The number of cells of a given type in a tissue section can change by division or death, moving in or out of the section (flux) or transdifferentiation40. If we restrict ourselves to modelling cell types that do not transdifferentiate at appreciable rates, such as T cells and macrophages, and analyse tissues in which flux is negligible relative to rates of death or division (or where we can add flux terms post hoc), we remain with the following equation for the rate of change of a population of cells of type \(i\):

$$\frac{d{X}_{i}}{{dt}}=\frac{{\rm{\#}}\mathrm{Divisions}}{{dt}}-\frac{{\rm{\#}}\mathrm{Deaths}}{{dt}}$$

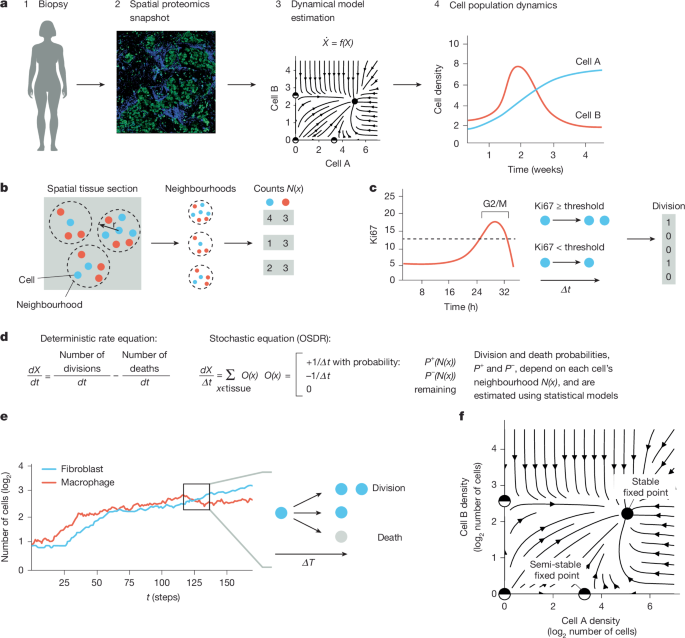

OSDR aims to transition from static observations of cell division or death in a tissue into rates. The key insight is: if we obtain a marker for cell division (or death), and in each cell division the marker remains above a defined threshold for a time period \({dt}\), then all observed divisions occurred within the last \({dt}\) hours. Thus:

$$\frac{d{X}_{i}}{{dt}}=\frac{{\rm{\#}}\mathrm{Divisions}}{\mathrm{Time}\,{\rm{a}}\,\mathrm{division}\,\mathrm{remains}\,\mathrm{observable}}-\frac{{\rm{\#}}\mathrm{Deaths}}{\mathrm{Time}\,{\rm{a}}\,\mathrm{death}\,\mathrm{remains}\,\mathrm{observable}}$$

The rate of division or death of a cell is influenced by the signals that it receives from its environment, its access to nutrients, its genetics and factors such as physical contact with other cells. We call this complete set of factors the ‘neighbourhood’ of the cell. This definition sets an ideal, and we denote the particular set of features used to approximate this ideal as \(N(x)\), where \(x\) is some cell in the tissue.

If we consider cells with identical neighbourhoods, a fraction of them will be dividing. This fraction is higher if the neighbourhood induces a high rate of division. We thus viewed the observations of division or death as random events whose probabilities are determined by the neighbourhood of the cell. Thus, for cell \(x\) of type \(i\), the distribution of the observation \({O}_{i,t}(x)\) of a division or death event is modelled as:

$${O}_{i,t}(x)=\left\{\begin{array}{cc}+1/d{t}^{+} & \text{with probability}\,{p}_{i}^{+1}(N(x))\\ -1/d{t}^{-} & \text{with probability}\,{p}_{i}^{-1}(N(x))\\ 0 & \text{remaining}\end{array}\right..$$

Where pi+1 and pi−1 are the statistical inference models for division or death, and dt+ and dt− are the durations of observed division or death markers, respectively. In this study, dt+ is defined as 1 time unit (roughly a few hours; ref. 27), and the approximation of the death rate as the mean division rate is defined using the same time units. Thus, in this implementation dt+ = dt− = 1. We divided by the durations so that the (stochastic) change in the number of cells in each timestep is:

$$\frac{d{X}_{i}}{{dt}}=\sum _{x\in {X}_{i}}{O}_{i,t}(x)$$

Tissues are heterogenous, and the diverse cellular compositions in different regions result in various directions of change. To analyse the change at a certain state, rather than the change in complete tissues, we computed the expected change with respect to an initial condition where cells share the same neighbourhood:

$${E}_{x}\left[\frac{d{X}_{i}}{{dt}}\right]\,=\,E\,\left[\sum _{x\in {X}_{i}}{O}_{i,t}(x)\right]\,=\,{\rm{\#}}{X}_{i}\,[{{p}_{i}}^{+1}(N(x))-{{p}_{i}}^{-1}(N(x))]$$

In this study, features are based on the number of neighbouring cells of each type within a predefined radius. For further discussion on this choice of features, see Supplementary Fig. 2f. The neighbourhoods can thus be represented as a vector of cell densities:

$$X:= {({X}_{1},{X}_{2},\ldots ,{X}_{k})}^{T}$$

As a result, we can interpret the inferred statistical models as components of a set of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) defined over a state-space of cell densities:

$$\frac{\text{d}}{\text{d}t}X=\left(\begin{array}{c}{X}_{1}\,({p}_{1}^{+1}(X)-{p}_{1}^{-1}(X))\\ {X}_{2}\,({p}_{2}^{+1}(X)-{p}_{2}^{-1}(X))\\ \vdots \\ {X}_{k}\,({p}_{k}^{+1}(X)-{p}_{k}^{-1}(X))\end{array}\right)=f(X)$$

Note that OSDR is inference-model agnostic; although we used logistic regression here, other statistical inference models can be adopted within this framework. In addition, this approach can be applied to data acquired by any technology that enables classification and spatial localization of discrete cells, together with reliable measurement of markers for division (and possibly death).

Model inference algorithm

For input:

Cell-level annotations: \(({B}_{i},{T}_{i},{\vec{x}}_{i}{,O}_{i})\) for cell \(i=1,\ldots \,N\)

-

\({B}_{i}\) denotes an ID for the biopsy sample cell \(i\) came from. \({B}_{i}\) is used to formalize that a cell can only influence cells from the same tissue.

-

\({T}_{i}\in T\) indicates the cell type for cell \(i\) (for example, \({T}_{i}\,=\) ‘fibroblast’), and let \(T\) be the set of types.

-

For any \(t\in T\), let \({n}_{t}\) be the total number of cells of type \(t\). We also assumed some order on the cells of type \(t\), such that: \(t[\,j]=i\) for any index \(j\in \{1,\ldots {n}_{t}\}\), and the original index \(i\in \{1,\ldots ,N\}\).

-

\(\vec{{x}_{i}}\in {R}^{2}\) denotes the 2D spatial coordinates for cell \(i\).

-

Oi ∈ {0,1} refers to the binary observation of division.

For the algorithm:

For each cell type \(t\in T\):

-

(1)

Compute a table of features (neighbour counts of each cell type) \({X}_{t}\in {R}^{{n}_{t}\times T}\).

$${X}_{t}[i,{t}^{{\prime} }]:= \mathop{\sum }\limits_{j=1}^{N}1\,[{B}_{j}={B}_{t[i]},{T}_{j}={t}^{{\prime} },\Vert {\overrightarrow{x}}_{t[i]}-\overrightarrow{{x}_{j}}\Vert < r]$$

Here \(t[i]\) is the original index of the i-th cell of type \(t\). The value at row \(i\) and column \(t{\prime} \) is a count of all cells that came from the same tissue as cell \(t[i]\), that have type \(t{\prime} \) and are within a distance \(r\).

Row \(i\) in \({X}_{t}\) is our representation for the neighbourhood of the cell \(t[i]\): the counts of all cell types in its proximity. Denote this vector by \(N(t[i]):= {X}_{{T}_{i}}[i,:]\).

-

(2)

Perform feature transformations on \({X}_{t}\), such as adding interaction terms (transformations are selected through a separate process of cross validation).

-

(3)

Define the binary cell-division labels \({y}_{t}\in \{\mathrm{0,\; 1}{\}}^{{n}_{t}}\):

$${y}_{t}[i]={O}_{t[i]}$$

-

(4)

Fit a multivariate logistic regression model \({p}_{t}^{+}\) for the division rate based on the features and labels \({X}_{t},{y}_{t}\).

-

(5)

Define the death rate:

$${p}_{t}^{-}={\mathrm{mean}(y}_{t})$$

For output:

$$(({p}_{t}^{+},\,{p}_{t}^{-}):t\in T)$$

Ki67 thresholds

We used previous data to establish a Ki67 threshold for cell division events. Uxa et al.27 have demonstrated that Ki67 levels peak towards the G2/M phase of the cell cycle, with preserved kinetics (up to scale) across two human and one mouse cell line. We adjusted Ki67 levels to correct for different scaling and division rates between cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 1a,b) by selecting Ki67 values above a noise threshold \({T}_{n}\), subtracting \({T}_{n}\) and dividing by the Ki67 standard deviation. We choose \({T}_{n}=0.5\) mean isotopic counts because this is the typical magnitude of experimental noise in this dataset (Supplementary Fig. 1c). This produces distributions with similar shape (Supplementary Fig. 1d) in accordance with the cell line results from Uxa et al. We defined a cell division by the normalized Ki67 above a division threshold \({T}_{d}\). Example fractions of dividing cells are provided in Supplementary Fig. 1e. The resulting model estimates are robust to \({T}_{d}\) values between 0 and 1 on this adjusted scale (Supplementary Figs. 3f and 4g).

Choice of spatial proteomics technology

Out of the currently available spatial-omics technologies, multiplexed protein imaging41,42,43,44 was the most suitable for our setting. Current barcode-based spatial transcriptomics45,46 aggregate cells in spots of 55 µm in diameter so that they do not associate transcript levels with single discrete cells. In addition, because the distance between spot centres is 100 µm, if we place a cell in the centre of a spot, we measure less than one-ninth of the area immediately surrounding it (area of a circle of radius 27.5 µm, within another of radius 72.5). Fluorescent-based approaches such as MERFISH allow modelling single cells but they only recover a small fraction of every transcript in the tissue. This is a barrier for basing the analysis on levels of a single transcript: Ki67. IMC provides measurements within well-defined cells, reliable measurement of Ki67 and, in terms of cost, makes datasets in the order of magnitude of hundreds of thousands of cells feasible. Classical staining methods should also be feasible for analysing specific pairs of cells. For example, for analysing fibroblasts and macrophages, we could use four markers: fibroblast and macrophage markers, a cell nucleus marker and Ki67.

Implementing OSDR using spatial transcriptomics would allow more fine-grained definition of cell types based on transcriptional profiles. Cell division and death events could be defined based on multiple gene expression markers, rather than Ki67 used here, enhancing the accuracy of the method. In principle, OSDR can compute dynamics of many cell types and subtypes, beyond the six studied here. We expect the required number of cells to increase with the number of cell subtypes considered. Future work can add computation of transitions between cell subtypes or states to more fully capture cell population dynamics.

Data exclusion

We excluded outlier samples that deviated by more than six standard deviations in both cell density and number of cell divisions. These excluded outliers amounted to 3 samples out of 718 in the Danenberg dataset2, and 2 samples out of 771 in the Fischer dataset4.

Enforcing maximal density

We assumed there cannot be a net positive flux at the maximal observed density of a cell type. We applied a correction in the form of:

$${{p}_{i}}^{\mathrm{correction}}={c}_{i}\cdot {{d}_{i}}^{n}$$

Where di is the density of cell I, and the power n controls the steepness: high n implies that the correction applies primarily to higher densities (Supplementary Fig. 1f,g). The constant term ci is defined as the minimal correction ensuring non-positive flux at maximum density (Di). We compute division minus death rates at the maximal density of one cell, over all possible values of the second cell:

$${c}_{i}\cdot {{D}^{n}}_{i}=\mathop{\max }\limits_{N(x):{d}_{i}={D}_{i}}{{p}^{+}}_{i}(N(x))-{{p}^{-}}_{i}(N(x))$$

In practice, the state-space region near maximal density for both cell types is unpopulated by cells, so we used values up to the 95% quantile density for each type. This is more robust to extrapolation errors in areas with minimal data. For the fibroblast–macrophage model, this correction is trivial because the estimated net flux is negative at high densities; for the T and B cell model, the correction makes a difference only to T cells (Supplementary Fig. 1g).

Population versus neighbourhood dynamics

In OSDR, we first estimated the cell-level models for division and death probabilities (see ‘Model inference algorithm’ in Methods). We then used the cell-level models to analyse tissue dynamics in one of two ways.

We called the first approach ‘population-level dynamics’. We started with a spatial tissue section. We then produced a temporal sequence of tissue snapshots as follows. We first computed the probabilities of division and death for each cell, taking into account the composition of the neighbourhood of each cell. We then used the probabilities to sample for each cell: division, death or none. We placed each new cell in the neighbourhood of the dividing cell. We removed cells that died (Supplementary Fig. 1h).

One nuance in this process relates to cells at the edge of the tissue. When a cell near the edge of the tissue divides, its daughter cell might be placed outside the tissue. To keep tissue size fixed, we removed cells placed out of bounds. This biases the neighbourhoods of cells near the edge of the tissue. To correct this bias, we rescaled the cell counts of cells near the edge of the tissue: \(\mathrm{Number}\,\mathrm{of}\,\mathrm{cells}\,\mathrm{in}\,\mathrm{neighbourhood}\cdot \frac{1}{\mathrm{Neighbourhood}\,\mathrm{fraction}\,\mathrm{within}\,\mathrm{tissue}}\). This is an unbiased estimator of neighbourhood composition, as the ‘neighbourhood fraction within the tissue’ is also the probability of keeping a daughter cell following division.

We can also add cell movement to this sampling procedure. We implemented a random walk by sampling a Gaussian translation to each cell at each time step. Note that a large diffusion coefficient can disperse cells out of tissue boundaries (Supplementary Fig. 1i), whereas a small diffusion coefficient can cause regions in the tissue to be effectively isolated (Supplementary Fig. 1j). More elaborate modes of cell movement include attraction towards a chemokine source, adhesion to nearby cells and migration of cells from outside the tissue. Studying the effects of different modes remains outside the present scope.

To study a sequence of tissue sections, we plotted the number of cells over time (for example, Fig. 4e,f). Because tissues can have different sizes, we found it useful to rescale the number of cells to the area of a neighbourhood. Thus, the y axis displays: \(\mathrm{Number}\,\mathrm{of}\,\mathrm{cells}\,\mathrm{in}\,\mathrm{tissue}\cdot \frac{\mathrm{Neighbourhood}\,\mathrm{area}}{\mathrm{Tissue}\,\mathrm{area}}\).

One limitation of plotting the average density is that we do not observe the complete distribution. Of note, the average density does not necessarily coincide with the mode. Supplementary Fig. 1k shows a simulation in which the mode locates the stable fixed point of the system, rather than average density.

Thus, to analyse population dynamics, we needed to specify an initial spatial tissue configuration and a diffusion coefficient. We had to also consider the distribution of neighbourhood densities across the tissue. The second approach for analysing tissue dynamics did not require these choices.

We called the second approach ‘neighbourhood-level dynamics’. Here we analysed an ODE obtained by computing the average direction of change of each cell type (Methods). To analyse this ODE, it was convenient to plot phase portraits for 2D models (for example, Figs. 2b–d, 3f and 4c) and trajectories for higher dimensions (for example, Fig. 5b).

Generally, population and neighbourhood dynamics do not have to agree. The population model is stochastic and discrete, whereas the neighbourhood model is deterministic and smooth. We constructed examples to highlight two important differences between the population and neighbourhood approaches.

The first type of discrepancy results from collapse of a cell population. In the deterministic neighbourhood dynamics, a cell population will always flow in the average direction of change. Thus, if a cell population has a positive stable fixed point, it will deterministically flow towards it. Conversely, in the stochastic population dynamics, a cell population can move against the average direction of change. If due to a random fluctuation, all cells in a population die, the population will not recover. This can produce large differences between neighbourhood and population dynamics. A collapse is more likely to occur for cells with a low-density fixed point. It is also more likely without diffusion. Adding even small diffusion allows neighbourhoods with higher densities to ‘rescue’ neighbourhoods that had collapsed. Supplementary Fig. 1l shows that the macrophage population eventually collapses without diffusion. Adding diffusion produces similar steady states under both models (Supplementary Fig. 1l).

A second type of discrepancy results from the initial tissue configuration. Population dynamics depend on the initial tissue configuration, whereas neighbourhood dynamics do not. Certain particularly ‘adversarial’ tissue configurations, coupled with low cell motion, can produce large discrepancies. For example, under neighbourhood dynamics, the T and B cell model produces a flare from a location of (4,1) on the TB phase portrait (Fig. 4c). Under population dynamics, a flare also occurs when we initialize a tissue by placing cells at random (Supplementary Fig. 1m, first example). However, we could organize the same number of cells such that no flare occurred. For example, we can place T cells at one side of the tissue and B cells at the other. In this case, the B cell population collapses because the B cells do not have T cell neighbours (Supplementary Fig. 1m, second example). Another option is placing all B cells in the same place, creating a high density of B cells locally. In this case, the low density of B cells at the tissue level does not reflect their high density locally (Supplementary Fig. 1m, third example). In these examples, we used our understanding of neighbourhood dynamics to design a tissue configuration that produces a discrepancy.

Simulations of known dynamical models

To determine the accuracy of the inferred dynamical model as a function of sample size, we simulated spatial data based on a known dynamical model (that is, predefined functions p+ and p−) using the following procedure:

-

(1)

Sample a random initial number of cells for each cell type.

-

(2)

Sample a random spatial position in the tissue for each cell.

-

(3)

For n steps:

-

(i)

Compute for each cell the probability of division or death based on its current neighbourhood.

-

(ii)

Sample an event of division, death or none based on the computed probabilities.

-

(iii)

Remove dead cells and place a new cell next to each dividing cell (here the location of new cells is sampled uniformly within the neighbourhood. It is straightforward to incorporate knowledge about cell motility at this stage, if available).

-

(i)

This produces a tissue section whose density and spatial distribution is produced by the dynamics, as we assume is the case for real tissues. We repeated the procedure 100 times from various initial densities and sample with replacement 50,000 cells evenly from all tissues. From this pool, we then sampled 1,000, 5,000, 10,000 or 25,000 cells for the model fits.

Because empirical distributions in our data had tails towards lower cell densities, we sampled the initial cell densities from a β-distribution biased towards lower densities (parameters 2,4 scaled to a maximal value of 7). Model parameters were selected to produce division rates in ranges that resemble real data (mostly within 1–6%). The fraction of divisions was approximately 2% for all models. We selected the number of simulation time steps as that required to produce distributions qualitatively similar to real data.

To evaluate model fits, we tested whether the correct location and type of stable or semi-stable fixed points were recovered (Supplementary Fig. 2g–k), as well as accuracy of reconstructed basins of attraction (Supplementary Fig. 2l–o). To account for discretization error, if a stable point on an axis was recovered, and an unstable point was located within less than one cell from that point, we considered it as semi-stable. Such a point has effectively no basin of attraction. The same precaution should apply to interpretation of model fits in general.

For a detailed analysis of the simulations of each ground truth model, see Supplementary Fig. 2g–o.

Plotting Ki67 levels as a function of neighbourhood composition

Figures 3d,e and 4a,b display the measured Ki67 > threshold as a function of neighbourhood composition. To transform the cell-level binary division events into rates, we computed a local average and subtracted the mean division rate. For the local average, we used a Gaussian smoothing kernel over the cell-density state-space, providing a non-parametric plot of the division rate. The gamma parameter of the kernel controls the degree of smoothing. We plotted a value of gamma that produces contours of similar complexity as those of the estimated parametric models.

Magnitude of error due to unmodelled terms

To estimate the effect of unmodelled processes we applied a Fokker–Planck approach. Each tissue is analogous to a particle moving through a space whose coordinates are defined by the densities of each cell type. For example, the location \(x\) could be the density of fibroblasts and macrophages (that is, \(x=(F,M)\)). The velocity through this space is determined by the rate of change in each cell type. This velocity has a deterministic component composed of \(\vec{v}(x,y)\), the division minus removal rates that we previously estimated using division markers, and \(\vec{u}(x,y)\), which includes unmodelled terms such as cell migration and differentiation from stem cells. The velocity also includes a stochastic component, which reflects fluctuations in velocity of each cell type.

Applying the Fokker–Planck equation to our setting:

$$\frac{{\rm{\partial }}}{{\rm{\partial }}t}\rho ({\boldsymbol{x}})=-\,{\rm{\nabla }}\cdot [\rho ({\boldsymbol{x}})\cdot (\overrightarrow{{\boldsymbol{v}}}({\boldsymbol{x}})+\overrightarrow{{\boldsymbol{u}}}({\boldsymbol{x}}))]+\mathop{\sum }\limits_{i,j=1}^{N}\frac{{{\rm{\partial }}}^{2}}{{\rm{\partial }}{{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{i}{\rm{\partial }}{{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{j}}[{D}_{i,j}({\boldsymbol{x}})\rho ({\boldsymbol{x}})]$$

For the notation: \(\nabla \cdot \) is the divergence operator; \(\rho ({\boldsymbol{x}})\) is the density of tissues at location \({\boldsymbol{x}}\) in the state-space; \(\overrightarrow{{\boldsymbol{v}}}({\boldsymbol{x}})+\overrightarrow{{\boldsymbol{u}}}({\boldsymbol{x}})\) is the velocity of a neighbourhood in the state-space; \(\overrightarrow{{\boldsymbol{v}}}({\boldsymbol{x}})\) is the division minus the death rate field, estimated from data; \(\overrightarrow{{\boldsymbol{u}}}({\boldsymbol{x}})\) is the velocity field due to unmodelled terms such as cell migration (will be estimated now); and \(D({\boldsymbol{x}})\) is the diffusion coefficient matrix. We assumed that fluctuations are proportional to the number of cells (for example, changes in nutrient availability modify growth rates of existing cells, rather than adding or removing cells at a constant rate).

Formally, \(dX=[{\boldsymbol{v}}({\boldsymbol{x}})+{\boldsymbol{u}}({\boldsymbol{x}})]dt+{\sigma }({\boldsymbol{x}})\,\circ \,d{W}_{t}\). Where \(d{W}_{t}\) is an N-dimensional Brownian motion and \({\sigma }({\boldsymbol{x}})={\sigma }\cdot {({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{1},\ldots ,{{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{N})}^{T}\) multiplies each component independently. Overall, for \(i\ne j\) \({D}_{i,j}({\boldsymbol{x}})=0\) and for \(i=j\) \({D}_{i,i}({\boldsymbol{x}})={{\sigma }}^{2}{{{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{i}}^{2}\). The diffusion term becomes: \({{\sigma }}^{2}{\sum }_{i=1}^{N}\frac{{{\rm{\partial }}}^{{\bf{2}}}}{{{\rm{\partial }}}^{2}{{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{i}}[{{{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{i}}^{2}\rho ({\boldsymbol{x}})]\). We henceforth denote the scalar \({\sum }_{i=1}^{N}\frac{{{\rm{\partial }}}^{2}}{{{\rm{\partial }}}^{2}{{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{i}}[{{{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{i}}^{2}\rho ({\boldsymbol{x}})]\) as \(D({\boldsymbol{x}})\). The equation becomes:

$$\frac{{\rm{\partial }}}{{\rm{\partial }}t}\rho (x)=-\,{\rm{\nabla }}\cdot [\rho ({\boldsymbol{x}})\cdot \overrightarrow{{\boldsymbol{v}}}({\boldsymbol{x}})]-{\rm{\nabla }}\cdot [\rho ({\boldsymbol{x}})\cdot \overrightarrow{{\boldsymbol{u}}}({\boldsymbol{x}})]+{{\sigma }}^{{\bf{2}}}D({\boldsymbol{x}})$$

For a large sample of patients, we can assume that sampling the same tumours within a number of days would produce approximately the same distribution. This implies that \(\frac{\partial \rho }{\partial t}\approx 0\). Thus:

$${\rm{\nabla }}\cdot \,[\rho ({\boldsymbol{x}})\cdot \overrightarrow{{\boldsymbol{v}}}({\boldsymbol{x}})]=-\,{\rm{\nabla }}\cdot [\rho ({\boldsymbol{x}})\cdot \overrightarrow{{\boldsymbol{u}}}({\boldsymbol{x}})]+{{\sigma }}^{2}D({\boldsymbol{x}})$$

The left-hand side is inferred from data for all \({\boldsymbol{x}}\). Recall, \(\overrightarrow{{\boldsymbol{v}}}({\boldsymbol{x}})\) is estimated from division markers and we estimated \(\rho (x)\) by computing the location of tissue of each patient in the state-space followed by kernel density estimation. We then numerically evaluated the divergence \({\rm{\nabla }}\cdot (\rho ({\boldsymbol{x}})\cdot \overrightarrow{{\boldsymbol{v}}}({\boldsymbol{x}}))\) using finite differences.

By plotting \({\rm{\nabla }}\cdot (\rho \cdot \overrightarrow{{\boldsymbol{v}}})\), we can visualize the net contribution (in units of change in density per unit time) of the missing terms. In the special case where \(\sigma \approx 0\), we directly obtained the divergence of the error (for example, migration) field as \({\rm{\nabla }}\cdot (\rho \cdot \overrightarrow{{\boldsymbol{u}}})=-\,{\rm{\nabla }}\cdot (\rho \cdot \overrightarrow{{\boldsymbol{v}}})\). Plotting \({\rm{\nabla }}\cdot (\rho \cdot \overrightarrow{{\boldsymbol{v}}})\) thus identified the sources and sinks of the error field, as well as the magnitude of error. Note, for interpretability, we divided the rates by the maximal \(\rho \) so that units are in [fractions of maximal density/∆t].

To quantify the contribution of diffusion versus deterministic terms (migration, and so on) we solved an ordinary least squares problem with a single parameter \(\sigma \):

$$\hat{{\sigma }}=\mathop{\text{arg min}}\limits_{{\sigma }}\sum _{x}({\rm{\nabla }}\cdot (\rho ({\boldsymbol{x}})\cdot \overrightarrow{{\boldsymbol{v}}}({\boldsymbol{x}}))-{{\sigma }}^{2}D{({\boldsymbol{x}}))}^{2}$$

The variable \({\boldsymbol{x}}\) is taken over a discrete 2D grid. Solving for \(\sigma \) this way implies that the deterministic error velocity \(\overrightarrow{{\boldsymbol{u}}}({\boldsymbol{x}})\) should not include components that could be explained by stochastic diffusion.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.