You have full access to this article via your institution.

People who earn a living in the fossil-fuel industry (such as on this pipe-laying vessel in China) will need support during the energy transition.Credit: Zhang Wujun/VCG/Getty

In the mid-1990s, when world leaders began to develop the first plans to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases, the path forwards was hardly clear. A lot of energy had gone into negotiating the Kyoto Protocol at the third climate conference (COP3) in Japan, resulting in the world’s first legally binding agreement to cut climate-warming gases. Much less time was given to discussing precisely how high-income countries could achieve the agreed emissions reductions by 2012 — requiring an average cut of 5.2% from nations’ 1990 levels.

Can we still escape catastrophic climate change? The hopes and hurdles in seven charts

You could argue it is the opposite today. Almost three decades later, it seems that countries lack the will or the foresight of previous generations to agree on the cuts necessary to avoid dangerous climate change. And yet, despite the political headwinds, the long-hoped-for energy transition is now well under way, as we report in a News feature (see go.nature.com/4quit62). Prices of renewable technologies are plummeting and technological breakthroughs in battery storage have ushered in a clean-energy revolution.

That said, the current speed at which countries are changing from fossil fuels to renewables is not yet sufficient to rein in dangerous climate change. Average temperatures are still projected to rise to nearly 3 °C above pre-industrial levels by 2100. Such warming will result in further harmful heat waves, extreme rainfall and droughts, melting of ice sheets, sea ice and glaciers, heating of the ocean and rising sea levels, says the World Meteorological Organization (see go.nature.com/45yqkzh). Such effects might be tempered if governments could take just one action: divert fossil-fuel subsidies to more-deserving causes.

Governments worldwide are paying at least US$1 trillion annually in subsidies for fossil fuels, according to an article in Our World in Data (see go.nature.com/4a43xys). However, the International Monetary Fund thinks the figure is closer to $7 trillion. Such funds are explicitly designed to keep fossil-fuel prices low. By contrast, the G20 group of the world’s richest economies paid out only $168 billion in subsidies for renewable power, finds a 2024 estimate by the International Institute for Sustainable Development (see go.nature.com/46tip6k).

What happened at COP30? 4 science take-homes from the climate summit

To give some indication of the scale of the transition already achieved: last year, the total amount of wind and solar power generated exceeded that produced by coal, which was, for roughly a century, the world’s main source of electricity. Moreover, whereas production of coal-derived power is projected to remain constant at around 11,000 terawatt-hours annually, the amount of solar and wind power produced will keep increasing and is estimated to reach 12,000 terawatt-hours this year.

The costs of these renewable technologies have fallen to the point that constructing and running conventional fossil-fuel power plants is uncompetitive by comparison. The United States is one of several countries where it can be cheaper to install clean-energy technologies than it is to continue purchasing coal to keep existing power plants running. And yet, even there, subsidies for fossil fuels (nearly $40 billion last year) are showing no signs of abating.

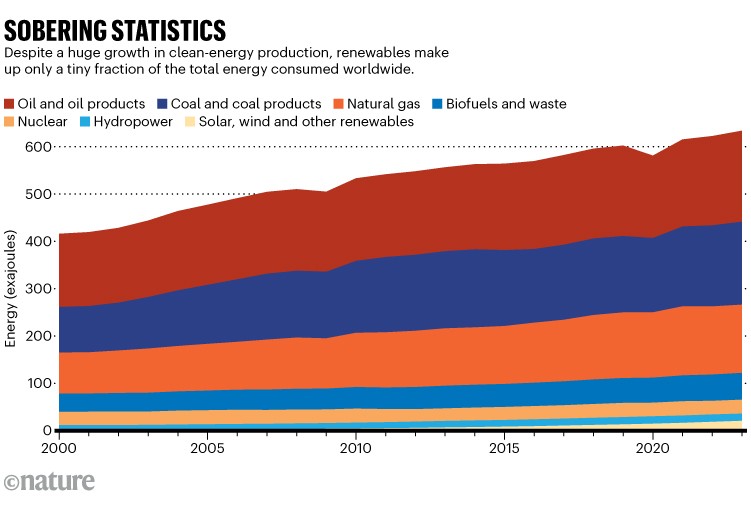

These subsidies might be one reason why solar and wind sources still make up a relatively small fraction of the total energy consumed by households and industries (see ‘Sobering statistics’). Energy consumed is a measure distinct from just power production. Some 80% of all energy consumed comes from coal, oil and natural gas and their consumption continues to increase. It is this dependence on fossil-fuel-derived energy that is boosting greenhouse-gas emissions — at a time when such emissions need to be coming down.

Source: IEA World Energy Outlook 2024

As we have argued previously, the climate transition must be a just one (see Nature 629, 8; 2024). It has to take into account the needs of less-industrialized economies and those of people everywhere who depend on fossil-fuel industries to support their families. Subsidies cannot be phased out instantly, but they can be used instead to protect the people whose lives and livelihoods will be affected by the clean-energy transition. That is a much better application of such investments.

Renewables’ falling costs mean that there are fewer reasons why countries cannot make faster progress on limiting climate change by rolling out existing clean-energy technologies more quickly. And diverting the subsidies creates an opportunity: the money that currently goes to coal, gas and oil producers can instead be used to support all those who stand to be negatively affected by the energy transition.