Students in a biology laboratory around 1899 at the North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, a historically Black university in Greensboro. Credit: Buyenlarge/Getty

Throughout the twentieth century and beyond, the record of colleges and universities set up to provide higher-education opportunities for Black students in the United States could be viewed as one of failure. Their mission was to produce scholars to create economic, social and political freedom for African Americans. But, in the nearly 200 years since the first historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) opened their doors, Black people in the country still have not achieved economic parity with white people.

Springboard to science: the institutions that shaped Black researchers’ careers

Yet this failure cannot be laid at the feet of the Black universities’ leadership. No strategy that they could have deployed would have made a difference. The suppression of African American achievement was intentional and systematic. It occurred because many of those who controlled white society (particularly in the former Confederate states) never wanted African Americans or their institutions to achieve social equality1 — and I argue that this is not a priority for the second administration of US President Donald Trump either. This does not mean that all white people are racists: indeed, many have taken an active role in the fight against structural racism. However, the majority have either bought into or been unwilling to take action against a social and political system that has and continues to deny opportunity to African Americans2.

For most of the twentieth century, the majority of this group accepted the inferiority of people of African descent as socially agreed ‘fact’. This allowed powerful institutions to discriminate against African Americans. For example, redlining, which occurred between 1934 and 1968, became a widespread practice in the United States to deny loans and housing to African Americans, and it led to different capacities for accumulating wealth. Today, owing in large part to such policies, the median wealth of white families is about 6.5 times greater than that of African American families3.

Historic inequality in Black education

I have reviewed the history of African American higher education in the context of evolutionary science4, but the essential details of the story are the same across scientific disciplines. The second Morrill Land-Grant Act, enacted in 1890, established 19 HBCUs in the US South to provide opportunities for Black students. But these institutions and the 1862 Morrill Land-Grant Act institutions, which educated white students, were never funded equitably (see ‘HBCUs: a history of underfunding’).

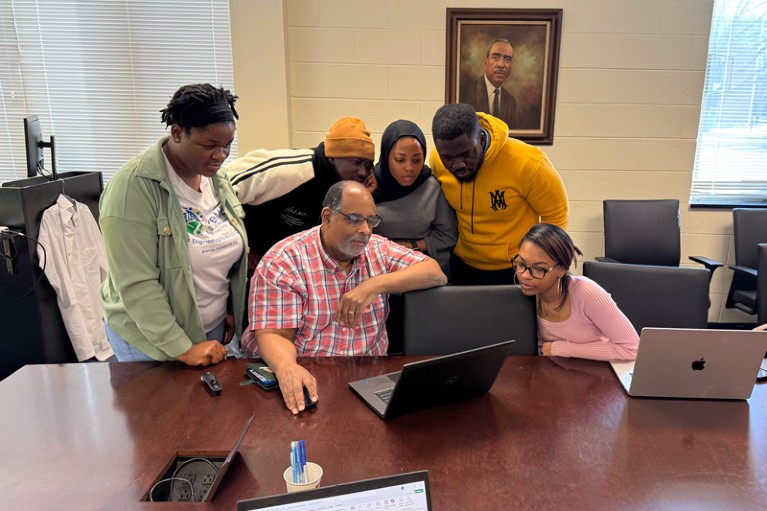

Joseph L. Graves Jr shows students in his evolutionary-medicine class how to construct spreadsheets to analyse models of natural selection.

Compared with their historically white institution (HWI) counterparts, HBCUs admit a disproportionate share of students from struggling school districts, a result of historical inequalities in primary and secondary education in the country. Yet, state appropriations to HWIs are larger than those to HBCUs in the US South. For example, in 2021–22 the state budget appropriation per undergraduate student at the North Carolina State University (NCSU), an HWI in Raleigh, was $35,513 per student, but at my institution, the North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University (NCATSU) in Greensboro, an HBCU, it was $19,083. This means that for every dollar spent on a student at the NCATSU, $1.86 is spent on a student at the NCSU.

This situation is common across the US Southeast, as documented in a 2023 report on the status of HBCUs5 from the Century Foundation, a think tank in New York City. Between 1987 and 2020, Florida, Louisiana, North Carolina, Tennessee and Texas underfunded their HBCUs by $8.5 billion compared with their HWIs, according to letters to the governors of these states, sent in September 2023 by Miguel Cardona, secretary of education and Thomas Vilsack, secretary of agriculture. The NCSU and the NCATSU have a $2-billion funding disparity, one letter said. The federal government has never forced states to fund white and Black higher education equitably, and it has never denied funds to states that continue discriminatory funding practices.

Biden must keep funding pledge to historically Black colleges and universities

This historical underfunding has produced an environment in which HCBU faculty members have to shoulder disproportionately heavy teaching loads, advise more students — many of whom are underprepared — and operate in facilities that are ill-suited for twenty-first century instruction and research in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). HBCUs operate on shoestring budgets, so they have fewer resources for research, teaching and student and community programmes. Owing to budgetary shortfalls, administrators at HBCUs often have to delay purchasing or repairing much-needed technology and infrastructure. For example, in January 2024, the central heating plant at the NCATSU failed, so the institution had to house students in hotels or send them home.