB4CMIP)84 before 2003 and again scaled it with a constant number making its 2010–2020 mean equal to the 2010–2020 mean based on the ensemble fire emission datasets.

Fossil fuel combustion

Incomplete combustion of fossil fuel produces CO, which in direct exhaust can produce H2 through the water–gas shift reaction:

$$\mathrm{CO}+{{\rm{H}}}_{2}{\rm{O}}\,\Longleftrightarrow \,{\mathrm{CO}}_{2}+{{\rm{H}}}_{2}$$

(4)

Although CO emission factors from fossil fuel combustions are known from a range of measurements, there are few measurements of H2 emission factors. However, equation (4) suggests that the production of H2 and CO are tightly coupled. Therefore, H2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion were estimated by scaling against the better-known CO emissions, using H2/CO emission ratios for different processes. We determined H2/CO emission ratios from a few sources for different sectors of fossil fuel usage (Supplementary Note 8).

The global amounts of CO emissions were obtained from the widely used and latest version of the EDGAR v.8.1 (ref. 85), the CEDS v_2024_11_25 (ref. 86) and the Greenhouse Gas–Air Pollution Interactions and Synergies (GAINS ECLIPSE v.6b) (ref. 83).

Biomass combustion

We estimated direct H2 emission from biomass combustion, including wildfires and biofuels. For wildfires, we estimated the H2 emission using emission factors reported in ref. 81 and the total amount of dry matter burnt by different combustion types from the latest version of four widely used database inventories: Fire Inventory from NCAR (FINN), Global Fire Emission Database (GFED), Quick Fire Emission Dataset (QFED) and Global Fire Assimilation System (GFAS). The uncertainty in our estimate considered both the spread among different estimates of burnt dry matter and uncertainty around emission factors (Supplementary Note 5). None of these fire datasets provided data before 2000, and some started in 2003. Therefore, we used the historic global biomass burning emissions for CMIP6 (BB4CMIP)84 before 2003 and scaled it with a constant number making its 2010–2020 mean equal to the 2010–2020 mean based on the ensemble fire emission datasets to obtain a complete time series for 1990–2020.

For biofuel, similarly as for fossil fuels, we used CO emissions from the latest version of the Emission Database for Global Atmospheric Research (EDGAR_81) (ref. 85), the Community Emissions Data System (CEDS v_2024_11_25) (ref. 86) and the Greenhouse Gas–Air Pollution Interactions and Synergies (GAINS ECLIPSE v.6b) (ref. 83). Only CEDS v_2024_11_25 has separated the emission from biofuels and fossil fuels. We, therefore, applied the same ratios of emission of CO from biofuels and fossil fuels in the same sectors from CEDS v_2024_11_25 to the other two datasets. We then used the H2 to CO emission ratios compiled from the latest literature (Supplementary Note 8) to estimate H2 emissions.

Leakage from H2 production

At present, the average global leakage rate for H2 production and distribution is relatively unconstrained. Rare measurements have been taken for the losses of gaseous H2 from its production and distribution. A previous study87 reported that losses of gaseous H2 are less than 1%, whereas those of liquid H2 are of the order of 1–10% based on a distribution grid in Germany. Another study33 used a total loss rate range of 1–4% for 2010. Because we estimate only the H2 leakage from production, we adopted a leakage rate based on several studies: (1) the Frazer–Nash Consultancy estimated an H2 leakage rate of 0.5% in the process of production88; (2) ref. 89 reported grey hydrogen production based on steam methane reforming could have a less than 1% total leakage rate; (3) ref. 90 estimated the leakage rate from blue hydrogen production to be approximately 1.5% based on a combination of natural gas leakage data and what is known about the correlation between hydrogen leakage properties and those of natural gas; (4) venting and fugitive losses often happen for natural gas production and processing; yet its leakage rate of natural gas ranges from about 0.6% (ref. 91) to about 1.45% (ref. 92). Therefore, in this study, we adopt a 1 ± 0.5% leakage rate for production.

Global production of H2 has more than tripled since 1975 (ref. 93) and will continue to rise. We take the global total demand of H2 from IEA93 (Supplementary Note 9), because the total production of H2 equals its total consumption. We linearly interpolated the total production of H2 for years not reported in IEA between 1990 and 202093.

H2 from biological nitrogen fixation

Using the direct measurement of H2 release from clover fields, a previous study34 estimated a global emission of H2 from N fixation in land at 2.4–4.9 Tg yr−1, which forms the basis for most later bottom-up estimates17,21,27,28. This source may have changed with time, for instance, because of land use and land cover changes such as cropland expansion and deforestation. To obtain a new estimate for our study period, we searched simulated outputs from models that participated in TRENDY v.10 or v.11 (ref. 94) (trends in the land carbon cycle) and obtained grid-based nitrogen fixation rates from eight TRENDY models (Supplementary Note 10). We assumed a constant ratio between H2 production and nitrogen fixation across different land cover types. We then applied the ratios of 0.032 ± 0.02, according to the nitrogen fixation rate and hydrogen production rate measured in clover fields34 and potted peanuts (Supplementary Notes 11 and 17).

Estimates of global H2 source from the oceans were carried out before by extrapolating site-measured H2 concentration to global oceans and applying the film model, which ranges from 2 Tg H2 yr−1 to 4 Tg H2 yr−1 because of different assumptions of H2 solubility in seawater17. These early estimates were lower than later estimates that are based on global oceanic N fixation rate, mainly because early measurements of H2 concentration were mainly in the North and South Atlantic and missed the Pacific, which seems to have much higher N2 fixation rates17. The recent estimate of H2 emission from N2 fixation rate assumes that the main part of H2 in oceanic water must come from nitrogen fixation by cyanobacteria. Specifically, ref. 29 estimated a global H2 emission from the oceans of 6 Tg H2 yr−1, based on a global oceanic N2 fixation rate of 150 Tg N yr−1, a stoichiometry of 1:1 for the moles of H2 produced per mole of N2 and an internal H2 loss rate of 0.45 (that is, a H2/N2 net production ratio at 0.55). We refined the oceanic source estimate of H2 by applying a similar methodology with updated global microbial N fixation data and new H2/N2 net production estimates derived from both field and laboratory incubation measurements. Based on a few contemporary estimates95,96,97,98 of global total marine fixation that is constrained by in situ measures, we adopted a total marine N fixation of 160 ± 60. To obtain a time series estimate from 1990 and a spatial estimate, we have obtained oceanic N fixation data from the NEMO-PlankTOM model and scaled the model data to make its 2010–2020 total N fixation equal to 160 Tg N yr−1. Although studies remain limited, we compiled a net H2/N2 production ratio of 0.43 ± 0.2 from a few recent studies (Supplementary Note 11).

Other minor sources

There are other minor sources of H2, which, when added together, are not negligible. One well-known source of H2 is from geological origins such as emissions from volcanoes, surface gas seeps, hot springs, mining sites, and oil and gas wells55. A previous study55 estimated the total geological origin of natural hydrogen of 23 ± 8 Tg H2 yr−1. This number is not adopted here because (1) it is too large to provide a useful constraint on our H2 budget and (2) a large part of it is deep oceanic sources (mid-oceanic rifts, oceanic crust serpentinization, the basaltic layer of oceanic crust and so on), which may hardly vent through the water surface and make it into the atmosphere. For the natural geologic origin of H2 sources, we consider only volcanic emissions. Another study99 made an early estimate of the average emission rate of 0.2 Tg H2 yr−1. Later, ref. 100 estimated 0.24 Tg H2 yr−1 for just subaerial volcanoes. Recently, ref. 101 estimated that the emission rate is 0.18–0.69 Tg H2 yr−1 for subaerial volcanoes and 0.02–0.05 Tg H2 yr−1 for mid-ocean ridge volcanoes. Combining these data sources, we estimate the emission rate of H2 from volcanoes as 0.32 ± 0.1 Tg H2 yr−1.

Fermentation processes in waterlogged soils and the digestive tracts of animals release both methane and hydrogen. Although there are many studies on the emission rate of methane, rare data and research can be found on hydrogen. A previous study102 measured an H2/CH4 emission ratio of 0.008 mol mol−1 in the flooded freshwater wetland; another study103 measured a H2/CH4 emission ratio of 0.0098 mol mol−1 and 0.005 mol mol−1 at two rice fields in Beijing and Guangzhou, China, respectively; and ref. 104 also reported an H2/CH4 ratio in a rice paddy at 0.006 mol mol−1. Using this sparse information, we adopt an average of 0.007 mol mol−1 H2/CH4 emission ratio and assume it is the same for similar systems, including paddy rice, landfills and waste treatment, and wetlands, which are estimated to have global CH4 emission as 32 [25–37] Tg CH4 yr−1, 69 [56–80] Tg CH4 yr−1 and 159 [119–203] Tg CH4 yr−1, respectively, during 2010–2020. Combining these data, we estimate a total H2 emission of 0.23 ± 0.05 Tg H2 yr−1 for these fermentation systems. Similar methods were used to estimate emissions from enteric fermentation in livestock and wild animals. There are some, but not many, measurements of H2/CH4 emission from livestock. We have collected these measurements (Supplementary Note 12) and adopted a median value of 0.022 mol mol−1, which is slightly higher than the value used in ref. 17 based on no real measurement of emission. Some wild animals have a fermentation process occurring in their rumen similar to domesticated livestock and, therefore, can produce CH4 and H2 too. Manures are found to produce H2 as well105. The same H2/CH4 ratio is assumed for ruminant emissions from other wild animals and manure management due to a lack of data. The Global Carbon Project estimated 112 [107–118] Tg CH4 yr−1 for livestock and manure management and 2 [1–3] g CH4 yr−1 for wild animals during 2010–2020 (ref. 106). Using this information, we estimate the total global H2 production from livestock production and wild animals as 0.31 ± 0.1Tg H2 yr−1.

Termites are also important H2 emitters from fermentation, as pointed out very early in ref. 107. We estimate the H2 emissions from termites also based on the reported H2/CH4 emission ratios108,109,110,111 (Supplementary Note 12). These studies measured H2/CH4 emission ratio from various termite species with varying diets, and we adopted the median value of 1.2 mol mol−1. Adopting the global CH4 emission of 10 [4–16] Tg CH4 yr−1 during 2010–2020 from the Global Methane Budget106, we estimated H2 emission from termites at 1.5 ± 0.9Tg H2 yr−1.

Human breath contains varying amounts of H2 as suggested by the clinic breath test. Assuming an average of 25 ppm H2 from human breath17 and an average breathing rate of about 11 kg air day−1 for a human being, we estimate the total release of H2 from humans as 0.048 Tg yr−1 based on an average global population of 7.37 billion during 2010–2020.

There are two other minor volume photochemical sources identified, that is, the oxidation of ozone (O3) and glyoxal (CHOCHO) (Supplementary Note 13). The yielding rate of H2 from photolysis of O3 has been measured to be 1 [0, 1.5]% (ref. 112) and 0.6 [0, 1.3]% (ref. 113). We thus adopted a median rate of 0.7 ± 0.7. A previous study114 estimated the total chemical loss of O3 at 4,360 Tg yr−1 for recent years using the latest GEOS-Chem chemical transport model combined with advanced satellite, aircraft and ground station observations. Out of this, 51% (ref. 114), that is, 2,180 Tg, is lost through the photolysis path (Supplementary Note 13) that produces H2. Using these data, we directly estimate the global production of H2 from O3 oxidation as 0.64 ± 0.64 Tg H2 yr−1. Glyoxal is mainly formed in the oxidation of VOC, similar to the production of HCHO through VOC oxidation. The global source of glyoxal is about 48 ± 8 Tg yr−1 (refs. 115,116,117). Also, the yielding rate of H2 of glyoxal oxidation (equation (R3b) in Supplementary Note 13) equals that of HCHO oxidation (equation (R3) in Supplementary Note 3). Adopting the yielding rate of the HCHO process of H2 production at 0.65 ± 0.15×0.6 ± 0.1 (ref. 17), we estimate an H2 production of 0.65 ± 0.2 Tg H2 yr−1.

Reaction with OH

H2 can be removed from the atmosphere by reaction with OH:

$${\text{H}}_{2}+\text{OH}\to {\text{H}}_{2}{\rm{O}}+{\rm{H}}$$

(5)

The global loss of H2 by this reaction can be estimated by integration over a 3D space:

$${L}_{{{\rm{H}}}_{2}\text{:}{\rm{OH}}}=\int {k}_{5}(T)\times [{\rm{OH}}]\times [{{\rm{H}}}_{2}]$$

(6)

where, the temperature-dependent reaction rate (k5(T) = 2.8 × 10−12 × exp(−1,800/T) mol−1 cm3 s−1) is estimated using the ERA-Interim reanalysis meteorology data64, and the [OH] is taken from model-simulated 3D [OH] fields, as mentioned earlier. We used our 3D distribution of H2 produced through kriging interpolation (Supplementary Note 1). The same scaling and uncertainty propagation approach used for estimating H2 production from CH4 oxidation was also applied here to scale H2 loss from its reaction with OH and adjust the corresponding uncertainties.

Soil uptake

There is plenty of evidence for uptake of H2 in soils containing organic carbon from observations in both the laboratory and the field41,118. A mini review of previous studies of soil H2 uptake was provided in Supplementary Note 14.

We adopted the process-based model developed in ref. 41 as the main model to estimate the monthly deposition rates from 1992 to 2020. Details of this model can be found in ref. 41.

To also account for the uncertainty in estimating soil properties that influence hydrogen uptake velocities, soil data of the top layer (about 10 cm depth) were obtained from simulations of a group of dynamic global vegetation models. These models include eight models that participated in TRENDY v.10 project94, as contributions to the Global Carbon Budget 2021 (ref. 119) and another two models—SPLASH (simple process-led algorithms for simulating habitats)120 and the global land data assimilation system (GLDAS) reanalysis data. The eight TRENDY dynamic global vegetation models are LPX-BERN, JULES, ORCHIDEE, CABLE-POP, VISIT, JSBACH, CLASSIC and CLM5.0, which account for various soil characteristics to simulate land–atmosphere flux. We used both the input soil parameters, including the clay fraction of soil, sand fraction of soil and total soil porosity of these models, as well as simulated monthly soil temperature, soil moisture and snow depths. An exception is SPLASH because the current version could not properly simulate soil temperature, and we used GLDAS soil temperature instead.

To account for uncertainties arising from different parameterizations, we considered another six additional parameterizations (Supplementary Note 15). These include (1) adopting the diffusion scheme used in refs. 19,22,121; (2) adding the effect of dry top layers acting as a diffusion barrier, following ref. 122; (3) instead of using net productivity or Normalized Difference Vegetation Index to constrain H2 deposition velocities, adapting the scheme from ref. 22 that using soil carbon content to constrain; (4) adopting the scheme of soil moisture content regulation from ref. 122; (5) Changing the maximum biological uptake (kmax) to a low bound value (0.01226 s−1) based on measurement in ref. 123 and a high value (0.1 s−1) derived from ref. 122. A previous study124 developed a new parameterization on soil moisture regulation of kmax, using a function on soil water potential with an activation threshold at the wilting point. We did not include it because the required values for soil-type-specific coefficients provided in ref. 124 shall not be directly used for TENDY soil products, as their soil texture or types may be different from those used in that paper to derive those values. With an ensemble of 10 models for simulating soil properties, this parameterization is difficult to apply because the coefficient values must be re-derived for different soil types across different models.

In summary, we estimated an ensemble of monthly H2 deposition velocities using 10 sets of soil inputs and seven model parameterizations for modelling H2 deposition velocities, resulting in a total of 70 model runs. Applying the observed H2 mixing ratio in the atmosphere (Supplementary Note 1) to these deposition velocities, we then estimated an ensemble H2 uptake rate by soil.

Hydrogen climate impact

Increasing atmospheric H2 leads to indirect climate impacts, and its future concentration and climate impact will depend on how both sources and sinks change over time.

To estimate the climate impact of changing H2 concentrations in the future H2 economy, we used v.4.0-alpha-1 of the compact Earth system model OSCAR to simulate the CH4–H2 system. We updated the published OSCAR v.3.3 (ref. 125) with three key changes: updated tropospheric and stratospheric lifetimes of all non-CO2 greenhouse gases, updated radiative forcing of short-lived species (aerosols and ozone) and the inclusion of the H2 biogeochemical cycle. The integration of H2 biogeochemical cycle into OSCAR covers two aspects: the representation of the H2 cycle and budget, and the integration of its impact on tropospheric OH lifetimes (which feed back on species affected by OH such as CH4) and on the effective radiative forcing of ozone and stratospheric water vapour (direct impact of H2 and indirect impact through changes in CH4). The detailed description of the model is provided in Supplementary Note 16.

To isolate the contribution of H2 to climate change and avoid too many interactions in the Earth system, we isolate the CH4 and H2 cycles and their interactions by prescribing the atmospheric concentrations of all other greenhouse gases (CO2, N2O and 48 halogenated compounds) to the model. We also prescribed the effective radiative forcings from forcers that are not directly related to the CH4–H2 system in the model (all aerosols, aviation-induced cloudiness, light-absorbing particles on snow, albedo from land use change, stratospheric volcanic aerosols and solar activity). The resulting system describes the evolution of atmospheric CH4, atmospheric H2, stratospheric water vapour and tropospheric and stratospheric O3, as well as the global climate change induced by these forcers and the prescribed ones. Apart from the atmospheric concentrations and effective radiative forcings listed above, the resulting model is driven by time series of anthropogenic and biomass burning emissions of H2, CH4, NOx, CO and VOCs.

Using time series forcing data (Supplementary Note 16), we simulated past and future changes in the CH4–H2 system to estimate the climate impact of hydrogen. Several sets of preliminary simulations, including both concentration-driven and climate-driven scenarios, were conducted over the historical period to assess the ability of the model to reproduce the evaluated budget and to estimate any budget imbalance through mass conservation. These were performed before the main simulation. The main simulation is emission-driven for both the historical and future periods, in which we incorporated previously diagnosed missing fluxes from unrepresented processes to accurately reproduce reconstructed historical atmospheric concentrations. This main simulation was then compared with a counterfactual scenario in which atmospheric H2 levels were fixed at preindustrial values, allowing us to quantify the climate impact of the lack of representation of H2 in climate projections.

The H2-cycling-related input data for historical and future simulations are either based on or constrained by our budget (Supplementary Note 16). For future simulations, we consider only a few typical warming scenarios, that is, different marker SSP scenarios (SSP5-85, SSP4-60, SSP4-34, SSP2-45, SSP1-26 and SSP1-19; SSP3 is excluded as no hydrogen-related variable was reported). The scenarios provide projections of the concentrations and emissions of CH4, NOx, CO, VOCs and other gases needed for our climate model, as well as the total usage of H2. To estimate projected H2 concentrations in these SSP scenarios, H2 emissions excluding leakage are derived from precursor emissions (for example, CO, CH4 and NMVOCs) in the same way as for the historical period and scaled to match our 2020 estimates. The H2 leakage was estimated by combining future H2 usage data from the IPCC AR6 database and possible hydrogen leakage rates.

As more hydrogen is used in the economy, the production methods and uses of hydrogen will evolve, altering the extent and likelihood of hydrogen leakage. Future consumption of hydrogen is likely to be more distributed, for instance, in vehicles or blended into pipeline gas, and will no longer be mostly co-located with the production sites. Hydrogen end uses will be more diverse, involving sections such as blending with natural gas, iron and steel, electricity generation, road transport, chemical synthetic fuels, refineries, shipping and aviation, and buildings. Furthermore, the production technology of H2 is also likely to evolve, with more hydrogen being green hydrogen instead of grey and blue hydrogen. All these factors will contribute to varying leakage rates in the future and H2 is generally considered more prone to leakage than CH4 because of its smaller molecule size unless specific mitigation measures are implemented. However, as mentioned above, there is still limited empirical data available to constrain the estimate of future leakage rates. Reported leakage rates across different components of the hydrogen value chain vary substantially—from as low as 0.0001% to as high as 20% (refs. 126,127). However, the average economy-wide leakage rates are expected to be less extreme10,127. Following the most recent studies on assessing the climate benefits of H2 (refs. 3,11,50,128), we adopted an economy-wide hydrogen leakage range of 1–10%.

Uncertainties and limitations

Our analysis and synthesis of H2 fluxes are based on a range of bottom-up inventories and models, subject to various uncertainties and limitations. First, many process-based models are used, including those for modelling H2 directly (for example, the soil uptake model), for modelling input data to the H2 model (for example, the TRENDY models) and for modelling precursor species and activities (for example, the models for estimating NMVOC emissions and the NEMO-PlankTOM ocean model for estimating BNF). These models include uncertainty associated with differences in model configuration as well as process parameterization, although the same forcings are applied to the same group of models to reduce variation among models (for example, TRENDY models). Second, inventories of precursor gases (for example, CH4 and CO) include uncertainties originating from the underlying statistical activity data and emission factors they are based on refs. 77,129, regardless of the tiered approach used. These uncertainties contribute to our estimate of H2 flux. For instance, waste management and solid biomass combustion are hard to track, partially because of informal and small-scale consumption or applications, leading to high uncertainty in the estimate of CH4 and CO emissions and, therefore, related H2 emissions. Last, there are limitations associated with the H2 emission and yield factors because of limited measurement and variation among sources and regions. We used global and time constant H2 yield factors from NMVOC and emission factors for transportation. However, these factors could vary across space and time because of different atmospheric or technological conditions, among NMVOC species, and among different types of vehicles. As more empirical data become available, a more detailed and comprehensive treatment of these emission and yield factors shall be needed to improve the estimate. Although we did not optimize any sink/source terms as in top-down inversion studies, top-down estimates were still used for constraining some terms. One maximal biological uptake value (that is, 0.038 s−1) was tuned to match the global mean soil update from a top-down estimate41, whereas two others were derived from an experiment or a soil moisture parameterization scheme to reduce this dependence. Our 3D CH4 concentrations were obtained from top-down inversions, and our CH4 and OH oxidation terms were calibrated to match top-down CH4 oxidation estimates. This dependence could be alleviated in the future through reliable measurements of the maximal biological uptake rate and the development of more consistent, better constrained OH fields.

In this study, we try to track and quantify the propagated uncertainties as much as possible, but we acknowledge that we could not include all sources of uncertainty. We collect as much activity data as possible, precursor gas emission data and emission factors. Our estimate of H2 sink/sources was then based on the mean value of these ensemble collections, and the ensemble standard deviation was used to represent the uncertainty of the estimate. The uncertainty estimate in terms of standard deviation in our analysis includes all levels of uncertainties: (1) uncertainty of each single data source of activity or precursor gas emission if it is available; (2) variation among different data sources for each activity type or precursor gas species; (3) variation among emission factors for both precursor gas and H2 when a collection of measurements is available; (4) different model input data and parameterization in case of process modelling (that is, the soil H2 uptake modelling). When adding terms (that is, different inventories of gas emissions), the resulting standard deviation is computed as the square root of the sum of variances of all terms, assuming each term is normally distributed and independent. When multiplying terms, Monte Carlo simulations are applied in R language to compute the final standard deviation.