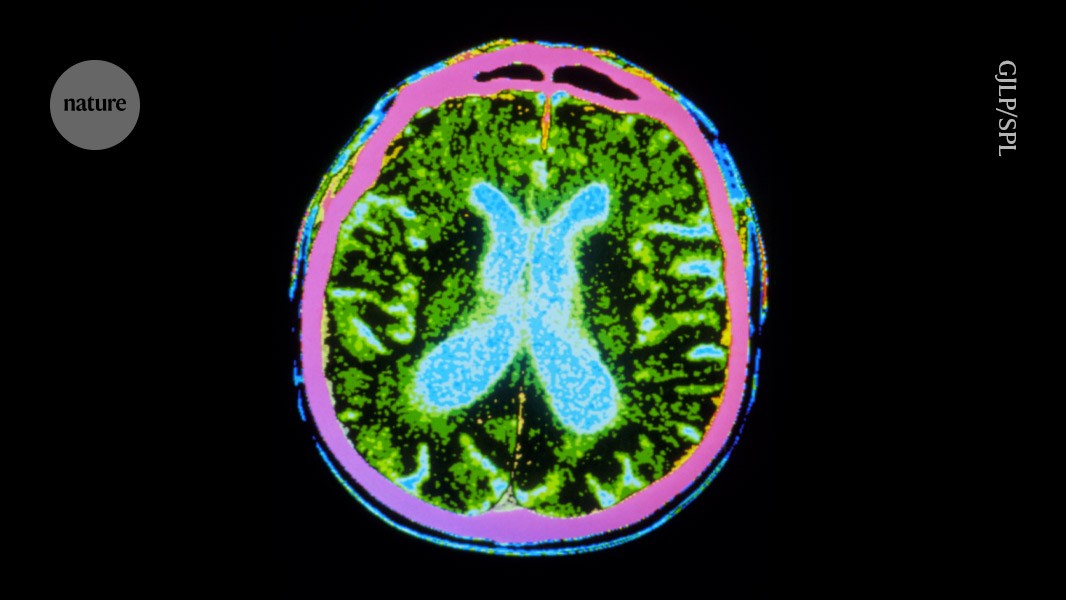

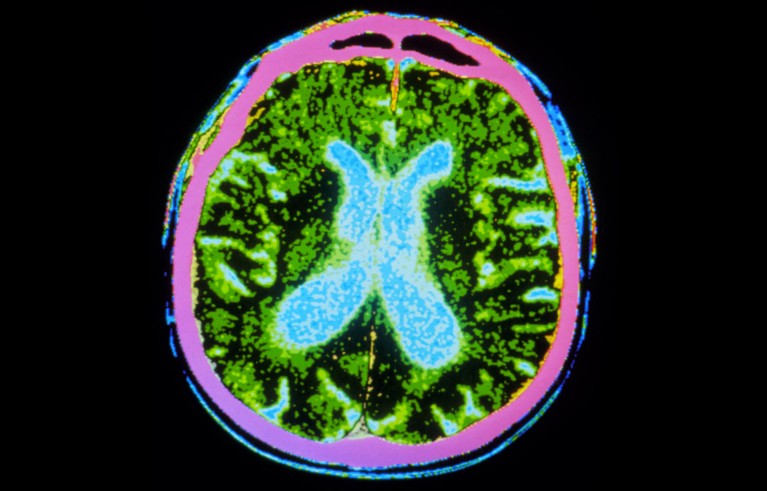

Millions of stem cells were injected into the brains of people with Parkinson’s disease, as part of a safety trial.Credit: GJLP/Science Photo Library

Two hotly anticipated clinical trials using stem cells to treat people with Parkinson’s disease have published encouraging results. The early-stage trials demonstrate that injecting stem-cell-derived neurons into the brain is safe1,2. They also show hints of benefit: the transplanted cells can replace the dopamine-producing cells that die off in people with the disease, and survive long enough to produce the crucial hormone. Some participants experienced visible reductions in tremors.

The studies, published by two groups in Nature today, are “a big leap in the field”, says Malin Parmar, a stem-cell biologist at Lund University, Sweden. “These cell products are safe and show signs of cell survival.”

Japan’s big bet on stem-cell therapies might soon pay off with breakthrough therapies

The trials were mainly designed to test safety and were small, involving 19 individuals in total, which is not enough to indicate whether the intervention is effective, says Parmar.

“Some people got slightly better and others didn’t get worse,” says Jeanne Loring, a stem-cell researcher at Scripps Research in La Jolla, California. This could be due to the relatively small number of cells transplanted in these first early-stage trials.

Parkinson’s is a progressive neurological condition driven by the loss of dopamine-producing neurons, which causes tremors, stiffness and slowness in movement. There is currently no cure for the condition, which is projected to affect 25 million people globally by 2050.

Cell therapies are designed to replace damaged neurons, but previous trials using fetal tissue transplants have had mixed results. The latest findings are the first among a handful of global trials testing more-advanced cell therapies.

Cell shots

The larger of the two trials took place in the United States and Canada, involving 9 men and 3 women with Parkinson’s disease, with a median age of 671. The researchers coaxed stem cells from donated human embryos into neural progenitor cells and froze them for safekeeping.

Just before surgery, the cells were thawed and injected into a walnut-shaped, deep-brain structure called the putamen, which is an important motor-relay station. Neurons that die in Parkinson’s disease extend their tentacles out to the putamen.

The stem cells were injected to 18 sites across the putamen in both hemispheres — “to roughly fill up that region of the brain”, says Viviane Tabar, a neurosurgeon at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City who conducted the US surgeries.

Five individuals received a dose of 0.9 million cells and 7 received 2.7 million cells, in the hope that 100,000 and 300,000 cells, respectively, would survive the surgery. A healthy brain typically has 300,000 dopamine-producing neurons. The recipients were given immune-suppressing drugs for one year after the surgery to prevent their bodies from rejecting the transplant.

Brain scans showed an overall increase in dopamine production, suggesting that some neurons survived the entire 18-month observation period, even after the participants stopped receiving immune-suppressing drugs.

On average, individuals who received the low dose showed a 9-point improvement in their symptoms on a standardized assessment for Parkinson’s disease, and those who received the high dose gained 23 points. The assessment measures individuals’ daily life activities, pain levels, sleep and eating. Agnete Kirkeby, a stem-cell scientist at the University of Copenhagen who is involved in a European trial, points out that this metric is subjective and can be influenced by the placebo effect, but says the results warrant larger trials.

Fewer tremors

The second study2, conducted in Japan, started with adult cells from a donor and reverted them to a pluripotent state, from which they could be coaxed into becoming neural progenitor cells. Freshly differentiated cells were immediately injected into participants, comprising four men and three women aged 50–69.

Three individuals received up to 5 million cells and 4 received up to 11 million cells, of which 150,000 and 300,000 cells, respectively, were expected to survive. “This low survival rate is a big problem that needs to be solved,” says Jun Takahashi, a neurosurgeon at Kyoto University in Japan, who led the trial. Participants were given immune-suppressing drugs for 15 months.